Animism

Animism (from Latin anima, “breath, spirit, life“)[1][2] is the religious belief that objects, places and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence.[3][4][5][6] Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork and perhaps even words—as animated and alive. Animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many indigenous peoples,[7] especially in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organised religions.[8]

Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, “animism” is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples’ “spiritual” or “supernatural” perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to “animism” (or even “religion”);[9] the term is an anthropological construct.

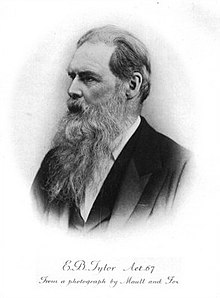

Largely due to such ethnolinguistic and cultural discrepancies, opinion has differed on whether animism refers to an ancestral mode of experience common to indigenous peoples around the world, or to a full-fledged religion in its own right. The currently accepted definition of animism was only developed in the late 19th century (1871) by Sir Edward Tylor, who created it as “one of anthropology‘s earliest concepts, if not the first”.[10][11]

Animism encompasses the beliefs that all material phenomena have agency, that there exists no hard and fast distinction between the spiritual and physical (or material) world and that soul or spirit or sentience exists not only in humans, but also in other animals, plants, rocks, geographic features such as mountains or rivers or other entities of the natural environment: water sprites, vegetation deities, tree sprites, … . Animism may further attribute a life force to abstract concepts such as words, true names or metaphors in mythology. Some members of the non-tribal world also consider themselves animists (such as author Daniel Quinn, sculptor Lawson Oyekan and many contemporary Pagans).[12]

Contents

Theories[edit]

Old animism[edit]

Earlier anthropological perspectives, which have since been termed the “old animism”, were concerned with knowledge on what is alive and what factors make something alive.[13] The “old animism” assumed that animists were individuals who were unable to understand the difference between persons and things.[14] Critics of the “old animism” have accused it of preserving “colonialist and dualist worldviews and rhetoric”.[15]

Edward Tylor’s definition[edit]

Edward Tylor developed animism as an anthropological theory.

The idea of animism was developed by the anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor in his 1871 book Primitive Culture,[1] in which he defined it as “the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general”. According to Tylor, animism often includes “an idea of pervading life and will in nature”;[16] a belief that natural objects other than humans have souls. That formulation was little different from that proposed by Auguste Comte as “fetishism“,[17] but the terms now have distinct meanings.

For Tylor, animism represented the earliest form of religion, being situated within an evolutionary framework of religion which has developed in stages and which will ultimately lead to humanity rejecting religion altogether in favor of scientific rationality.[18] Thus, for Tylor, animism was fundamentally seen as a mistake, a basic error from which all religion grew.[18] He did not believe that animism was inherently illogical, but he suggested that it arose from early humans’ dreams and visions and thus was a rational system. However, it was based on erroneous, unscientific observations about the nature of reality.[19] Stringer notes that his reading of Primitive Culture led him to believe that Tylor was far more sympathetic in regard to “primitive” populations than many of his contemporaries and that Tylor expressed no belief that there was any difference between the intellectual capabilities of “savage” people and Westerners.[4]

Tylor had initially wanted to describe the phenomenon as “spiritualism” but realised that would cause confusion with the modern religion of Spiritualism, that was then prevalent across Western nations.[20] He adopted the term “animism” from the writings of the German scientist Georg Ernst Stahl,[21] who, in 1708, had developed the term animismus as a biological theory that souls formed the vital principle and that the normal phenomena of life and the abnormal phenomena of disease could be traced to spiritual causes.[22] The first known usage in English appeared in 1819.[23]

The idea that there had once been “one universal form of primitive religion” (whether labelled “animism”, “totemism”, or “shamanism”) has been dismissed as “unsophisticated” and “erroneous” by the archaeologist Timothy Insoll, who stated that “it removes complexity, a precondition of religion now, in all its variants”.[24]

Social evolutionist conceptions[edit]

Tylor’s definition of animism was a part of a growing international debate on the nature of “primitive society” by lawyers, theologians and philologists. The debate defined the field of research of a new science: anthropology. By the end of the 19th century, an orthodoxy on “primitive society” had emerged, but few anthropologists still would accept that definition. The “19th-century armchair anthropologists” argued “primitive society” (an evolutionary category) was ordered by kinship and was divided into exogamous descent groups related by a series of marriage exchanges. Their religion was animism, the belief that natural species and objects had souls. With the development of private property, the descent groups were displaced by the emergence of the territorial state. These rituals and beliefs eventually evolved over time into the vast array of “developed” religions. According to Tylor, the more scientifically advanced a society became, the fewer members of that society believed in animism. However, any remnant ideologies of souls or spirits, to Tylor, represented “survivals” of the original animism of early humanity.[25]

—Graham Harvey, 2005.[26]

In 1869 (three years after Tylor proposed his definition of animism), the Edinburgh lawyer, John Ferguson McLennan, argued that the animistic thinking evident in fetishism gave rise to a religion he named Totemism. Primitive people believed, he argued, that they were descended of the same species as their totemic animal.[17] Subsequent debate by the ‘armchair anthropologists’ (including J. J. Bachofen, Émile Durkheim and Sigmund Freud) remained focused on totemism rather than animism, with few directly challenging Tylor’s definition. Indeed, anthropologists “have commonly avoided the issue of Animism and even the term itself rather than revisit this prevalent notion in light of their new and rich ethnographies.”[27]

According to the anthropologist Tim Ingold, animism shares similarities to totemism but differs in its focus on individual spirit beings which help to perpetuate life, whereas totemism more typically holds that there is a primary source, such as the land itself or the ancestors, who provide the basis to life. Certain indigenous religious groups such as the Australian Aboriginals are more typically totemic, whereas others like the Inuit are more typically animistic in their worldview.[28]

From his studies into child development, Jean Piaget suggested that children were born with an innate animist worldview in which they anthropomorphized inanimate objects, and that it was only later that they grew out of this belief.[29] Conversely, from her ethnographic research, Margaret Mead argued the opposite, believing that children were not born with an animist worldview but that they became acculturated to such beliefs as they were educated by their society.[29] Stewart Guthrie saw animism – or “attribution” as he preferred it – as an evolutionary strategy to aid survival. He argued that both humans and other animal species view inanimate objects as potentially alive as a means of being constantly on guard against potential threats.[30] His suggested explanation, however, did not deal with the question of why such a belief became central to religion.[31]

In 2000, Guthrie suggested that the “most widespread” concept of animism was that it was the “attribution of spirits to natural phenomena such as stones and trees”.[32]

The new animism[edit]

Many anthropologists ceased using the term “animism”, deeming it to be too close to early anthropological theory and religious polemic.[15] However, the term had also been claimed by religious groups – namely indigenous communities and nature worshipers – who felt that it aptly described their own beliefs, and who in some cases actively identified as “animists”.[33] It was thus readopted by various scholars, however they began using the term in a different way,[15] placing the focus on knowing how to behave toward other persons, some of whom aren’t human.[13] As the religious studies scholar Graham Harvey stated, while the “old animist” definition had been problematic, the term “animism” was nevertheless “of considerable value as a critical, academic term for a style of religious and cultural relating to the world.”[34]

Five Ojibwe chiefs in the 19th century; it was anthropological studies of Ojibwe religion that resulted in the development of the “new animism”.

The “new animism” emerged largely from the publications of the anthropologist Irving Hallowell which were produced on the basis of his ethnographic research among the Ojibwe communities of Canada in the mid-20th century.[35] For the Ojibwe encountered by Hallowell, personhood did not require human-likeness, but rather humans were perceived as being like other persons, who for instance included rock persons and bear persons.[36] For the Ojibwe, these persons were each wilful beings who gained meaning and power through their interactions with others; through respectfully interacting with other persons, they themselves learned to “act as a person”.[36] Hallowell’s approach to the understanding of Ojibwe personhood differed strongly from prior anthropological concepts of animism.[37] He emphasized the need to challenge the modernist, Western perspectives of what a person is by entering into a dialogue with different worldwide-views.[36]

Hallowell’s approach influenced the work of anthropologist Nurit Bird-David, who produced a scholarly article reassessing the idea of animism in 1999.[38] Seven comments from other academics were provided in the journal, debating Bird-David’s ideas.[39]

More recently post-modern anthropologists are increasingly engaging with the concept of animism. Modernism is characterized by a Cartesian subject-object dualism that divides the subjective from the objective, and culture from nature; in this view, Animism is the inverse of scientism, and hence inherently invalid. Drawing on the work of Bruno Latour, these anthropologists question these modernist assumptions, and theorize that all societies continue to “animate” the world around them, and not just as a Tylorian survival of primitive thought. Rather, the instrumental reason characteristic of modernity is limited to our “professional subcultures,” which allows us to treat the world as a detached mechanical object in a delimited sphere of activity. We, like animists, also continue to create personal relationships with elements of the so-called objective world, whether pets, cars or teddy-bears, who we recognize as subjects. As such, these entities are “approached as communicative subjects rather than the inert objects perceived by modernists.”[40] These approaches are careful to avoid the modernist assumptions that the environment consists dichotomously of a physical world distinct from humans, and from modernist conceptions of the person as composed dualistically as body and soul.[27]

Nurit Bird-David argues that “Positivistic ideas about the meaning of ‘nature’, ‘life’ and ‘personhood’ misdirected these previous attempts to understand the local concepts. Classical theoreticians (it is argued) attributed their own modernist ideas of self to ‘primitive peoples’ while asserting that the ‘primitive peoples’ read their idea of self into others!”[27] She argues that animism is a “relational epistemology”, and not a Tylorian failure of primitive reasoning. That is, self-identity among animists is based on their relationships with others, rather than some distinctive feature of the self. Instead of focusing on the essentialized, modernist self (the “individual”), persons are viewed as bundles of social relationships (“dividuals”), some of which are with “superpersons” (i.e. non-humans).

Guthrie expressed criticism of Bird-David’s attitude toward animism, believing that it promulgated the view that “the world is in large measure whatever our local imagination makes it”. This, he felt, would result in anthropology abandoning “the scientific project”.[41]

Tim Ingold, like Bird-David, argues that animists do not see themselves as separate from their environment: “Hunter-gatherers do not, as a rule, approach their environment as an external world of nature that has to be ‘grasped’ intellectually … indeed the separation of mind and nature has no place in their thought and practice.”[42] Willerslev extends the argument by noting that animists reject this Cartesian dualism, and that the animist self identifies with the world, “feeling at once within and apart from it so that the two glide ceaselessly in and out of each other in a sealed circuit.”[43] The animist hunter is thus aware of himself as a human hunter, but, through mimicry is able to assume the viewpoint, senses, and sensibilities of his prey, to be one with it.[44] Shamanism, in this view, is an everyday attempt to influence spirits of ancestors and animals by mirroring their behaviours as the hunter does his prey.

Cultural ecologist and philosopher David Abram articulates and elaborates an intensely ethical and ecological form of animism grounded in the phenomenology of sensory experience. In his books Becoming Animal and The Spell of the Sensuous, Abram suggests that material things are never entirely passive in our direct experience, holding rather that perceived things actively “solicit our attention” or “call our focus,” coaxing the perceiving body into an ongoing participation with those things. In the absence of intervening technologies, sensory experience is inherently animistic, disclosing a material field that is animate and self-organizing from the get-go. Drawing upon contemporary cognitive and natural science, as well as upon the perspectival worldviews of diverse indigenous, oral cultures, Abram proposes a richly pluralist and story-based cosmology, in which matter is alive through and through. Such an ontology is in close accord, he suggests, with our spontaneous perceptual experience; it would draw us back to our senses and to the primacy of the sensuous terrain, enjoining a more respectful and ethical relation to the more-than-human community of animals, plants, soils, mountains, waters and weather-patterns that materially sustains us.[45] In contrast to a long-standing tendency in the Western social sciences, which commonly provide rational explanations of animistic experience, Abram develops an animistic account of reason itself. He holds that civilized reason is sustained only by an intensely animistic participation between human beings and their own written signs. Indeed, as soon as we turn our gaze toward the alphabetic letters written on a page or a screen, these letters speak to us—we ‘see what they say’—much as ancient trees and gushing streams and lichen-encrusted boulders once spoke to our oral ancestors. Hence reading is an intensely concentrated form of animism, one that effectively eclipses all of the other, older, more spontaneous forms of participation in which we once engaged. “To tell the story in this manner—to provide an animistic account of reason, rather than the other way around—is to imply that animism is the wider and more inclusive term, and that oral, mimetic modes of experience still underlie, and support, all our literate and technological modes of reflection. When reflection’s rootedness in such bodily, participatory modes of experience is entirely unacknowledged or unconscious, reflective reason becomes dysfunctional, unintentionally destroying the corporeal, sensuous world that sustains it.”[46]

The religious studies scholar Graham Harvey defined animism as the belief “that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship with others”.[13] He added that it is therefore “concerned with learning how to be a good person in respectful relationships with other persons”.[13] Graham Harvey, in his 2013 Handbook of Contemporary Animism, identifies the animist perspective in line with Martin Buber’s “I-thou” as opposed to “I-it”. In such, Harvey says, the Animist takes an I-thou approach to relating to his world, where objects and animals are treated as a “thou” rather than as an “it”.[47]

Religion[edit]

A tableau presenting figures of various cultures filling in mediator-like roles, often being termed as “shaman” in the literature

Animist altar, Bozo village, Mopti, Bandiagara, Mali in 1972

There is ongoing disagreement (and no general consensus) as to whether animism is merely a singular, broadly encompassing religious belief[48] or a worldview in and of itself, comprising many diverse mythologies found worldwide in many diverse cultures.[49][50] This also raises a controversy regarding the ethical claims animism may or may not make: whether animism ignores questions of ethics altogether[51] or, by endowing various non-human elements of nature with spirituality or personhood,[52] in fact promotes a complex ecological ethics.[53]

Fetishism/totemism[edit]

In many animistic world views, the human being is often regarded as on a roughly equal footing with other animals, plants, and natural forces.[54]

Shamanism[edit]

A shaman is a person regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.[55] According to Mircea Eliade, shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments/illness by mending the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul/spirit restores the physical body of the individual to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community. Shamans may visit other worlds/dimensions to bring guidance to misguided souls and to ameliorate illnesses of the human soul caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the ailment.[56]

Abram, however, articulates a less supernatural and much more ecological understanding of the shaman’s role than that propounded by Eliade. Drawing upon his own field research in Indonesia, Nepal, and the Americas, Abram suggests that in animistic cultures, the shaman functions primarily as an intermediary between the human community and the more-than-human community of active agencies — the local animals, plants, and landforms (mountains, rivers, forests, winds and weather patterns, all of whom are felt to have their own specific sentience). Hence, the shaman’s ability to heal individual instances of dis-ease (or imbalance) within the human community is a by-product of her/his more continual practice of balancing the reciprocity between the human community and the wider collective of animate beings in which that community is embedded.[57]

Distinction from pantheism[edit]

Animism is not the same as pantheism, although the two are sometimes confused. Some religions are both pantheistic and animistic. One of the main differences is that while animists believe everything to be spiritual in nature, they do not necessarily see the spiritual nature of everything in existence as being united (monism), the way pantheists do. As a result, animism puts more emphasis on the uniqueness of each individual soul. In pantheism, everything shares the same spiritual essence, rather than having distinct spirits and/or souls.[58][59]

Examples[edit]

- Mun (also called Munism or Bongthingism) is the traditional polytheistic, animist, shamanistic, and syncretic religion of the Lepcha people.[60][61][62]

- Shinto (including the Ryukyuan religion) is the traditional Japanese folk religion and has many animist aspects.

- Korean shamanism, similar to Shinto, has many animist aspects.

- The traditional African religions are the religious traditions of Sub-Saharan Africa, which are basically a complex form of animism with polytheistic and shamanistic elements and ancestor worship.[63]

- The traditional Berber religion and the pre-Islamic Arab religion are the traditional polytheistic, animist, and in some rare cases, shamanistic, religions of the Berber and Arabic people.

- Dravidian folk religion, the traditional animist, polytheistic and partially shamanistic folk religion of the Dravidian people before the introduction of Hinduism or Buddhism.

- The New Age movement commonly demonstrates animistic traits in asserting the existence of nature spirits.[64]

- Some Neopagan groups, including Eco-pagans, describe themselves as animists, meaning that they respect the diverse community of living beings and spirits with whom humans share the world/cosmos.[65]

- The Kalash people of Northern Pakistan follow an ancient animistic religion.[66]

Animist life[edit]

Animals, plants, and the elements[edit]

Animism entails the belief that “all living things have a soul”, and thus a central concern of animist thought surrounds how animals can be eaten or otherwise used for humans’ subsistence needs.[67] The actions of non-human animals are viewed as “intentional, planned and purposive”,[68] and they are understood to be persons because they are both alive and communicate with others.[69] In animist world-views, non-human animals are understood to participate in kinship systems and ceremonies with humans, as well as having their own kinship systems and ceremonies.[70] Harvey cited an example of an animist understanding of animal behaviour that occurred at a powwow held by the Conne River Mi’kmaq in 1996; an eagle flew over the proceedings, circling over the central drum group. The assembled participants called out kitpu (“eagle”), conveying welcome to the bird and expressing pleasure at its beauty, and they later articulated the view that the eagle’s actions reflected its approval of the event and the Mi’kmaq’s return to traditional spiritual practices.[71]

Some animists also view plant and fungi life as persons and interact with them accordingly.[72] The most common encounter between humans and these plant and fungi persons is with the former’s collection of the latter for food, and for animists this interaction typically has to be carried out respectfully.[73] Harvey cited the example of Maori communities in New Zealand, who often offer karakia invocations to sweet potatoes as they dig the latter up; while doing so there is an awareness of a kinship relationship between the Maori and the sweet potatoes, with both understood as having arrived in Aotearoa together in the same canoes.[73] In other instances, animists believe that interaction with plant and fungi persons can result in the communication of things unknown or even otherwise unknowable.[72] Among some modern Pagans, for instance, relationships are cultivated with specific trees, who are understood to bestow knowledge or physical gifts, such as flowers, sap, or wood that can be used as firewood or to fashion into a wand; in return, these Pagans give offerings to the tree itself, which can come in the form of libations of mead or ale, a drop of blood from a finger, or a strand of wool.[74]

Various animistic cultures also comprehend stones as persons.[75] Discussing ethnographic work conducted among the Ojibwe, Harvey noted that their society generally conceived of stones as being inanimate, but with two notable exceptions: the stones of the Bell Rocks and those stones which are situated beneath trees struck by lightning, which were understood to have become Thunderers themselves.[76] The Ojibwe conceived of weather as being capable of having personhood, with storms being conceived of as persons known as ‘Thunderers’ whose sounds conveyed communications and who engaged in seasonal conflict over the lakes and forests, throwing lightning at lake monsters.[76] Wind, similarly, can be conceived as a person in animistic thought.[77]

The importance of place is also a recurring element of animism, with some places being understood to be persons in their own right.[78]

Spirits[edit]

Animism can also entail relationships being established with non-corporeal spirit entities.[79]

Other usages[edit]

Science and animism[edit]

In the early 20th century, William McDougall defended a form of Animism in his book Body and Mind: A History and Defence of Animism (1911).

The physicist Nick Herbert has argued for “quantum animism” in which mind permeates the world at every level.

The quantum consciousness assumption, which amounts to a kind of “quantum animism” likewise asserts that consciousness is an integral part of the physical world, not an emergent property of special biological or computational systems. Since everything in the world is on some level a quantum system, this assumption requires that everything be conscious on that level. If the world is truly quantum animated, then there is an immense amount of invisible inner experience going on all around us that is presently inaccessible to humans, because our own inner lives are imprisoned inside a small quantum system, isolated deep in the meat of an animal brain.[80]

Werner Krieglstein wrote regarding his quantum Animism:

Herbert’s quantum Animism differs from traditional Animism in that it avoids assuming a dualistic model of mind and matter. Traditional dualism assumes that some kind of spirit inhabits a body and makes it move, a ghost in the machine. Herbert’s quantum Animism presents the idea that every natural system has an inner life, a conscious center, from which it directs and observes its action.[81]

Ashley Curtis has argued in Error and Loss: A Licence to Enchantment[82] that the Cartesian idea of an experiencing subject facing off with an inert physical world is incoherent at its very foundation, and that this incoherence is predicted rather than belied by Darwinism. Human reason (and its rigorous extension in the natural sciences) fits an evolutionary niche just as echolocation does for bats and infrared vision does for pit vipers, and is—according to western science’s own dictates—epistemologically on a par with rather than superior to such capabilities. The meaning or aliveness of the “objects” we encounter—rocks, trees, rivers, other animals—thus depends for its validity not on a detached cognitive judgment but purely on the quality of our experience. The animist experience, and, indeed, the wolf’s or raven’s experience, thus become licensed as equally valid world-views to the modern western scientific one—indeed, they are more valid, since they are not plagued with the incoherence that inevitably crops up when “objective existence” is separated from “subjective experience.”

Socio-political impact[edit]

Harvey opined that animism’s views on personhood represented a radical challenge to the dominant perspectives of modernity, because it accords “intelligence, rationality, consciousness, volition, agency, intentionality, language and desire” to non-humans.[83] Similarly, it challenges the view of human uniqueness that is prevalent in both Abrahamic religions and Western rationalism.[84]

In art and literature[edit]

Animist beliefs can also be expressed through artwork.[85] For instance, among the Maori communities of New Zealand, there is an acknowledgment that creating art through carving wood or stone entails violence against the wood or stone person, and that the persons who are damaged therefore have to be placated and respected during the process; any excess or waste from the creation of the artwork is returned to the land, while the artwork itself is treated with particular respect.[86] Harvey therefore argued that the creation of art among the Maori was not about creating an inanimate object for display, but rather a transformation of different persons within a relationship.[87]

Harvey expressed the view that animist worldviews were present in various works of literature, citing such examples as the writings of Alan Garner, Leslie Silko, Barbara Kingsolver, Alice Walker, Daniel Quinn, Linda Hogan, David Abram, Patricia Grace, Chinua Achebe, Ursula Le Guin, Louise Erdrich, and Marge Piercy.[88] Animist worldviews have also been identified in the animated films of Hayao Miyazaki.[89][90][91][92]