Hinduism

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Hinduism is the world’s third largest religion. It is an Indian religion and dharma, or way of life,[note 1] widely practised in the Indian subcontinent and parts of Southeast Asia. Hinduism has been called the oldest religion in the world,[note 2] and some practitioners and scholars refer to it as Sanātana Dharma, “the eternal tradition”, or the “eternal way”, beyond human history.[4][5] Scholars regard Hinduism as a fusion[note 3] or synthesis[6][note 4] of various Indian cultures and traditions,[7][note 5] with diverse roots[8][note 6] and no founder.[9] This “Hindu synthesis” started to develop between 500 BCE and 300 CE,[10] after the end of the Vedic period (1500 to 500 BCE),[10][11] and flourished in the medieval period, with the decline of Buddhism in India.[12]

Although Hinduism contains a broad range of philosophies, it is linked by shared concepts, recognisable rituals, cosmology, shared textual resources, and pilgrimage to sacred sites. Hindu texts are classified into Śruti (“heard”) and Smṛti (“remembered”). These texts discuss theology, philosophy, mythology, Vedic yajna, Yoga, agamic rituals, and temple building, among other topics.[13] Major scriptures include the Vedas and the Upanishads, the Puranas, the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, and the Āgamas.[14][15] Sources of authority and eternal truths in its texts play an important role, but there is also a strong Hindu tradition of questioning authority in order to deepen the understanding of these truths and to further develop the tradition.[16]

Prominent themes in Hindu beliefs include the four Puruṣārthas, the proper goals or aims of human life, namely Dharma (ethics/duties), Artha (prosperity/work), Kama (desires/passions) and Moksha (liberation/freedom from the cycle of death and rebirth/salvation);[17][18] karma (action, intent and consequences), Saṃsāra (cycle of death and rebirth), and the various Yogas (paths or practices to attain moksha).[15][19] Hindu practices include rituals such as puja (worship) and recitations, japa, meditation, family-oriented rites of passage, annual festivals, and occasional pilgrimages. Some Hindus leave their social world and material possessions, then engage in lifelong Sannyasa (monastic practices) to achieve Moksha.[20] Hinduism prescribes the eternal duties, such as honesty, refraining from injuring living beings (ahimsa), patience, forbearance, self-restraint, and compassion, among others.[web 1][21] The four largest denominations of Hinduism are the Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism and Smartism.[22]

Hinduism is the world’s third largest religion; its followers, known as Hindus, constitute about 1.15 billion, or 15–16% of the global population.[web 2][23] Hinduism is the most widely professed faith in India, Nepal and Mauritius. It is also the predominant religion in Bali, Indonesia.[24] Significant numbers of Hindu communities are also found in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, North America, Europe, Oceania, Africa, and other countries.[25][26]

Etymology

The word Hindū is derived from Indo-Aryan[27]/Sanskrit[28] root Sindhu.[28][29] The Proto-Iranian sound change *s > h occurred between 850–600 BCE, according to Asko Parpola.[citation needed]

The use of the term Hinduism to describe a collection of practices and beliefs is a recent European construction, the term “Hindu” was coined in position to other religions and used to describe those that were not of the other religions. Before the British began to categorise communities strictly by religion, Indians generally did not define themselves exclusively through their religious beliefs; identities were segmented on the basis of locality, language, caste, occupation and sect.[30][page needed]

It is believed that Hindu was used as the name for the Indus River in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent (modern day Pakistan and Northern India).[28][note 7] According to Gavin Flood, “The actual term Hindu first occurs as a Persian geographical term for the people who lived beyond the river Indus (Sanskrit: Sindhu)”,[28] more specifically in the 6th-century BCE inscription of Darius I (550–486 BCE).[31] The term Hindu in these ancient records is a geographical term and did not refer to a religion.[28] Among the earliest known records of ‘Hindu’ with connotations of religion may be in the 7th-century CE Chinese text Record of the Western Regions by Xuanzang,[31] and 14th-century Persian text Futuhu’s-salatin by ‘Abd al-Malik Isami.[note 8]

Thapar states that the word Hindu is found as heptahindu in Avesta – equivalent to Rigvedic sapta sindhu, while hndstn (pronounced Hindustan) is found in a Sasanian inscription from the 3rd century CE, both of which refer to parts of northwestern South Asia.[38] The Arabic term al-Hind referred to the people who live across the River Indus.[39] This Arabic term was itself taken from the pre-Islamic Persian term Hindū, which refers to all Indians. By the 13th century, Hindustan emerged as a popular alternative name of India, meaning the “land of Hindus”.[40][note 9]

The term Hindu was later used occasionally in some Sanskrit texts such as the later Rajataranginis of Kashmir (Hinduka, c. 1450) and some 16th- to 18th-century Bengali Gaudiya Vaishnava texts including Chaitanya Charitamrita and Chaitanya Bhagavata. These texts used it to distinguish Hindus from Muslims who are called Yavanas (foreigners) or Mlecchas (barbarians), with the 16th-century Chaitanya Charitamrita text and the 17th-century Bhakta Mala text using the phrase “Hindu dharma“.[41] It was only towards the end of the 18th century that European merchants and colonists began to refer to the followers of Indian religions collectively as Hindus.

The term Hinduism, then spelled Hindooism, was introduced into the English language in the 18th century to denote the religious, philosophical, and cultural traditions native to India.[42]

Definitions

Hinduism includes a diversity of ideas on spirituality and traditions, but has no ecclesiastical order, no unquestionable religious authorities, no governing body, no prophet(s) nor any binding holy book; Hindus can choose to be polytheistic, pantheistic, panentheistic, pandeistic, henotheistic, monotheistic, monistic, agnostic, atheistic or humanist.[43][44][45] Ideas about all the major issues of faith and lifestyle including: vegetarianism, nonviolence, belief in rebirth, even caste, are subjects of debate, not dogma.[30][page needed]

Because of the wide range of traditions and ideas covered by the term Hinduism, arriving at a comprehensive definition is difficult.[28] The religion “defies our desire to define and categorize it”.[46] Hinduism has been variously defined as a religion, a religious tradition, a set of religious beliefs, and “a way of life”.[47][note 1] From a Western lexical standpoint, Hinduism like other faiths is appropriately referred to as a religion. In India the term dharma is preferred, which is broader than the Western term religion.

The study of India and its cultures and religions, and the definition of “Hinduism”, has been shaped by the interests of colonialism and by Western notions of religion.[48] Since the 1990s, those influences and its outcomes have been the topic of debate among scholars of Hinduism,[49][note 10] and have also been taken over by critics of the Western view on India.[50][note 11]

Typology

AUM, a stylised letter of Devanagari script, used as a religious symbol in Hinduism

Hinduism as it is commonly known can be subdivided into a number of major currents. Of the historical division into six darsanas (philosophies), two schools, Vedanta and Yoga, are currently the most prominent.[51] Classified by primary deity or deities, four major Hinduism modern currents are Vaishnavism (Vishnu), Shaivism (Shiva), Shaktism (Devi) and Smartism (five deities treated as same).[52][53] Hinduism also accepts numerous divine beings, with many Hindus considering the deities to be aspects or manifestations of a single impersonal absolute or ultimate reality or God, while some Hindus maintain that a specific deity represents the supreme and various deities are lower manifestations of this supreme.[54] Other notable characteristics include a belief in existence of ātman (soul, self), reincarnation of one’s ātman, and karma as well as a belief in dharma (duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and right way of living).

McDaniel (2007) classifies Hinduism into six major kinds and numerous minor kinds, in order to understand expression of emotions among the Hindus.[55] The major kinds, according to McDaniel are, Folk Hinduism, based on local traditions and cults of local deities and is the oldest, non-literate system; Vedic Hinduism based on the earliest layers of the Vedas traceable to 2nd millennium BCE; Vedantic Hinduism based on the philosophy of the Upanishads, including Advaita Vedanta, emphasizing knowledge and wisdom; Yogic Hinduism, following the text of Yoga Sutras of Patanjali emphasizing introspective awareness; Dharmic Hinduism or “daily morality”, which McDaniel states is stereotyped in some books as the “only form of Hindu religion with a belief in karma, cows and caste”; and Bhakti or devotional Hinduism, where intense emotions are elaborately incorporated in the pursuit of the spiritual.[55]

Michaels distinguishes three Hindu religions and four forms of Hindu religiosity.[56] The three Hindu religions are “Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism”, “folk religions and tribal religions”, and “founded religions.[57] The four forms of Hindu religiosity are the classical “karma-marga”,[58] jnana-marga,[59] bhakti-marga,[59] and “heroism”, which is rooted in militaristic traditions, such as Ramaism and parts of political Hinduism.[58] This is also called virya-marga.[59] According to Michaels, one out of nine Hindu belongs by birth to one or both of the Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism and Folk religion typology, whether practicing or non-practicing. He classifies most Hindus as belonging by choice to one of the “founded religions” such as Vaishnavism and Shaivism that are salvation-focussed and often de-emphasize Brahman priestly authority yet incorporate ritual grammar of Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism.[60] He includes among “founded religions” Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism that are now distinct religions, syncretic movements such as Brahmo Samaj and the Theosophical Society, as well as various “Guru-isms” and new religious movements such as Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and ISKCON.[61]

Inden states that the attempt to classify Hinduism by typology started in the imperial times, when proselytizing missionaries and colonial officials sought to understand and portray Hinduism from their interests.[62] Hinduism was construed as emanating not from a reason of spirit but fantasy and creative imagination, not conceptual but symbolical, not ethical but emotive, not rational or spiritual but of cognitive mysticism. This stereotype followed and fit, states Inden, with the imperial imperatives of the era, providing the moral justification for the colonial project.[62] From tribal Animism to Buddhism, everything was subsumed as part of Hinduism. The early reports set the tradition and scholarly premises for typology of Hinduism, as well as the major assumptions and flawed presuppositions that has been at the foundation of Indology. Hinduism, according to Inden, has been neither what imperial religionists stereotyped it to be, nor is it appropriate to equate Hinduism to be merely monist pantheism and philosophical idealism of Advaita Vedanta.[62]

Indigenous understanding

Sanātana Dharma

To its adherents, Hinduism is a traditional way of life.[63] Many practitioners refer to the “orthodox” form of Hinduism as Sanātana Dharma, “the eternal law” or the “eternal way”.[64][65] The Sanskrit word dharma has a much broader meaning than religion and is not its equivalent. All aspects of a Hindu life, namely acquiring wealth (artha), fulfillment of desires (kama), and attaining liberation (moksha), are part of dharma, which encapsulates the “right way of living” and eternal harmonious principles in their fulfillment.[66][67]

According to the editors of the Encyclopædia Britannica, Sanātana Dharma historically referred to the “eternal” duties religiously ordained in Hinduism, duties such as honesty, refraining from injuring living beings (ahimsa), purity, goodwill, mercy, patience, forbearance, self-restraint, generosity, and asceticism. These duties applied regardless of a Hindu’s class, caste, or sect, and they contrasted with svadharma, one’s “own duty”, in accordance with one’s class or caste (varna) and stage in life (puruṣārtha).[web 1] In recent years, the term has been used by Hindu leaders, reformers, and nationalists to refer to Hinduism. Sanatana dharma has become a synonym for the “eternal” truth and teachings of Hinduism, that transcend history and are “unchanging, indivisible and ultimately nonsectarian”.[web 1]

According to other scholars such as Kim Knott and Brian Hatcher, Sanātana Dharma refers to “timeless, eternal set of truths” and this is how Hindus view the origins of their religion. It is viewed as those eternal truths and tradition with origins beyond human history, truths divinely revealed (Shruti) in the Vedas – the most ancient of the world’s scriptures.[68][69] To many Hindus, the Western term “religion” to the extent it means “dogma and an institution traceable to a single founder” is inappropriate for their tradition, states Hatcher. Hinduism, to them, is a tradition that can be traced at least to the ancient Vedic era.[69][70][note 12]

Vaidika dharma

Some have referred to Hinduism as the Vaidika dharma.[72] The word ‘Vaidika’ in Sanskrit means ‘derived from or conformable to the Veda’ or ‘relating to the Veda’.[73] Traditional scholars employed the terms Vaidika and Avaidika, those who accept the Vedas as a source of authoritative knowledge and those who do not, to differentiate various Indian schools from Jainism, Buddhism and Charvaka. According to Klaus Klostermaier, the term Vaidika dharma is the earliest self-designation of Hinduism.[74][75] According to Arvind Sharma, the historical evidence suggests that “the Hindus were referring to their religion by the term vaidika dharma or a variant thereof” by the 4th-century CE.[76] According to Brian K. Smith “[i]t is ‘debatable at the very least’ as to whether the term Vaidika Dharma cannot, with the proper concessions to historical, cultural and ideological specificity, be comparable to and translated as ‘Hinduism’ or ‘Hindu religion’.”[77]

According to Alexis Sanderson, the early Sanskrit texts differentiate between Vaidika, Vaishnava, Shaiva, Shakta, Saura, Buddhist and Jaina traditions. However, the late 1st-millennium CE Indic consensus had “indeed come to conceptualize a complex entity corresponding to Hinduism as opposed to Buddhism and Jainism excluding only certain forms of antinomian Shakta-Shaiva” from its fold.[78] Some in the Mimamsa school of Hindu philosophy considered the Agamas such as the Pancaratrika to be invalid because it did not conform to the Vedas. Some Kashmiri scholars rejected the esoteric tantric traditions to be a part of Vaidika dharma.[78][79] The Atimarga Shaivism ascetic tradition, datable to about 500 CE, challenged the Vaidika frame and insisted that their Agamas and practices were not only valid, they were superior than those of the Vaidikas.[80] However, adds Sanderson, this Shaiva ascetic tradition viewed themselves as being genuinely true to the Vedic tradition and “held unanimously that the Śruti and Smṛti of Brahmanism are universally and uniquely valid in their own sphere, […] and that as such they [Vedas] are man’s sole means of valid knowledge […]”.[80]

The term Vaidika dharma means a code of practice that is “based on the Vedas”, but it is unclear what “based on the Vedas” really implies, states Julius Lipner.[70] The Vaidika dharma or “Vedic way of life”, states Lipner, does not mean “Hinduism is necessarily religious” or that Hindus have a universally accepted “conventional or institutional meaning” for that term.[70] To many, it is as much a cultural term. Many Hindus do not have a copy of the Vedas nor have they ever seen or personally read parts of a Veda, like a Christian might relate to the Bible or a Muslim might to the Quran. Yet, states Lipner, “this does not mean that their [Hindus] whole life’s orientation cannot be traced to the Vedas or that it does not in some way derive from it”.[70]

Many religious Hindus implicitly acknowledge the authority of the Vedas, this acknowledgment is often “no more than a declaration that someone considers himself [or herself] a Hindu.” Some Hindus challenge the authority of the Vedas, thereby implicitly acknowledging its importance to the history of Hinduism, states Lipner.[70]

Hindu modernism

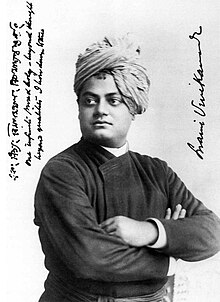

Swami Vivekananda was a key figure in introducing Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and the United States,[81] raising interfaith awareness and making Hinduism a world religion.[82]

Beginning in the 19th century, Indian modernists re-asserted Hinduism as a major asset of Indian civilisation,[83] meanwhile “purifying” Hinduism from its Tantric elements[84] and elevating the Vedic elements. Western stereotypes were reversed, emphasizing the universal aspects, and introducing modern approaches of social problems.[83] This approach had a great appeal, not only in India, but also in the west.[83] Major representatives of “Hindu modernism”[85] are Raja Rammohan Roy, Vivekananda, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Mahatma Gandhi.[86]

Raja Rammohan Roy is known as the father of the Hindu Renaissance.[87] He was a major influence on Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902), who, according to Flood, was “a figure of great importance in the development of a modern Hindu self-understanding and in formulating the West’s view of Hinduism”.[88] Central to his philosophy is the idea that the divine exists in all beings, that all human beings can achieve union with this “innate divinity”,[85] and that seeing this divine as the essence of others will further love and social harmony.[85] According to Vivekananda, there is an essential unity to Hinduism, which underlies the diversity of its many forms.[85] According to Flood, Vivekananda’s vision of Hinduism “is one generally accepted by most English-speaking middle-class Hindus today”.[89] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan sought to reconcile western rationalism with Hinduism, “presenting Hinduism as an essentially rationalistic and humanistic religious experience”.[90]

This “Global Hinduism”[91] has a worldwide appeal, transcending national boundaries[91] and, according to Flood, “becoming a world religion alongside Christianity, Islam and Buddhism”,[91] both for the Hindu diaspora communities and for westerners who are attracted to non-western cultures and religions.[91] It emphasizes universal spiritual values such as social justice, peace and “the spiritual transformation of humanity”.[91] It has developed partly due to “re-enculturation”,[92] or the Pizza effect,[92] in which elements of Hindu culture have been exported to the West, gaining popularity there, and as a consequence also gained greater popularity in India.[92] This globalization of Hindu culture brought “to the West teachings which have become an important cultural force in western societies, and which in turn have become an important cultural force in India, their place of origin”.[93]

Legal Definitions

The definition of Hinduism in Indian Law is: “Acceptance of the Vedas with reverence; recognition of the fact that the means or ways to salvation are diverse; and realization of the truth that the number of gods to be worshipped is large”[94][30][page needed]

Western understanding

The term Hinduism is coined in Western ethnography in the 18th century,[42][95] and refers to the fusion[note 3] or synthesis[note 4][6] of various Indian cultures and traditions.[7][note 5] which emerged after the Vedic period, between 500[10]–200[11] BCE and c. 300 CE,[10] the beginning of the “Epic and Puranic” c.q. “Preclassical” period.[10][11]

Hinduism’s tolerance to variations in belief and its broad range of traditions make it difficult to define as a religion according to traditional Western conceptions.[98]

Some academics suggest that Hinduism can be seen as a category with “fuzzy edges” rather than as a well-defined and rigid entity. Some forms of religious expression are central to Hinduism and others, while not as central, still remain within the category. Based on this idea Ferro-Luzzi has developed a ‘Prototype Theory approach’ to the definition of Hinduism.[99]

Diversity and unity

Diversity

Ganesha is one of the best-known and most worshipped deities in the Hindu pantheon

Hinduism has been described as a tradition having a “complex, organic, multileveled and sometimes internally inconsistent nature”.[100] Hinduism does not have a “unified system of belief encoded in a declaration of faith or a creed“,[28] but is rather an umbrella term comprising the plurality of religious phenomena of India.[101] According to the Supreme Court of India,

Unlike other religions in the World, the Hindu religion does not claim any one Prophet, it does not worship any one God, it does not believe in any one philosophic concept, it does not follow any one act of religious rites or performances; in fact, it does not satisfy the traditional features of a religion or creed. It is a way of life and nothing more”.[102]

Part of the problem with a single definition of the term Hinduism is the fact that Hinduism does not have a founder.[103] It is a synthesis of various traditions,[104] the “Brahmanical orthopraxy, the renouncer traditions and popular or local traditions”.[96]

Theism is also difficult to use as a unifying doctrine for Hinduism, because while some Hindu philosophies postulate a theistic ontology of creation, other Hindus are or have been atheists.[citation needed]

Sense of unity

Despite the differences, there is also a sense of unity.[105] Most Hindu traditions revere a body of religious or sacred literature, the Vedas,[106] although there are exceptions.[107] These texts are a reminder of the ancient cultural heritage and point of pride for Hindus,[108][109] with Louis Renou stating that “even in the most orthodox domains, the reverence to the Vedas has come to be a simple raising of the hat”.[108][110]

Halbfass states that, although Shaivism and Vaishaism may be regarded as “self-contained religious constellations”,[105] there is a degree of interaction and reference between the “theoreticians and literary representatives”[105] of each tradition that indicates the presence of “a wider sense of identity, a sense of coherence in a shared context and of inclusion in a common framework and horizon”.[105]

Indigenous developments

The notion of common denominators for several religions and traditions of India further developed from the 12th century CE on.[111] Lorenzen traces the emergence of a “family resemblance”, and what he calls as “beginnings of medieval and modern Hinduism” taking shape, at c. 300 – 600 CE, with the development of the early Puranas, and continuities with the earlier Vedic religion.[112] Lorenzen states that the establishment of a Hindu self-identity took place “through a process of mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim Other”.[113] According to Lorenzen, this “presence of the Other”[113] is necessary to recognise the “loose family resemblance” among the various traditions and schools,[114]

According to the Indologist Alexis Sanderson, before Islam arrived in India, the “Sanskrit sources differentiated Vaidika, Vaiṣṇava, Śaiva, Śākta, Saura, Buddhist, and Jaina traditions, but they had no name that denotes the first five of these as a collective entity over and against Buddhism and Jainism.” This absence of a formal name, states Sanderson, does not mean that the corresponding concept of Hinduism did not exist. By late 1st-millennium CE, the concept of a belief and tradition distinct from Buddhism and Jainism had emerged.[115] This complex tradition accepted in its identity almost all of what is currently Hinduism, except certain antinomian tantric movements.[115] Some conservative thinkers of those times questioned whether certain Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta texts or practices were consistent with the Vedas, or were invalid in their entirety. Moderates then, and most orthoprax scholars later, agreed that though there are some variations, the foundation of their beliefs, the ritual grammar, the spiritual premises and the soteriologies were same. “This sense of greater unity”, states Sanderson, “came to be called Hinduism”.[115]

According to Nicholson, already between the 12th and the 16th centuries “certain thinkers began to treat as a single whole the diverse philosophical teachings of the Upanishads, epics, Puranas, and the schools known retrospectively as the ‘six systems’ (saddarsana) of mainstream Hindu philosophy.”[116] The tendency of “a blurring of philosophical distinctions” has also been noted by Burley.[117] Hacker called this “inclusivism”[106] and Michaels speaks of “the identificatory habit”.[13] Lorenzen locates the origins of a distinct Hindu identity in the interaction between Muslims and Hindus,[118] and a process of “mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim other”,[119][note 13] which started well before 1800.[120] Michaels notes:

As a counteraction to Islamic supremacy and as part of the continuing process of regionalization, two religious innovations developed in the Hindu religions: the formation of sects and a historicization which preceded later nationalism […] [S]aints and sometimes militant sect leaders, such as the Marathi poet Tukaram (1609–1649) and Ramdas (1608–1681), articulated ideas in which they glorified Hinduism and the past. The Brahmins also produced increasingly historical texts, especially eulogies and chronicles of sacred sites (Mahatmyas), or developed a reflexive passion for collecting and compiling extensive collections of quotations on various subjects.[121]

This inclusivism[122] was further developed in the 19th and 20th centuries by Hindu reform movements and Neo-Vedanta,[123] and has become characteristic of modern Hinduism.[106]

Colonial influences

The notion and reports on “Hinduism” as a “single world religious tradition”[124] was popularised by 19th-century proselytizing missionaries and European Indologists, roles sometimes served by the same person, who relied on texts preserved by Brahmins (priests) for their information of Indian religions, and animist observations that the missionary Orientalists presumed was Hinduism.[124][62][125] These reports influenced perceptions about Hinduism. Some scholars[weasel words] state that the colonial polemical reports led to fabricated stereotypes where Hinduism was mere mystic paganism devoted to the service of devils,[note 14] while other scholars state that the colonial constructions influenced the belief that the Vedas, Bhagavad Gita, Manusmriti and such texts were the essence of Hindu religiosity, and in the modern association of ‘Hindu doctrine’ with the schools of Vedanta (in particular Advaita Vedanta) as paradigmatic example of Hinduism’s mystical nature”.[127][note 15] Pennington, while concurring that the study of Hinduism as a world religion began in the colonial era, disagrees that Hinduism is a colonial European era invention.[134] He states that the shared theology, common ritual grammar and way of life of those who identify themselves as Hindus is traceable to ancient times.[134][note 16]

Beliefs

Prominent themes in Hindu beliefs include (but are not restricted to) Dharma (ethics/duties), Samsāra (the continuing cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth), Karma (action, intent and consequences), Moksha (liberation from samsara or liberation in this life), and the various Yogas (paths or practices).[19]

Purusharthas (objectives of human life)

Classical Hindu thought accepts four proper goals or aims of human life: Dharma, Artha, Kama and Moksha. These are known as the Puruṣārthas:[17][18]

Dharma (righteousness, ethics)

Dharma is considered the foremost goal of a human being in Hinduism.[141] The concept Dharma includes behaviors that are considered to be in accord with rta, the order that makes life and universe possible,[142] and includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and “right way of living”.[143] Hindu Dharma includes the religious duties, moral rights and duties of each individual, as well as behaviors that enable social order, right conduct, and those that are virtuous.[143] Dharma, according to Van Buitenen,[144] is that which all existing beings must accept and respect to sustain harmony and order in the world. It is, states Van Buitenen, the pursuit and execution of one’s nature and true calling, thus playing one’s role in cosmic concert.[144] The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad states it as:

Nothing is higher than Dharma. The weak overcomes the stronger by Dharma, as over a king. Truly that Dharma is the Truth (Satya); Therefore, when a man speaks the Truth, they say, “He speaks the Dharma”; and if he speaks Dharma, they say, “He speaks the Truth!” For both are one.

In the Mahabharata, Krishna defines dharma as upholding both this-worldly and other-worldly affairs. (Mbh 12.110.11). The word Sanātana means eternal, perennial, or forever; thus, Sanātana Dharma signifies that it is the dharma that has neither beginning nor end.[147]

Artha (livelihood, wealth)

Artha is objective and virtuous pursuit of wealth for livelihood, obligations and economic prosperity. It is inclusive of political life, diplomacy and material well-being. The Artha concept includes all “means of life”, activities and resources that enables one to be in a state one wants to be in, wealth, career and financial security.[148] The proper pursuit of artha is considered an important aim of human life in Hinduism.[149][150]

Kāma (sensual pleasure)

Kāma (Sanskrit, Pali; Devanagari: काम) means desire, wish, passion, longing, pleasure of the senses, the aesthetic enjoyment of life, affection, or love, with or without sexual connotations.[151][152] In Hinduism, Kama is considered an essential and healthy goal of human life when pursued without sacrificing Dharma, Artha and Moksha.[153]

Mokṣa (liberation, freedom from samsara)

Moksha (Sanskrit: मोक्ष mokṣa) or mukti (Sanskrit: मुक्ति) is the ultimate, most important goal in Hinduism. In one sense, Moksha is a concept associated with liberation from sorrow, suffering and saṃsāra (birth-rebirth cycle). A release from this eschatological cycle, in after life, particularly in theistic schools of Hinduism is called moksha.[154][155] In other schools of Hinduism, such as monistic, moksha is a goal achievable in current life, as a state of bliss through self-realization, of comprehending the nature of one’s soul, of freedom and of “realizing the whole universe as the Self”.[156][157]

Karma and samsara

Karma translates literally as action, work, or deed,[158] and also refers to a Vedic theory of “moral law of cause and effect”.[159][160] The theory is a combination of (1) causality that may be ethical or non-ethical; (2) ethicization, that is good or bad actions have consequences; and (3) rebirth.[161] Karma theory is interpreted as explaining the present circumstances of an individual with reference to his or her actions in the past. These actions and their consequences may be in a person’s current life, or, according to some schools of Hinduism, in past lives.[161][162] This cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth is called samsara. Liberation from samsara through moksha is believed to ensure lasting happiness and peace.[163][164] Hindu scriptures teach that the future is both a function of current human effort derived from free will and past human actions that set the circumstances.[165]

Moksha

The ultimate goal of life, referred to as moksha, nirvana or samadhi, is understood in several different ways: as the realization of one’s union with God; as the realization of one’s eternal relationship with God; realization of the unity of all existence; perfect unselfishness and knowledge of the Self; as the attainment of perfect mental peace; and as detachment from worldly desires. Such realization liberates one from samsara, thereby ending the cycle of rebirth, sorrow and suffering.[166][167] Due to belief in the indestructibility of the soul,[168] death is deemed insignificant with respect to the cosmic self.[169]

The meaning of moksha differs among the various Hindu schools of thought. For example, Advaita Vedanta holds that after attaining moksha a person knows their “soul, self” and identifies it as one with Brahman and everyone in all respects.[170][171] The followers of Dvaita (dualistic) schools, in moksha state, identify individual “soul, self” as distinct from Brahman but infinitesimally close, and after attaining moksha expect to spend eternity in a loka (heaven). To theistic schools of Hinduism, moksha is liberation from samsara, while for other schools such as the monistic school, moksha is possible in current life and is a psychological concept. According to Deutsche, moksha is transcendental consciousness to the latter, the perfect state of being, of self-realization, of freedom and of “realizing the whole universe as the Self”.[156][170] Moksha in these schools of Hinduism, suggests Klaus Klostermaier,[171] implies a setting free of hitherto fettered faculties, a removing of obstacles to an unrestricted life, permitting a person to be more truly a person in the full sense; the concept presumes an unused human potential of creativity, compassion and understanding which had been blocked and shut out. Moksha is more than liberation from life-rebirth cycle of suffering (samsara); Vedantic school separates this into two: jivanmukti (liberation in this life) and videhamukti (liberation after death).[172][173]

Concept of God

Hinduism is a diverse system of thought with beliefs spanning monotheism, polytheism, panentheism, pantheism, pandeism, monism, and atheism among others;[174][175][web 3] and its concept of God is complex and depends upon each individual and the tradition and philosophy followed. It is sometimes referred to as henotheistic (i.e., involving devotion to a single god while accepting the existence of others), but any such term is an overgeneralization.[176]

| “ | Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it? Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation? The gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe. Who then knows whence it has arisen? |

” |

| — Nasadiya Sukta, concerns the origin of the universe, Rig Veda, 10:129–6 [177][178][179] | ||

The Nasadiya Sukta (Creation Hymn) of the Rig Veda is one of the earliest texts[180] which “demonstrates a sense of metaphysical speculation” about what created the universe, the concept of god(s) and The One, and whether even The One knows how the universe came into being.[181][182] The Rig Veda praises various deities, none superior nor inferior, in a henotheistic manner.[183] The hymns repeatedly refer to One Truth and Reality. The “One Truth” of Vedic literature, in modern era scholarship, has been interpreted as monotheism, monism, as well as a deified Hidden Principles behind the great happenings and processes of nature.[184]

Hindus believe that all living creatures have a soul. This soul – the spirit or true “self” of every person, is called the ātman. The soul is believed to be eternal.[185] According to the monistic/pantheistic (non-dualist) theologies of Hinduism (such as Advaita Vedanta school), this Atman is indistinct from Brahman, the supreme spirit.[186] The goal of life, according to the Advaita school, is to realise that one’s soul is identical to supreme soul, that the supreme soul is present in everything and everyone, all life is interconnected and there is oneness in all life.[187][188][189] Dualistic schools (see Dvaita and Bhakti) understand Brahman as a Supreme Being separate from individual souls.[190] They worship the Supreme Being variously as Vishnu, Brahma, Shiva, or Shakti, depending upon the sect. God is called Ishvara, Bhagavan, Parameshwara, Deva or Devi, and these terms have different meanings in different schools of Hinduism.[191][192][193]

Hindu texts accept a polytheistic framework, but this is generally conceptualized as the divine essence or luminosity that gives vitality and animation to the inanimate natural substances.[194] There is a divine in everything, human beings, animals, trees and rivers. It is observable in offerings to rivers, trees, tools of one’s work, animals and birds, rising sun, friends and guests, teachers and parents.[194][195][196] It is the divine in these that makes each sacred and worthy of reverence. This seeing divinity in everything, state Buttimer and Wallin, makes the Vedic foundations of Hinduism quite distinct from Animism.[194] The animistic premise sees multiplicity, power differences and competition between man and man, man and animal, as well as man and nature. The Vedic view does not see this competition, rather sees a unifying divinity that connects everyone and everything.[194][197][198]

The Hindu scriptures refer to celestial entities called Devas (or devī in feminine form; devatā used synonymously for Deva in Hindi), which may be translated into English as gods or heavenly beings.[note 17] The devas are an integral part of Hindu culture and are depicted in art, architecture and through icons, and stories about them are related in the scriptures, particularly in Indian epic poetry and the Puranas. They are, however, often distinguished from Ishvara, a personal god, with many Hindus worshipping Ishvara in one of its particular manifestations as their iṣṭa devatā, or chosen ideal.[199][200] The choice is a matter of individual preference,[201] and of regional and family traditions.[201][note 18] The multitude of Devas are considered as manifestations of Brahman.[note 19]

The word avatar does not appear in the Vedic literature,[203] but appears in verb forms in post-Vedic literature, and as a noun particularly in the Puranic literature after the 6th century CE.[204] Theologically, the reincarnation idea is most often associated with the avatars of Hindu god Vishnu, though the idea has been applied to other deities.[205] Varying lists of avatars of Vishnu appear in Hindu scriptures, including the ten Dashavatara of the Garuda Purana and the twenty-two avatars in the Bhagavata Purana, though the latter adds that the incarnations of Vishnu are innumerable.[206] The avatars of Vishnu are important in Vaishnavism theology. In the goddess-based Shaktism tradition of Hinduism, avatars of the Devi are found and all goddesses are considered to be different aspects of the same metaphysical Brahman[207] and Shakti (energy).[208][209] While avatars of other deities such as Ganesha and Shiva are also mentioned in medieval Hindu texts, this is minor and occasional.[210]

Both theistic and atheistic ideas, for epistemological and metaphysical reasons, are profuse in different schools of Hinduism. The early Nyaya school of Hinduism, for example, was non-theist/atheist,[211] but later Nyaya school scholars argued that God exists and offered proofs using its theory of logic.[212][213] Other schools disagreed with Nyaya scholars. Samkhya,[214] Mimamsa[215] and Carvaka schools of Hinduism, were non-theist/atheist, arguing that “God was an unnecessary metaphysical assumption”.[216][web 4][217] Its Vaisheshika school started as another non-theistic tradition relying on naturalism and that all matter is eternal, but it later introduced the concept of a non-creator God.[218][219] The Yoga school of Hinduism accepted the concept of a “personal god” and left it to the Hindu to define his or her god.[220] Advaita Vedanta taught a monistic, abstract Self and Oneness in everything, with no room for gods or deity, a perspective that Mohanty calls, “spiritual, not religious”.[221] Bhakti sub-schools of Vedanta taught a creator God that is distinct from each human being.[190]

According to Graham Schweig, Hinduism has the strongest presence of the divine feminine in world religion from ancient times to the present.[222] The goddess is viewed as the heart of the most esoteric Saiva traditions.[223]

Authority

Authority and eternal truths play an important role in Hinduism.[224] Religious traditions and truths are believed to be contained in its sacred texts, which are accessed and taught by sages, gurus, saints or avatars.[224] But there is also a strong tradition of the questioning of authority, internal debate and challenging of religious texts in Hinduism. The Hindus believe that this deepens the understanding of the eternal truths and further develops the tradition. Authority “was mediated through […] an intellectual culture that tended to develop ideas collaboratively, and according to the shared logic of natural reason.”[224] Narratives in the Upanishads present characters questioning persons of authority.[224] The Kena Upanishad repeatedly asks kena, ‘by what’ power something is the case.[224] The Katha Upanishad and Bhagavad Gita present narratives where the student criticizes the teacher’s inferior answers.[224] In the Shiva Purana, Shiva questions Vishnu and Brahma.[224] Doubt plays a repeated role in the Mahabharata.[224] Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda presents criticism via the character of Radha.[224]

Main traditions

A Ganesha-centric Panchayatana (“five deities”, from the Smarta tradition): Ganesha (centre) with Shiva (top left), Parvati (top right), Vishnu (bottom left) and Surya (bottom right). All these deities also have separate sects dedicated to them.

Hinduism has no central doctrinal authority and many practising Hindus do not claim to belong to any particular denomination or tradition.[225] Four major denominations are, however, used in scholarly studies: Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism and Smartism.[226][227] These denominations differ primarily in the central deity worshipped, the traditions and the soteriological outlook.[228] The denominations of Hinduism, states Lipner, are unlike those found in major religions of the world, because Hindu denominations are fuzzy with individuals practicing more than one, and he suggests the term “Hindu polycentrism”.[229]

Vaishnavism is the devotional religious tradition that worships Vishnu[230] and his avatars, particularly Krishna and Rama.[231] The adherents of this sect are generally non-ascetic, monastic, oriented towards community events and devotionalism practices inspired by “intimate loving, joyous, playful” Krishna and other Vishnu avatars.[228] These practices sometimes include community dancing, singing of Kirtans and Bhajans, with sound and music believed by some to have meditative and spiritual powers.[232] Temple worship and festivals are typically elaborate in Vaishnavism.[233] The Bhagavad Gita and the Ramayana, along with Vishnu-oriented Puranas provide its theistic foundations.[234] Philosophically, their beliefs are rooted in the dualism sub-schools of Vedantic Hinduism.[235][236]

Shaivism is the tradition that focuses on Shiva. Shaivas are more attracted to ascetic individualism, and it has several sub-schools.[228] Their practices include Bhakti-style devotionalism, yet their beliefs lean towards nondual, monistic schools of Hinduism such as Advaita and Yoga.[226][232] Some Shaivas worship in temples, while others emphasize yoga, striving to be one with Shiva within.[237] Avatars are uncommon, and some Shaivas visualize god as half male, half female, as a fusion of the male and female principles (Ardhanarishvara). Shaivism is related to Shaktism, wherein Shakti is seen as spouse of Shiva.[226] Community celebrations include festivals, and participation, with Vaishnavas, in pilgrimages such as the Kumbh Mela.[238] Shaivism has been more commonly practiced in the Himalayan north from Kashmir to Nepal, and in south India.[239]

Shaktism focuses on goddess worship of Shakti or Devi as cosmic mother,[228] and it is particularly common in northeastern and eastern states of India such as Assam and Bengal. Devi is depicted as in gentler forms like Parvati, the consort of Shiva; or, as fierce warrior goddesses like Kali and Durga. Followers of Shaktism recognize Shakti as the power that underlies the male principle. Shaktism is also associated with Tantra practices.[240] Community celebrations include festivals, some of which include processions and idol immersion into sea or other water bodies.[241]

Smartism centers its worship simultaneously on all the major Hindu deities: Shiva, Vishnu, Shakti, Ganesha, Surya and Skanda.[242] The Smarta tradition developed during the (early) Classical Period of Hinduism around the beginning of the Common Era, when Hinduism emerged from the interaction between Brahmanism and local traditions.[243][244] The Smarta tradition is aligned with Advaita Vedanta, and regards Adi Shankara as its founder or reformer, who considered worship of God-with-attributes (Saguna Brahman) as a journey towards ultimately realizing God-without-attributes (nirguna Brahman, Atman, Self-knowledge).[245][246] The term Smartism is derived from Smriti texts of Hinduism, meaning those who remember the traditions in the texts.[226][247] This Hindu sect practices a philosophical Jnana yoga, scriptural studies, reflection, meditative path seeking an understanding of Self’s oneness with God.[226][248]

There are no census data available on demographic history or trends for the traditions within Hinduism.[249] Estimates vary on the relative number of adherents in the different traditions of Hinduism. According to a 2010 estimate by Johnson and Grim, the Vaishnavism tradition is the largest group with about 641 million or 67.6% of Hindus, followed by Shaivism with 252 million or 26.6%, Shaktism with 30 million or 3.2% and other traditions including Neo-Hinduism and Reform Hinduism with 25 million or 2.6%.[250] In contrast, according to Jones and Ryan, Shaivism is the largest tradition of Hinduism.[251]

Scriptures

The Rigveda is the first and most important Veda[252] and is one of the oldest religious texts. This Rigveda manuscript is in Devanagari.

The ancient scriptures of Hinduism are in Sanskrit. These texts are classified into two: Shruti and Smriti. Hindu scriptures were composed, memorized and transmitted verbally, across generations, for many centuries before they were written down.[253][254] Over many centuries, sages refined the teachings and expanded the Shruti and Smriti, as well as developed Shastras with epistemological and metaphysical theories of six classical schools of Hinduism.

Shruti (lit. that which is heard)[255] primarily refers to the Vedas, which form the earliest record of the Hindu scriptures, and are regarded as eternal truths revealed to the ancient sages (rishis).[256] There are four Vedas – Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda and Atharvaveda. Each Veda has been subclassified into four major text types – the Samhitas (mantras and benedictions), the Aranyakas (text on rituals, ceremonies, sacrifices and symbolic-sacrifices), the Brahmanas (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies and sacrifices), and the Upanishads (text discussing meditation, philosophy and spiritual knowledge).[257][258][259] The first two parts of the Vedas were subsequently called the Karmakāṇḍa (ritualistic portion), while the last two form the Jñānakāṇḍa (knowledge portion, discussing spiritual insight and philosophical teachings).[260][261][262][263]

The Upanishads are the foundation of Hindu philosophical thought, and have profoundly influenced diverse traditions.[264][265] Of the Shrutis (Vedic corpus), they alone are widely influential among Hindus, considered scriptures par excellence of Hinduism, and their central ideas have continued to influence its thoughts and traditions.[264][266] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan states that the Upanishads have played a dominating role ever since their appearance.[267] There are 108 Muktikā Upanishads in Hinduism, of which between 10 and 13 are variously counted by scholars as Principal Upanishads.[268][269]

The most notable of the Smritis (“remembered”) are the Hindu epics and the Puranas. The epics consist of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. The Bhagavad Gita is an integral part of the Mahabharata and one of the most popular sacred texts of Hinduism.[270] It is sometimes called Gitopanishad, then placed in the Shruti (“heard”) category, being Upanishadic in content.[271] The Puranas, which started to be composed from c. 300 CE onward,[272] contain extensive mythologies, and are central in the distribution of common themes of Hinduism through vivid narratives. The Yoga Sutras is a classical text for the Hindu Yoga tradition, which gained a renewed popularity in the 20th century.[273]

Since the 19th-century Indian modernists have re-asserted the ‘Aryan origins’ of Hinduism, “purifying” Hinduism from its Tantric elements[84] and elevating the Vedic elements. Hindu modernists like Vivekananda see the Vedas as the laws of the spiritual world, which would still exist even if they were not revealed to the sages.[274][275] In Tantric tradition, the Agamas refer to authoritative scriptures or the teachings of Shiva to Shakti,[276] while Nigamas refers to the Vedas and the teachings of Shakti to Shiva.[276] In Agamic schools of Hinduism, the Vedic literature and the Agamas are equally authoritative.[277][278]

Practices

Rituals

A wedding is the most extensive personal ritual an adult Hindu undertakes in his or her life. A typical Hindu wedding is solemnized before Vedic fire ritual (shown).[279]

Most Hindus observe religious rituals at home.[280] The rituals vary greatly among regions, villages, and individuals. They are not mandatory in Hinduism. The nature and place of rituals is an individual’s choice. Some devout Hindus perform daily rituals such as worshiping at dawn after bathing (usually at a family shrine, and typically includes lighting a lamp and offering foodstuffs before the images of deities), recitation from religious scripts, singing devotional hymns, yoga, meditation, chanting mantras and others.[281]

Vedic rituals of fire-oblation (yajna) and chanting of Vedic hymns are observed on special occasions, such as a Hindu wedding.[282] Other major life-stage events, such as rituals after death, include the yajña and chanting of Vedic mantras.[web 5]

Life-cycle rites of passage

Major life stage milestones are celebrated as sanskara (saṃskāra, rites of passage) in Hinduism.[283][284] The rites of passage are not mandatory, and vary in details by gender, community and regionally.[285] Gautama Dharmasutras composed in about the middle of 1st millennium BCE lists 48 sanskaras,[286] while Gryhasutra and other texts composed centuries later list between 12 and 16 sanskaras.[283][287] The list of sanskaras in Hinduism include both external rituals such as those marking a baby’s birth and a baby’s name giving ceremony, as well as inner rites of resolutions and ethics such as compassion towards all living beings and positive attitude.[286]

The major traditional rites of passage in Hinduism include[285] Garbhadhana (pregnancy), Pumsavana (rite before the fetus begins moving and kicking in womb), Simantonnayana (parting of pregnant woman’s hair, baby shower), Jatakarman (rite celebrating the new born baby), Namakarana (naming the child), Nishkramana (baby’s first outing from home into the world), Annaprashana (baby’s first feeding of solid food), Chudakarana (baby’s first haircut, tonsure), Karnavedha (ear piercing), Vidyarambha (baby’s start with knowledge), Upanayana (entry into a school rite),[288][289] Keshanta and Ritusuddhi (first shave for boys, menarche for girls), Samavartana (graduation ceremony), Vivaha (wedding), Vratas (fasting, spiritual studies) and Antyeshti (cremation for an adult, burial for a child).[290] In contemporary times, there is regional variation among Hindus as to which of these sanskaras are observed; in some cases, additional regional rites of passage such as Śrāddha (ritual of feeding people after cremation) are practiced.[285][web 6]

Bhakti (worship)

Bhakti refers to devotion, participation in and the love of a personal god or a representational god by a devotee.[291][292] Bhakti marga is considered in Hinduism as one of many possible paths of spirituality and alternative means to moksha.[293] The other paths, left to the choice of a Hindu, are Jnana marga (path of knowledge), Karma marga (path of works), Rāja marga (path of contemplation and meditation).[294][295]

Bhakti is practiced in a number of ways, ranging from reciting mantras, japas (incantations), to individual private prayers within one’s home shrine,[296] or in a temple or near a river bank, sometimes in the presence of an idol or image of a deity.[297][298] Hindu temples and domestic altars, states Lynn Foulston, are important elements of worship in contemporary theistic Hinduism.[299] While many visit a temple on a special occasion, most offer a brief prayer on an everyday basis at the domestic altar.[299] This bhakti is expressed in a domestic shrine which typically is a dedicated part of the home and includes the images of deities or the gurus the Hindu chooses.[299] Among Vaishnavism sub-traditions such as Swaminarayan, the home shrines can be elaborate with either a room dedicated to it or a dedicated part of the kitchen. The devotee uses this space for daily prayers or meditation, either before breakfast or after day’s work.[300][301]

Bhakti is sometimes private inside household shrines and sometimes practiced as a community. It may include Puja, Aarti,[302] musical Kirtan or singing Bhajan, where devotional verses and hymns are read or poems are sung by a group of devotees.[303][304] While the choice of the deity is at the discretion of the Hindu, the most observed traditions of Hindu devotionalism include Vaishnavism (Vishnu), Shaivism (Shiva) and Shaktism (Shakti).[305] A Hindu may worship multiple deities, all as henotheistic manifestations of the same ultimate reality, cosmic spirit and absolute spiritual concept called Brahman in Hinduism.[306][307][note 19]

Bhakti marga, states Pechelis, is more than ritual devotionalism, it includes practices and spiritual activities aimed at refining one’s state of mind, knowing god, participating in god, and internalizing god.[308][309] While Bhakti practices are popular and easily observable aspect of Hinduism, not all Hindus practice Bhakti, or believe in god-with-attributes (saguna Brahman).[310][311] Concurrent Hindu practices include a belief in god-without-attributes, and god within oneself.[312][313]

Festivals

The festival of lights, Diwali, is celebrated by Hindus all over the world.

Hindu festivals (Sanskrit: Utsava; literally: “to lift higher”) are ceremonies that weave individual and social life to dharma.[314][315] Hinduism has many festivals throughout the year, where the dates are set by the lunisolar Hindu calendar, many coinciding with either the full moon (Holi) or the new moon (Diwali), often with seasonal changes.[316] Some festivals are found only regionally and they celebrate local traditions, while a few such as Holi and Diwali are pan-Hindu.[316][317]

The festivals typically celebrate events from Hinduism, connoting spiritual themes and celebrating aspects of human relationships such as the Sister-Brother bond over the Raksha Bandhan (or Bhai Dooj) festival.[315][318] The same festival sometimes marks different stories depending on the Hindu denomination, and the celebrations incorporate regional themes, traditional agriculture, local arts, family get togethers, Puja rituals and feasts.[314][319]

Some major regional or pan-Hindu festivals include:

Pilgrimage

Many adherents undertake pilgrimages, which have historically been an important part of Hinduism and remain so today.[320] Pilgrimage sites are called Tirtha, Kshetra, Gopitha or Mahalaya.[321][322] The process or journey associated with Tirtha is called Tirtha-yatra.[323] According to the Hindu text Skanda Purana, Tirtha are of three kinds: Jangam Tirtha is to a place movable of a sadhu, a rishi, a guru; Sthawar Tirtha is to a place immovable, like Benaras, Haridwar, Mount Kailash, holy rivers; while Manas Tirtha is to a place of mind of truth, charity, patience, compassion, soft speech, soul.[324][325] Tīrtha-yatra is, states Knut A. Jacobsen, anything that has a salvific value to a Hindu, and includes pilgrimage sites such as mountains or forests or seashore or rivers or ponds, as well as virtues, actions, studies or state of mind.[326][327]

Pilgrimage sites of Hinduism are mentioned in the epic Mahabharata and the Puranas.[328][329] Most Puranas include large sections on Tirtha Mahatmya along with tourist guides,[330] which describe sacred sites and places to visit.[331][332][333] In these texts, Varanasi (Benares, Kashi), Rameshwaram, Kanchipuram, Dwarka, Puri, Haridwar, Sri Rangam, Vrindavan, Ayodhya, Tirupati, Mayapur, Nathdwara, twelve Jyotirlinga and Shakti Peetha have been mentioned as particularly holy sites, along with geographies where major rivers meet (sangam) or join the sea.[334][329] Kumbhamela is another major pilgrimage on the eve of the solar festival Makar Sankranti. This pilgrimage rotates at a gap of three years among four sites: Prayag Raj at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, Haridwar near source of the Ganges, Ujjain on the Shipra river and Nasik on the bank of the Godavari river.[335] This is one of world’s largest mass pilgrimage, with an estimated 40 to 100 million people attending the event.[335][336][337] At this event, they say a prayer to the sun and bathe in the river,[335] a tradition attributed to Adi Shankara.[338]

Some pilgrimages are part of a Vrata (vow), which a Hindu may make for a number of reasons.[339][340] It may mark a special occasion, such as the birth of a baby, or as part of a rite of passage such as a baby’s first haircut, or after healing from a sickness.[341][342] It may, states Eck, also be the result of prayers answered.[341] An alternative reason for Tirtha, for some Hindus, is to respect wishes or in memory of a beloved person after his or her death.[341] This may include dispersing their cremation ashes in a Tirtha region in a stream, river or sea to honor the wishes of the dead. The journey to a Tirtha, assert some Hindu texts, helps one overcome the sorrow of the loss.[341][note 20]

Other reasons for a Tirtha in Hinduism is to rejuvenate or gain spiritual merit by traveling to famed temples or bathe in rivers such as the Ganges.[345][346][347] Tirtha has been one of the recommended means of addressing remorse and to perform penance, for unintentional errors and intentional sins, in the Hindu tradition.[348][349] The proper procedure for a pilgrimage is widely discussed in Hindu texts.[350] The most accepted view is that the greatest austerity comes from traveling on foot, or part of the journey is on foot, and that the use of a conveyance is only acceptable if the pilgrimage is otherwise impossible.[351]

Person and society

Varnas

Brahmins at Bhadrachalam Temple, in Telangana

Hindu society has been categorised into four classes, called varnas. They are the Brahmins: Vedic teachers and priests; the Kshatriyas: warriors and kings; the Vaishyas: farmers and merchants; and the Shudras: servants and labourers.[352]

The Bhagavad Gītā links the varna to an individual’s duty (svadharma), inborn nature (svabhāva), and natural tendencies (guṇa).[353] The Manusmṛiti categorises the different castes.[web 7]

Some mobility and flexibility within the varnas challenge allegations of social discrimination in the caste system, as has been pointed out by several sociologists,[354][355] although some other scholars disagree.[356] Scholars debate whether the so-called caste system is part of Hinduism sanctioned by the scriptures or social custom.[357][web 8][note 21] And various contemporary scholars have argued that the caste system was constructed by the British colonial regime.[358]

A renunciant man of knowledge is usually called Varnatita or “beyond all varnas” in Vedantic works. The bhiksu is advised to not bother about the caste of the family from which he begs his food. Scholars like Adi Sankara affirm that not only is Brahman beyond all varnas, the man who is identified with Him also transcends the distinctions and limitations of caste.[359]

Yoga

A statue of Shiva in yogic meditation

In whatever way a Hindu defines the goal of life, there are several methods (yogas) that sages have taught for reaching that goal. Yoga is a Hindu discipline which trains the body, mind and consciousness for health, tranquility and spiritual insight. This is done through a system of postures and exercises to practise control of the body and mind.[360] Texts dedicated to Yoga include the Yoga Sutras, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Bhagavad Gita and, as their philosophical and historical basis, the Upanishads. Yoga is means, and the four major marga (paths) discussed in Hinduism are: Bhakti Yoga (the path of love and devotion), Karma Yoga (the path of right action), Rāja Yoga (the path of meditation), Jñāna Yoga (the path of wisdom)[361] An individual may prefer one or some yogas over others, according to his or her inclination and understanding. Practice of one yoga does not exclude others.

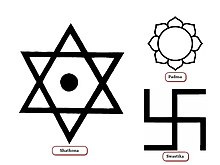

Symbolism

Hinduism has a developed system of symbolism and iconography to represent the sacred in art, architecture, literature and worship. These symbols gain their meaning from the scriptures or cultural traditions. The syllable Om (which represents the Brahman and Atman) has grown to represent Hinduism itself, while other markings such as the Swastika sign represent auspiciousness,[363] and Tilaka (literally, seed) on forehead – considered to be the location of spiritual third eye,[364] marks ceremonious welcome, blessing or one’s participation in a ritual or rite of passage.[365] Elaborate Tilaka with lines may also identify a devotee of a particular denomination. Flowers, birds, animals, instruments, symmetric mandala drawings, objects, idols are all part of symbolic iconography in Hinduism.[366][367]

Ahimsa, vegetarianism and other food customs

Hindus advocate the practice of ahiṃsā (nonviolence) and respect for all life because divinity is believed to permeate all beings, including plants and non-human animals.[368] The term ahiṃsā appears in the Upanishads,[369] the epic Mahabharata[370] and ahiṃsā is the first of the five Yamas (vows of self-restraint) in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.[371]

A goshala or cow shelter at Guntur

In accordance with ahiṃsā, many Hindus embrace vegetarianism to respect higher forms of life. Estimates of strict lacto vegetarians in India (includes adherents of all religions) who never eat any meat, fish or eggs vary between 20% and 42%, while others are either less strict vegetarians or non-vegetarians.[372] Those who eat meat seek Jhatka (quick death) method of meat production, and dislike Halal (slow bled death) method, believing that quick death method reduces suffering to the animal.[373][374] The food habits vary with region, with Bengali Hindus and Hindus living in Himalayan regions, or river delta regions, regularly eating meat and fish.[375] Some avoid meat on specific festivals or occasions.[376] Observant Hindus who do eat meat almost always abstain from beef. The cow in Hindu society is traditionally identified as a caretaker and a maternal figure,[377] and Hindu society honours the cow as a symbol of unselfish giving.[378]

There are many Hindu groups that have continued to abide by a strict vegetarian diet in modern times. Some adhere to a diet that is devoid of meat, eggs, and seafood.[379] Food affects body, mind and spirit in Hindu beliefs.[380][381] Hindu texts such as Śāṇḍilya Upanishad[382] and Svātmārāma[383][384] recommend Mitahara (eating in moderation) as one of the Yamas (virtuous self restraints). The Bhagavad Gita links body and mind to food one consumes in verses 17.8 through 17.10.[385]

Some Hindus such as those belonging to the Shaktism tradition,[386] and Hindus in regions such as Bali and Nepal[387][388] practise animal sacrifice.[387] The sacrificed animal is eaten as ritual food.[389] In contrast, the Vaishnava Hindus abhor and vigorously oppose animal sacrifice.[390][391] The principle of non-violence to animals has been so thoroughly adopted in Hinduism that animal sacrifice is uncommon[392] and historically reduced to a vestigial marginal practice.[393]

Institutions

Kauai Hindu monastery in Kauai Island in Hawaii is the only Hindu Monastery in the North American continent

Temple

A Hindu temple is a house of god(s).[394] It is a space and structure designed to bring human beings and gods together, infused with symbolism to express the ideas and beliefs of Hinduism.[395] A temple incorporates all elements of Hindu cosmology, the highest spire or dome representing Mount Meru – reminder of the abode of Brahma and the center of spiritual universe,[396] the carvings and iconography symbolically presenting dharma, kama, artha, moksha and karma.[397][398] The layout, the motifs, the plan and the building process recite ancient rituals, geometric symbolisms, and reflect beliefs and values innate within various schools of Hinduism.[395] Hindu temples are spiritual destinations for many Hindus (not all), as well as landmarks for arts, annual festivals, rite of passage rituals, and community celebrations.[399][400]

Hindu temples come in many styles, diverse locations, deploy different construction methods and are adapted to different deities and regional beliefs.[401] Two major styles of Hindu temples include the Gopuram style found in south India, and Nagara style found in north India.[402][403] Other styles include cave, forest and mountain temples.[404] Yet, despite their differences, almost all Hindu temples share certain common architectural principles, core ideas, symbolism and themes.[395]

Many temples feature one or more idols (murtis). The idol and Grabhgriya in the Brahma-pada (the center of the temple), under the main spire, serves as a focal point (darsana, a sight) in a Hindu temple.[405] In larger temples, the central space typically is surrounded by an ambulatory for the devotee to walk around and ritually circumambulate the Purusa (Brahman), the universal essence.[395]

Ashrama

Traditionally the life of a Hindu is divided into four Āśramas (phases or life stages; another meaning includes monastery).[406] The four ashramas are: Brahmacharya (student), Grihastha (householder), Vanaprastha (retired) and Sannyasa (renunciation).[407]

Brahmacharya represents the bachelor student stage of life. Grihastha refers to the individual’s married life, with the duties of maintaining a household, raising a family, educating one’s children, and leading a family-centred and a dharmic social life.[407] Grihastha stage starts with Hindu wedding, and has been considered as the most important of all stages in sociological context, as Hindus in this stage not only pursued a virtuous life, they produced food and wealth that sustained people in other stages of life, as well as the offsprings that continued mankind.[408] Vanaprastha is the retirement stage, where a person hands over household responsibilities to the next generation, took an advisory role, and gradually withdrew from the world.[409][410] The Sannyasa stage marks renunciation and a state of disinterest and detachment from material life, generally without any meaningful property or home (ascetic state), and focused on Moksha, peace and simple spiritual life.[411][412]

The Ashramas system has been one facet of the Dharma concept in Hinduism.[408] Combined with four proper goals of human life (Purusartha), the Ashramas system traditionally aimed at providing a Hindu with fulfilling life and spiritual liberation.[408] While these stages are typically sequential, any person can enter Sannyasa (ascetic) stage and become an Ascetic at any time after the Brahmacharya stage.[413] Sannyasa is not religiously mandatory in Hinduism, and elderly people are free to live with their families.[414]

Monasticism

A sadhu in Madurai, India

Some Hindus choose to live a monastic life (Sannyāsa) in pursuit of liberation (moksha) or another form of spiritual perfection.[20] Monastics commit themselves to a simple and celibate life, detached from material pursuits, of meditation and spiritual contemplation.[415] A Hindu monk is called a Sanyāsī, Sādhu, or Swāmi. A female renunciate is called a Sanyāsini. Renunciates receive high respect in Hindu society because of their simple ahimsa-driven lifestyle and dedication to spiritual liberation (moksha) – believed to be the ultimate goal of life in Hinduism.[412] Some monastics live in monasteries, while others wander from place to place, depending on donated food and charity for their needs.[416]

History

Periodisation

| Outline of South Asian history |

|---|

James Mill (1773–1836), in his The History of British India (1817),[417] distinguished three phases in the history of India, namely Hindu, Muslim and British civilisations.[417][418] This periodisation has been criticised for the misconceptions it has given rise to.[419] Another periodisation is the division into “ancient, classical, medieval and modern periods”.[420] An elaborate periodisation may be as follows:[13]

- Prevedic religions (pre-history and Indus Valley Civilisation; until c. 1500 BCE);

- Vedic period (c. 1500 – c. 500 BCE);

- “Second Urbanisation” (c. 500 – c. 200 BCE);

- Classical Hinduism (c. 200 BCE – c. 1100 CE);[note 22]

-

- Pre-classical Hinduism (c. 200 BCE – c. 300 CE);

- “Golden Age” (Gupta Empire) (c. 320 – c. 650 CE);

- Late-Classical Hinduism – Puranic Hinduism (c. 650 – c. 1100 CE);

- Islam and sects of Hinduism (c. 1200 – c. 1700 CE);

- Modern Hinduism (from c. 1800).

Origins

Hinduism is a fusion[426][note 3] or synthesis[10][note 4] of various Indian cultures and traditions.[10][note 5] Among the roots of Hinduism are the historical Vedic religion of Iron Age India,[427] itself already the product of “a composite of the Indo-Aryan and Harappan cultures and civilizations”,[428][note 23] but also the Sramana[429] or renouncer traditions[96] of northeast India,[429] and mesolithic[430] and neolithic[431] cultures of India, such as the religions of the Indus Valley Civilisation,[432] Dravidian traditions,[433] and the local traditions[96] and tribal religions.[434][note 24]

This “Hindu synthesis” emerged after the Vedic period, between 500[10]-200[11] BCE and c. 300 CE,[10] the beginning of the “Epic and Puranic” c.q. “Preclassical” period,[10][11] and incorporated śramaṇic[11][435] and Buddhist influences[11][436] and the emerging bhakti tradition into the Brahmanical fold via the Smriti literature.[437][11] From northern India this “Hindu synthesis”, and its societal divisions, spread to southern India and parts of Southeast Asia.[438]

Prevedic religions (until c. 1500 BCE)

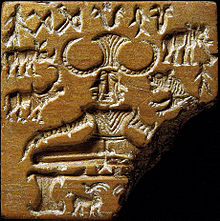

The Pashupati seal, Indus Valley civilization

The earliest prehistoric religion in India that may have left its traces in Hinduism comes from mesolithic as observed in the sites such as the rock paintings of Bhimbetka rock shelters dating to a period of 30,000 BCE or older,[note 25] as well as neolithic times.[note 26] Some of the religious practices can be considered to have originated in 4000 BCE. Several tribal religions still exist, though their practices may not resemble those of prehistoric religions.[web 10]

According to anthropologist Possehl, the Indus Valley Civilization “provides a logical, if somewhat arbitrary, starting point for some aspects of the later Hindu tradition”.[439] The religion of this period included worship of a Great male god, which is compared to a proto-Shiva, and probably a Mother Goddess, that may prefigure Shakti. However these links of deities and practices of the Indus religion to later-day Hinduism are subject to both political contention and scholarly dispute.[440]

Vedic period (c. 1500 – c. 500 BCE)

Origins and development

| showIndo-Aryan migration and Vedic period |

|---|

The Vedic period, named after the Vedic religion of the Indo-Aryans,[441][note 27] lasted from c. 1500 to 500 BCE.[443][note 28] The Indo-Aryans were semi-nomadic pastoralists[445] who migrated into north-western India after the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization.[442][446][447][note 29]

During the early Vedic period (c. 1500 – c. 1100 BCE[445]) Vedic tribes were pastoralists, wandering around in north-west India.[450] After 1100 BCE the Vedic tribes moved into the western Ganges Plain, adapting an agrarian lifestyle.[445][451][452] Rudimentary state-forms appeared, of which the Kuru-Pañcāla union was the most influential.[453][454] It was a tribal union, which developed into the first recorded state-level society in South Asia around 1000 BCE.[445] This, according to Witzel, decisively changed the Vedic heritage of the early Vedic period, collecting the Vedic hymns into collections, and shifting ritual exchange within a tribe to social exchange within the larger Kuru realm through complicated Srauta rituals.[455] In this period, states Samuel, emerged the Brahmana and Aranyaka layers of Vedic texts, which merged into the earliest Upanishads.[456] These texts began to ask the meaning of a ritual, adding increasing levels of philosophical and metaphysical speculation,[456] or “Hindu synthesis”.[10]

Vedic religion

The Indo-Aryans brought with them their language[457] and religion.[458][459] The Vedic beliefs and practices of the pre-classical era were closely related to the hypothesised Proto-Indo-European religion,[460] and the Indo-Iranian religion.[461][note 30]

The Vedic religion history is unclear and “heavily contested”, states Samuel.[468] In the later Vedic period, it co-existed with local religions, such as the mother goddess worshipping Yaksha cults.[469][web 11] The Vedic was itself likely the product of “a composite of the indo-Aryan and Harappan cultures and civilizations”.[428] David Gordon White cites three other mainstream scholars who “have emphatically demonstrated” that Vedic religion is partially derived from the Indus Valley Civilizations.[470][note 23] Their religion was further developed when they migrated into the Ganges Plain after c. 1100 BCE and became settled farmers,[445][472][473] further syncretising with the native cultures of northern India.[474]

The composition of the Vedic literature began in the 2nd millennium BCE.[475][476] The oldest of these Vedic texts is the Rigveda, composed between c. 1500 – 1200 BCE,[477][478][479] though a wider approximation of c. 1700 – 1100 BCE has also been given.[480][481]

The first half of the 1st millennium BCE was a period of great intellectual and social-cultural ferment in ancient India.[482][483][note 31] New ideas developed both in the Vedic tradition in the form of the Upanishads, and outside of the Vedic tradition through the Śramaṇa movements.[485][486][487] For example, prior to the birth of the Buddha and the Mahavira, and related Sramana movements, the Brahmanical tradition had questioned the meaning and efficacy of Vedic rituals,[488] then internalized and variously reinterpreted the Vedic fire rituals as ethical concepts such as Truth, Rite, Tranquility or Restraint.[489] The 9th and 8th centuries BCE witnessed the composition of the earliest Upanishads with such ideas.[489][490]:183 Other ancient Principal Upanishads were composed in the centuries that followed, forming the foundation of classical Hinduism and the Vedanta (conclusion of the Veda) literature.[491]

“Second Urbanisation” (c. 500 – c. 200 BCE)

Increasing urbanisation of India between 800 and 400 BCE, and possibly the spread of urban diseases, contributed to the rise of ascetic movements and of new ideas which challenged the orthodox Brahmanism.[492] These ideas led to Sramana movements, of which Mahavira (c. 549 – 477 BCE), proponent of Jainism, and Buddha (c. 563 – 483), founder of Buddhism, were the most prominent icons.[490]:184 According to Bronkhorst, the sramana culture arose in “greater Magadha,” which was Indo-European, but not Vedic. In this culture, kashtriyas were placed higher than Brahmins, and it rejected Vedic authority and rituals.[493][494] Geoffrey Samuel, following Tom Hopkins, also argues that the Gangetic plain, which gave rise to Jainism and Buddhism, incorporated a culture which was different form the Brahmanical orthodoxy practiced in the Kuru-Pancala region.[495]

The ascetic tradition of Vedic period in part created the foundational theories of samsara and of moksha (liberation from samsara), which became characteristic for Hinduism, along with Buddhism and Jainism.[note 32][496]

These ascetic concepts were adopted by schools of Hinduism as well as other major Indian religions, but key differences between their premises defined their further development. Hinduism, for example, developed its ideas with the premise that every human being has a soul (atman, self), while Buddhism developed with the premise that there is no soul or self.[497][498][499]

The chronology of these religious concepts is unclear, and scholars contest which religion affected the other as well as the chronological sequence of the ancient texts.[500][501] Pratt notes that Oldenberg (1854–1920), Neumann (1865–1915) and Radhakrishnan (1888–1975) believed that the Buddhist canon had been influenced by Upanishads, while la Vallee Poussin thinks the influence was nihil, and “Eliot and several others insist that on some points such as the existence of soul or self the Buddha was directly antithetical to the Upanishads”.[502][note 33]

Classical Hinduism (c. 200 BCE – c. 1100 CE)

From about 500 BCE through about 300 CE, the Vedic-Brahmanic synthesis or “Hindu synthesis” continued.[10] Classical Hindu and Sramanic (particularly Buddhist) ideas spread within Indian subcontinent, as well outside India such as in Central Asia,[504] and the parts of Southeast Asia (coasts of Indonesia and peninsular Thailand).[note 34][505]

- Pre-classical Hinduism (c. 200 BCE – c. 300 CE)