Turkish language

Jump to navigationJump to search

| Turkish | |

|---|---|

| Türkçe (noun, adverb) Türk dili (noun) |

|

| Pronunciation | Türkçe: [ˈtyɾctʃe] ( Türk dili: Turkish pronunciation: [ˈtyɾc ‘dili] |

| Native to | Turkey (official), Northern Cyprus (official), Cyprus (official), Azerbaijan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Region | Anatolia, Balkans, Cyprus, Mesopotamia, Levant, Transcaucasia |

| Ethnicity | Turkish people |

|

Native speakers

|

75.7 million[1] (2002–2018) 88 million (L1 + L2)[2] |

|

Turkic

|

|

|

Early forms

|

|

|

Standard forms

|

Istanbul Turkish

|

| Dialects | |

| Latin (Turkish alphabet) Turkish Braille |

|

| Official status | |

|

Official language in

|

|

|

Recognised minority

language in |

|

| Regulated by | Turkish Language Association |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | tr |

| ISO 639-2 | tur |

| ISO 639-3 | tur |

| Glottolog | nucl1301[8] |

| Linguasphere | part of 44-AAB-a |

Countries where Turkish is an official language

Countries where it is recognized as a minority language

Countries where it is recognized as a minority language and co-official in at least one municipality

|

|

Turkish (Türkçe (![]() listen), Türk dili), also referred to as Istanbul Turkish[9][10][11] (İstanbul Türkçesi) or Turkey Turkish (Türkiye Türkçesi), is the most widely spoken of the Turkic languages, with around 70 to 80 million speakers, mostly in Turkey. Outside its native country, significant smaller groups of speakers exist in Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, North Macedonia,[12] Northern Cyprus,[13] Greece,[14] the Caucasus, and other parts of Europe and Central Asia. Cyprus has requested that the European Union add Turkish as an official language, even though Turkey is not a member state.[15]

listen), Türk dili), also referred to as Istanbul Turkish[9][10][11] (İstanbul Türkçesi) or Turkey Turkish (Türkiye Türkçesi), is the most widely spoken of the Turkic languages, with around 70 to 80 million speakers, mostly in Turkey. Outside its native country, significant smaller groups of speakers exist in Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, North Macedonia,[12] Northern Cyprus,[13] Greece,[14] the Caucasus, and other parts of Europe and Central Asia. Cyprus has requested that the European Union add Turkish as an official language, even though Turkey is not a member state.[15]

To the west, the influence of Ottoman Turkish—the variety of the Turkish language that was used as the administrative and literary language of the Ottoman Empire—spread as the Ottoman Empire expanded. In 1928, as one of Atatürk’s Reforms in the early years of the Republic of Turkey, the Ottoman Turkish alphabet was replaced with a Latin alphabet.

The distinctive characteristics of the Turkish language are vowel harmony and extensive agglutination. The basic word order of Turkish is subject–object–verb. Turkish has no noun classes or grammatical gender. The language makes usage of honorifics and has a strong T–V distinction which distinguishes varying levels of politeness, social distance, age, courtesy or familiarity toward the addressee. The plural second-person pronoun and verb forms are used referring to a single person out of respect.

Classification

Old Turkic Kul-chur inscription with the Old Turkic alphabet (c. 8th century). Töv Province, Mongolia

About 40% of all speakers of Turkic languages are native Turkish speakers.[16] The characteristic features of Turkish, such as vowel harmony, agglutination, and lack of grammatical gender, are universal within the Turkic family. The Turkic family comprises some 30 living languages spoken across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Siberia.

Turkish is a member of the Oghuz group of languages, a subgroup of the Turkic language family. There is a high degree of mutual intelligibility between Turkish and the other Oghuz Turkic languages, including Azerbaijani, Turkmen, Qashqai, Gagauz, and Balkan Gagauz Turkish.[17]

The Turkic languages were grouped into the controversial Altaic language group.

History

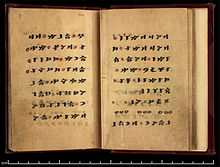

The 10th-century Irk Bitig or “Book of Divination”

The earliest known Old Turkic inscriptions are the three monumental Orkhon inscriptions found in modern Mongolia. Erected in honour of the prince Kul Tigin and his brother Emperor Bilge Khagan, these date back to the Second Turkic Khaganate.[18] After the discovery and excavation of these monuments and associated stone slabs by Russian archaeologists in the wider area surrounding the Orkhon Valley between 1889 and 1893, it became established that the language on the inscriptions was the Old Turkic language written using the Old Turkic alphabet, which has also been referred to as “Turkic runes” or “runiform” due to a superficial similarity to the Germanic runic alphabets.[19]

With the Turkic expansion during Early Middle Ages (c. 6th–11th centuries), peoples speaking Turkic languages spread across Central Asia, covering a vast geographical region stretching from Siberia all the way to Europe and the Mediterranean. The Seljuqs of the Oghuz Turks, in particular, brought their language, Oghuz—the direct ancestor of today’s Turkish language—into Anatolia during the 11th century.[20] Also during the 11th century, an early linguist of the Turkic languages, Mahmud al-Kashgari from the Kara-Khanid Khanate, published the first comprehensive Turkic language dictionary and map of the geographical distribution of Turkic speakers in the Compendium of the Turkic Dialects (Ottoman Turkish: Divânü Lügati’t-Türk).[21]

Ottoman Turkish

The 15th century Book of Dede Korkut

Following the adoption of Islam c. 950 by the Kara-Khanid Khanate and the Seljuq Turks, who are both regarded as the ethnic and cultural ancestors of the Ottomans, the administrative language of these states acquired a large collection of loanwords from Arabic and Persian. Turkish literature during the Ottoman period, particularly Divan poetry, was heavily influenced by Persian, including the adoption of poetic meters and a great quantity of imported words. The literary and official language during the Ottoman Empire period (c. 1299–1922) is termed Ottoman Turkish, which was a mixture of Turkish, Persian, and Arabic that differed considerably and was largely unintelligible to the period’s everyday Turkish. The everyday Turkish, known as kaba Türkçe or “rough Turkish”, spoken by the less-educated lower and also rural members of society, contained a higher percentage of native vocabulary and served as basis for the modern Turkish language.[22]

Language reform and modern Turkish

After the foundation of the modern state of Turkey and the script reform, the Turkish Language Association (TDK) was established in 1932 under the patronage of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, with the aim of conducting research on Turkish. One of the tasks of the newly established association was to initiate a language reform to replace loanwords of Arabic and Persian origin with Turkish equivalents.[23] By banning the usage of imported words in the press, the association succeeded in removing several hundred foreign words from the language. While most of the words introduced to the language by the TDK were newly derived from Turkic roots, it also opted for reviving Old Turkish words which had not been used for centuries.[24]

Owing to this sudden change in the language, older and younger people in Turkey started to differ in their vocabularies. While the generations born before the 1940s tend to use the older terms of Arabic or Persian origin, the younger generations favor new expressions. It is considered particularly ironic that Atatürk himself, in his lengthy speech to the new Parliament in 1927, used a style of Ottoman which sounded so alien to later listeners that it had to be “translated” three times into modern Turkish: first in 1963, again in 1986, and most recently in 1995.[25]

The past few decades have seen the continuing work of the TDK to coin new Turkish words to express new concepts and technologies as they enter the language, mostly from English. Many of these new words, particularly information technology terms, have received widespread acceptance. However, the TDK is occasionally criticized for coining words which sound contrived and artificial. Some earlier changes—such as bölem to replace fırka, “political party”—also failed to meet with popular approval (fırka has been replaced by the French loanword parti). Some words restored from Old Turkic have taken on specialized meanings; for example betik (originally meaning “book”) is now used to mean “script” in computer science.[26]

Some examples of modern Turkish words and the old loanwords are:

| Ottoman Turkish | Modern Turkish | English translation | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| müselles | üçgen | triangle | Compound of the noun üç the suffix -gen |

| tayyare | uçak | aeroplane | Derived from the verb uçmak (“to fly”). The word was first proposed to mean “airport”. |

| nispet | oran | ratio | The old word is still used in the language today together with the new one. The modern word is from the Old Turkic verb or- (to cut). |

| şimal | kuzey | north | Derived from the Old Turkic noun kuz (“cold and dark place”, “shadow”). The word is restored from Middle Turkic usage.[27] |

| teşrinievvel | ekim | October | The noun ekim means “the action of planting”, referring to the planting of cereal seeds in autumn, which is widespread in Turkey |

Geographic distribution

Turkish is natively spoken by the Turkish people in Turkey and by the Turkish diaspora in some 30 other countries. Turkish language is mutually intelligible with Azerbaijani and other Turkic languages. In particular, Turkish-speaking minorities exist in countries that formerly (in whole or part) belonged to the Ottoman Empire, such as Iraq[28], Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece (primarily in Western Thrace), the Republic of North Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia. More than two million Turkish speakers live in Germany; and there are significant Turkish-speaking communities in the United States, France, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.[29] Due to the cultural assimilation of Turkish immigrants in host countries, not all ethnic members of the diaspora speak the language with native fluency.[30]

In 2005 93% of the population of Turkey were native speakers of Turkish,[31] about 67 million at the time, with Kurdish languages making up most of the remainder.[32]

Official status

Bilingual sign, Turkish (top) and Arabic (bottom), at a Turkmen village in Kirkuk Governorate, Iraq.

Turkish is the official language of Turkey and is one of the official languages of Cyprus. Turkish has official status in 38 municipalities in Kosovo, including Mamusha,[33][34], two in the Republic of North Macedonia and in Kirkuk Governorate in Iraq.[35][36]

In Turkey, the regulatory body for Turkish is the Turkish Language Association (Türk Dil Kurumu or TDK), which was founded in 1932 under the name Türk Dili Tetkik Cemiyeti (“Society for Research on the Turkish Language”). The Turkish Language Association was influenced by the ideology of linguistic purism: indeed one of its primary tasks was the replacement of loanwords and of foreign grammatical constructions with equivalents of Turkish origin.[37] These changes, together with the adoption of the new Turkish alphabet in 1928, shaped the modern Turkish language spoken today. The TDK became an independent body in 1951, with the lifting of the requirement that it should be presided over by the Minister of Education. This status continued until August 1983, when it was again made into a governmental body in the constitution of 1982, following the military coup d’état of 1980.[24]

Dialects

Map of the main subgroups of Turkish dialects across Southeast Europe and the Middle East.

Modern standard Turkish is based on the dialect of Istanbul.[38] This “Istanbul Turkish” (İstanbul Türkçesi) constitutes the model of written and spoken Turkish, as recommended by Ziya Gökalp, Ömer Seyfettin and others.[39]

Dialectal variation persists, in spite of the levelling influence of the standard used in mass media and in the Turkish education system since the 1930s.[40] Academic researchers from Turkey often refer to Turkish dialects as ağız or şive, leading to an ambiguity with the linguistic concept of accent, which is also covered with these words. Several universities, as well as a dedicated work-group of the Turkish Language Association, carry out projects investigating Turkish dialects. As of 2002 work continued on the compilation and publication of their research as a comprehensive dialect-atlas of the Turkish language.[41][42]

Some immigrants to Turkey from Rumelia speak Rumelice, which includes the distinct dialects of Ludogorie, Dinler, and Adakale, which show the influence of the theoretized Balkan sprachbund. Kıbrıs Türkçesi is the name for Cypriot Turkish and is spoken by the Turkish Cypriots. Edirne is the dialect of Edirne. Ege is spoken in the Aegean region, with its usage extending to Antalya. The nomadic Yörüks of the Mediterranean Region of Turkey also have their own dialect of Turkish.[43] This group is not to be confused with the Yuruk nomads of Macedonia, Greece, and European Turkey, who speak Balkan Gagauz Turkish.

Güneydoğu is spoken in the southeast, to the east of Mersin. Doğu, a dialect in the Eastern Anatolia Region, has a dialect continuum. The Meskhetian Turks who live in Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Russia as well as in several Central Asian countries, also speak an Eastern Anatolian dialect of Turkish, originating in the areas of Kars, Ardahan, and Artvin and sharing similarities with Azerbaijani, the language of Azerbaijan.[44]

The Central Anatolia Region speaks Orta Anadolu. Karadeniz, spoken in the Eastern Black Sea Region and represented primarily by the Trabzon dialect, exhibits substratum influence from Greek in phonology and syntax;[45] it is also known as Laz dialect (not to be confused with the Laz language). Kastamonu is spoken in Kastamonu and its surrounding areas. Karamanli Turkish is spoken in Greece, where it is called Kαραμανλήδικα. It is the literary standard for the Karamanlides.[46]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | (c) | k | |

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | (ɟ) | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | h | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ||||

| Approximant | (ɫ) | l | j | (ɰ) | |||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||

At least one source claims Turkish consonants are larengially specified three-way fortis-lenis (aspirated/neutral/voiced) like Armenian.[48]

The phoneme that is usually referred to as yumuşak g (“soft g”), written ⟨ğ⟩ in Turkish orthography, represents a vowel sequence or a rather weak bilabial approximant between rounded vowels, a weak palatal approximant between unrounded front vowels, and a vowel sequence elsewhere. It never occurs at the beginning of a word or a syllable, but always follows a vowel. When word-final or preceding another consonant, it lengthens the preceding vowel.[49]

In native Turkic words, the sounds [c], [ɟ], and [l] are in complementary distribution with [k], [ɡ], and [ɫ]; the former set occurs adjacent to front vowels and the latter adjacent to back vowels. The distribution of these phonemes is often unpredictable, however, in foreign borrowings and proper nouns. In such words, [c], [ɟ], and [l] often occur with back vowels:[50] some examples are given below.

Consonant devoicing

Turkish orthography reflects final-obstruent devoicing, a form of consonant mutation whereby a voiced obstruent, such as /b d dʒ ɡ/, is devoiced to [p t tʃ k] at the end of a word or before a consonant, but retains its voicing before a vowel. In loan words, the voiced equivalent of /k/ is /g/; in native words, it is /ğ/.[51][52]

| Underlying consonant |

Devoiced form |

Underlying morpheme |

Dictionary form | Dative case / 1sg present |

Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | p | *kitab | kitap | kitaba | book (loan) |

| c | ç | *uc | uç | uca | tip |

| d | t | *bud | but | buda | thigh |

| g | k | *reng | renk | renge | color (loan) |

| ğ | k | *ekmeğ | ekmek | ekmeğe | bread |

This is analogous to languages such as German and Russian, but in the case of Turkish, the spelling is usually made to match the sound. However, in a few cases, such as ad /at/ ‘name’ (dative ada), the underlying form is retained in the spelling (cf. at /at/ ‘horse’, dative ata). Other exceptions are od ‘fire’ vs. ot ‘herb’, sac ‘sheet metal’, saç ‘hair’. Most loanwords, such as kitap above, are spelled as pronounced, but a few such as hac ‘hajj’, şad ‘happy’, and yad ‘strange(r)’ also show their underlying forms.[citation needed]

Native nouns of two or more syllables that end in /k/ in dictionary form are nearly all //ğ// in underlying form. However, most verbs and monosyllabic nouns are underlyingly //k//.[53]

Vowels

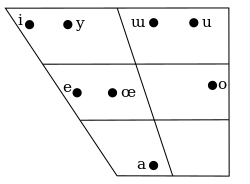

Vowels of Turkish. From Zimmer & Orgun (1999:155)

The vowels of the Turkish language are, in their alphabetical order, ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨ı⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩.[54] The Turkish vowel system can be considered as being three-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by how and where they are articulated focusing on three key features: front and back, rounded and unrounded and vowel height.[55] Vowels are classified [±back], [±round] and [±high].[56]

The only diphthongs in the language are found in loanwords and may be categorised as falling diphthongs usually analyzed as a sequence of /j/ and a vowel.[49]

Vowel harmony

| Turkish Vowel Harmony | Front Vowels | Back Vowels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |||||

| Vowel | e /e/ | i /i/ | ü /y/ | ö /œ/ | a /a/ | ı /ɯ/ | u /u/ | o /o/ |

| Twofold (Backness) | e | a | ||||||

| Fourfold (Backness + Rounding) | i | ü | ı | u | ||||

Road sign at the European end of the Bosphorus Bridge in Istanbul. (Photo taken during the 28th Istanbul Marathon in 2006)

Turkish is an agglutinative language where a series of suffixes are added to the stem word; vowel harmony is a phonological process which ensures a smooth flow, requiring the least amount of oral movement as possible. Vowel harmony can be viewed as a process of assimilation, whereby following vowels take on the characteristics of the preceding vowel.[57] It may be useful to think of Turkish vowels as two symmetrical sets: the a-undotted (a, ı, o, u) which are all back vowels, articulated at the back of the mouth; and the e-dotted (e, i, ö, ü) vowels which are articulated at the front of the mouth. The place and manner of articulation of the vowels will determine which pattern of vowel harmony a word will adopt. The pattern of vowels is shown in the table above.[58]

Grammatical affixes have “a chameleon-like quality”,[59] and obey one of the following patterns of vowel harmony:

- twofold (-e/-a):[60] the locative case suffix, for example, is -de after front vowels and -da after back vowels. The notation -de² is a convenient shorthand for this pattern.

- fourfold (-i/-ı/-ü/-u): the genitive case suffix, for example, is -in or -ın after unrounded vowels (front or back respectively); and -ün or -un after the corresponding rounded vowels. In this case, the shorthand notation -in4 is used.

Practically, the twofold pattern (also referred to as the e-type vowel harmony) means that in the environment where the vowel in the word stem is formed in the front of the mouth, the suffix will take the e-form, while if it is formed in the back it will take the a-form. The fourfold pattern (also called the i-type) accounts for rounding as well as for front/back.[57] The following examples, based on the copula -dir4 (“[it] is”), illustrate the principles of i-type vowel harmony in practice: Türkiye’dir (“it is Turkey”),[61] kapıdır (“it is the door”), but gündür (“it is the day”), paltodur (“it is the coat”).[62]

There are several exceptions to the vowel harmony rules, which can be categorised as follows:

- A few native root words such as anne (mother), elma (apple) and kardeş (brother). In these cases the suffixes harmonise with the final vowel.

- Compounds such as bu-gün (today) and baş-kent (capital). In these cases vowels are not required to harmonise between the constituent words.

- Loanwords often don’t harmonise, however, in some cases the suffixes will harmonise with the front vowel even in words that may not have a front vowel in the final syllable. Usually this occurs when the words end in a palatal [l], for example halsiz < hal + -siz “listless”, meçhuldür < meçhul + -dir “it is unknown”. However, affixes borrowed from foreign languages do not harmonise, such as -izm (ateizm “atheism”), -en (derived from French -ment as in taxmen “completely), anti- (antidemokratik “antidemocratic”).

- A few native suffixes are also invariable (or at least partially so) such as the second vowel in the bound auxiliary -abil, or in the marker -ken as well as in the imperfect suffix -yor. There are also a few derivational suffixes that do not harmonise such as -gen in uçgen (triangle) or altigen (hexagon). [55]

Some rural dialects lack some or all of these exceptions mentioned above.

The road sign in the photograph above illustrates several of these features:

- a native compound which does not obey vowel harmony: Orta+köy (“middle village”—a place name)

- a loanword also violating vowel harmony: viyadük (< French viaduc “viaduct”)

- the possessive suffix -i4 harmonizing with the final vowel (and softening the k by consonant alternation): viyadüğü[citation needed]

The rules of vowel harmony may vary by regional dialect. The dialect of Turkish spoken in the Trabzon region of northeastern Turkey follows the reduced vowel harmony of Old Anatolian Turkish, with the additional complication of two missing vowels (ü and ı), thus there is no palatal harmony. It’s likely that elün meant “your hand” in Old Anatolian. While the 2nd person singular possessive would vary between back and front vowel, -ün or -un, as in elün for “your hand” and kitabun for “your book”, the lack of ü vowel in the Trabzon dialect means -un would be used in both of these cases — elun and kitabun.[63]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2018)

|

Word-accent

Word-accent is usually on the last syllable in most words.[49] There are however, several exceptions. Exceptions include certain loanwords, particularly from Italian and Greek, as well as interjections, certain question words, adverbs (although not adjectives functioning as adverbs), and many proper names. Loanwords are usually accented on the penultimate syllable ([ɫoˈkanta] lokanta “restaurant” or [isˈcele] iskele “quay”). Proper names are usually accented on the penultimate syllable as in [isˈtanbuɫ] İstanbul, but sometimes on the antepenultimate, if the word ends in a cretic rhythm (¯ ˘ ¯ or ¯ ˘ ˘), as in [ˈaŋkaɾa] Ankara. (See Turkish phonology#Place names.)

In addition, there are certain suffixes such as -le “with” and the verbal negative particle -me-/-ma-, which place an accent on the syllable which precedes them, e.g. kitáp-la “with the book”, dé-me-mek “not to say”.[64]

In some circumstances (for example, in the second half of compound words or when verbs are preceded by an indefinite object) the accent on a word is suppressed and cannot be heard.

Syntax

Sentence groups

Turkish has two groups of sentences: verbal and nominal sentences. In the case of a verbal sentence, the predicate is a finite verb, while the predicate in nominal sentence will have either no overt verb or a verb in the form of the copula ol or y (variants of “be”). Examples of both are given below:[65]

| Sentence type | Turkish | English | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Predicate | ||

| Verbal | Necla | okula gitti | Necla went to school |

| Nominal (no verb) | Necla | öğretmen | Necla is a teacher |

| (copula) | Necla | ev-de-y-miş (hyphens delineate suffixes) | Apparently Necla is at home |

Negation

The two groups of sentences have different ways of forming negation. A nominal sentence can be negated with the addition of the word değil. For example, the sentence above would become Necla öğretmen değil (‘Necla is not a teacher’). However, the verbal sentence requires the addition of a negative suffix -me to the verb (the suffix comes after the stem but before the tense): Necla okula gitmedi (‘Necla did not go to school’).[66]

Yes/no questions

In the case of a verbal sentence, an interrogative clitic mi is added after the verb and stands alone, for example Necla okula gitti mi? (‘Did Necla go to school?’). In the case of a nominal sentence, then mi comes after the predicate but before the personal ending, so for example Necla, siz öğretmen misiniz? (‘Necla, are you [formal, plural] a teacher?’).[66]

Word order

Word order in simple Turkish sentences is generally subject–object–verb, as in Korean and Latin, but unlike English, for verbal sentences and subject-predicate for nominal sentences. However, as Turkish possesses a case-marking system, and most grammatical relations are shown using morphological markers, often the SOV structure has diminished relevance and may vary. The SOV structure may thus be considered a “pragmatic word order” of language, one that does not rely on word order for grammatical purposes.[67]

Immediately preverbal

Consider the following simple sentence which demonstrates that the focus in Turkish is on the element that immediately precedes the verb:[68]

| Word order | Focus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | AhmetAhmet | yumurta-yıegg (accusative) | yediate | unmarked: Ahmet ate the egg |

| SVO | Ahmet | yedi | yumurta-yı | the focus is on the subject: Ahmet (it was Ahmet who ate the egg) |

| OVS | Yumurta-yı | yedi | Ahmet | the focus is on the object: egg (it was an egg that Ahmet ate) |

Postpredicate

The postpredicate position signifies what is referred to as background information in Turkish- information that is assumed to be known to both the speaker and the listener, or information that is included in the context. Consider the following examples:[65]

| Sentence type | Word order | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | S-predicate | Bu ev güzelmiş (apparently this house is beautiful) | unmarked |

| Predicate-s | Güzelmiş bu ev (it is apparently beautiful, this house) | it is understood that the sentence is about this house | |

| Verbal | SOV | Bana da bir kahve getir (get me a coffee too) | unmarked |

| Bana da getir bir kahve (get me one too, a coffee) | it is understood that it is a coffee that the speaker wants |

Topic

There has been some debate among linguists whether Turkish is a subject-prominent (like English) or topic-prominent (like Japanese and Korean) language, with recent scholarship implying that it is indeed both subject and topic-prominent.[69] This has direct implications for word order as it is possible for the subject to be included in the verb-phrase in Turkish. There can be S/O inversion in sentences where the topic is of greater importance than the subject.

Grammar

Turkish is an agglutinative language and frequently uses affixes, and specifically suffixes, or endings.[70] One word can have many affixes and these can also be used to create new words, such as creating a verb from a noun, or a noun from a verbal root (see the section on Word formation). Most affixes indicate the grammatical function of the word.[71] The only native prefixes are alliterative intensifying syllables used with adjectives or adverbs: for example sımsıcak (“boiling hot” < sıcak) and masmavi (“bright blue” < mavi).[72]

The extensive use of affixes can give rise to long words, e.g. Çekoslovakyalılaştıramadıklarımızdanmışsınızcasına, meaning “In the manner of you being one of those that we apparently couldn’t manage to convert to Czechoslovakian”. While this case is contrived, long words frequently occur in normal Turkish, as in this heading of a newspaper obituary column: Bayramlaşamadıklarımız (Bayram [festival]-Recipr-Impot-Partic-Plur-PossPl1; “Those of our number with whom we cannot exchange the season’s greetings”).[73] Another example can be seen in the final word of this heading of the online Turkish Spelling Guide (İmlâ Kılavuzu): Dilde birlik, ulusal birliğin vazgeçilemezlerindendir (“Unity in language is among the indispensables [dispense-Pass-Impot-Plur-PossS3-Abl-Copula] of national unity ~ Linguistic unity is a sine qua non of national unity”).[74]

Nouns

There is no definite article in Turkish, but definiteness of the object is implied when the accusative ending is used (see below). Turkish nouns decline by taking case endings. There are six noun cases in Turkish, with all the endings following vowel harmony (shown in the table using the shorthand superscript notation. The plural marker -ler ² immediately follows the noun before any case or other affixes (e.g. köylerin “of the villages”).[citation needed]

| Case | Ending | Examples | Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| köy “village” | ağaç “tree” | |||

| Nominative | ∅ (none) | köy | ağaç | (the) village/tree |

| Genitive | -in 4 | köyün | ağacın | the village’s/tree’s of the village/tree |

| Dative | -e ² | köye | ağaca | to the village/tree |

| Accusative | -i 4 | köyü | ağacı | the village/tree |

| Ablative | -den ² | köyden | ağaçtan | from the village/tree |

| Locative | -de ² | köyde | ağaçta | in the village/on the tree |

The accusative case marker is used only for definite objects; compare (bir) ağaç gördük “we saw a tree” with ağacı gördük “we saw the tree”.[75] The plural marker -ler ² is generally not used when a class or category is meant: ağaç gördük can equally well mean “we saw trees [as we walked through the forest]”—as opposed to ağaçları gördük “we saw the trees [in question]”.[citation needed]

The declension of ağaç illustrates two important features of Turkish phonology: consonant assimilation in suffixes (ağaçtan, ağaçta) and voicing of final consonants before vowels (ağacın, ağaca, ağacı).[citation needed]

Additionally, nouns can take suffixes that assign person: for example -imiz 4, “our”. With the addition of the copula (for example -im 4, “I am”) complete sentences can be formed. The interrogative particle mi 4 immediately follows the word being questioned: köye mi? “[going] to the village?”, ağaç mı? “[is it a] tree?”.[citation needed]

| Turkish | English |

|---|---|

| ev | (the) house |

| evler | (the) houses |

| evin | your (sing.) house |

| eviniz | your (pl./formal) house |

| evim | my house |

| evimde | at my house |

| evlerinizin | of your houses |

| evlerinizden | from your houses |

| evlerinizdendi | (he/she/it) was from your houses |

| evlerinizdenmiş | (he/she/it) was (apparently/said to be) from your houses |

| Evinizdeyim. | I am at your house. |

| Evinizdeymişim. | I was (apparently) at your house. |

| Evinizde miyim? | Am I at your house? |

Personal pronouns

The Turkish personal pronouns in the nominative case are ben (1s), sen (2s), o (3s), biz (1pl), siz (2pl, or 2h), and onlar (3pl). They are declined regularly with some exceptions: benim (1s gen.); bizim (1pl gen.); bana (1s dat.); sana (2s dat.); and the oblique forms of o use the root on. All other pronouns (reflexive kendi and so on) are declined regularly.[citation needed]

Noun phrases (tamlama)

Two nouns, or groups of nouns, may be joined in either of two ways:

- definite (possessive) compound (belirtili tamlama). E.g. Türkiye’nin sesi “the voice of Turkey (radio station)”: the voice belonging to Turkey. Here the relationship is shown by the genitive ending -in4 added to the first noun; the second noun has the third-person suffix of possession -(s)i4.

- indefinite (qualifying) compound (belirtisiz tamlama). E.g. Türkiye Cumhuriyeti “Turkey-Republic[76] = the Republic of Turkey”: not the republic belonging to Turkey, but the Republic that is Turkey. Here the first noun has no ending; but the second noun has the ending -(s)i4—the same as in definite compounds.[citation needed]

The following table illustrates these principles.[77] In some cases the constituents of the compounds are themselves compounds; for clarity these subsidiary compounds are marked with [square brackets]. The suffixes involved in the linking are underlined. Note that if the second noun group already had a possessive suffix (because it is a compound by itself), no further suffix is added.

| Definite (possessive) | Indefinite (qualifier) | Complement | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| kimsenin | yanıtı | nobody’s answer | |

| “kimse” | yanıtı | the answer “nobody” | |

| Atatürk’ün | evi | Atatürk’s house | |

| Atatürk | Bulvarı | Atatürk Boulevard (named after, not belonging to Atatürk) | |

| Orhan’ın | adı | Orhan’s name | |

| “Orhan” | adı | the name “Orhan” | |

| r | sessizi | the consonant r | |

| [r sessizi]nin | söylenişi | pronunciation of the consonant r | |

| Türk | [Dil Kurumu] | Turkish language-association | |

| [Türk Dili] | Dergisi | Turkish-language magazine | |

| Ford | [aile arabası] | Ford family car | |

| Ford’un | [aile arabası] | (Mr) Ford’s family car | |

| [Ford ailesi]nin | arabası | the Ford family’s car[78] | |

| Ankara | [Kız Lisesi][79] | Ankara Girls’ School | |

| [yıl sonu] | sınavları | year-end examinations | |

| Bulgaristan’ın | [İstanbul Başkonsolosluğu] | the Istanbul Consulate-General of Bulgaria (located in Istanbul, but belonging to Bulgaria) | |

| [ [İstanbul Üniversitesi] [Edebiyat Fakültesi] ] | [ [Türk Edebiyatı] Profesörü] | Professor of Turkish Literature in the Faculty of Literature of the University of Istanbul | |

| ne oldum | delisi | “what-have-I-become!”[80] madman = parvenu who gives himself airs |

As the last example shows, the qualifying expression may be a substantival sentence rather than a noun or noun group.[81]

There is a third way of linking the nouns where both nouns take no suffixes (takısız tamlama). However, in this case the first noun acts as an adjective,[82] e.g. Demir kapı (iron gate), elma yanak (“apple cheek”, i.e. red cheek), kömür göz (“coal eye”, i.e. black eye) :

Adjectives

Turkish adjectives are not declined. However most adjectives can also be used as nouns, in which case they are declined: e.g. güzel (“beautiful”) → güzeller (“(the) beautiful ones / people”). Used attributively, adjectives precede the nouns they modify. The adjectives var (“existent”) and yok (“non-existent“) are used in many cases where English would use “there is” or “have”, e.g. süt yok (“there is no milk”, lit. “(the) milk (is) non-existent”); the construction “noun 1-GEN noun 2-POSS var/yok” can be translated “noun 1 has/doesn’t have noun 2“; imparatorun elbisesi yok “the emperor has no clothes” (“(the) emperor-of clothes-his non-existent”); kedimin ayakkabıları yoktu (“my cat had no shoes”, lit. “cat-my–of shoe-plur.–its non-existent-past tense“).[citation needed]

Verbs

Turkish verbs indicate person. They can be made negative, potential (“can”), or impotential (“cannot”). Furthermore, Turkish verbs show tense (present, past, future, and aorist), mood (conditional, imperative, inferential, necessitative, and optative), and aspect. Negation is expressed by the infix -me²- immediately following the stem.

| Turkish | English |

|---|---|

| gel- | (to) come |

| gelebil- | (to) be able to come |

| gelme- | not (to) come |

| geleme- | (to) be unable to come |

| gelememiş | Apparently (s)he couldn’t come |

| gelebilecek | (s)he’ll be able to come |

| gelmeyebilir | (s)he may (possibly) not come |

| gelebilirsen | if thou can come |

| gelinir | (passive) one comes, people come |

| gelebilmeliydin | thou shouldst have been able to come |

| gelebilseydin | if thou could have come |

| gelmeliydin | thou shouldst have come |

Verb tenses

(Note. For the sake of simplicity the term “tense” is used here throughout, although for some forms “aspect” or “mood” might be more appropriate.) There are 9 simple and 20 compound tenses in Turkish. 9 simple tenses are simple past (di’li geçmiş), inferential past (miş’li geçmiş), present continuous, simple present (aorist), future, optative, subjunctive, necessitative (“must”) and imperative.[83] There are three groups of compound forms. Story (hikaye) is the witnessed past of the above forms (except command), rumor (rivayet) is the unwitnessed past of the above forms (except simple past and command), conditional (koşul) is the conditional form of the first five basic tenses.[84] In the example below the second person singular of the verb gitmek (“go”), stem gid-/git-, is shown.

| English of the basic form | Basic tense | Story (hikaye) | Rumor (rivayet) | Condition (koşul) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| you went | gittin | gittiydin | – | gittiysen |

| you have gone | gitmişsin | gitmiştin | gitmişmişsin | gitmişsen |

| you are going | gidiyorsun | gidiyordun | gidiyormuşsun | gidiyorsan |

| you (are wont to) go | gidersin | giderdin | gidermişsin | gidersen |

| you will go | gideceksin | gidecektin | gidecekmişsin | gideceksen |

| if only you go | gitsen | gitseydin | gitseymişsin | – |

| may you go | gidesin | gideydin | gideymişsin | – |

| you must go | gitmelisin | gitmeliydin | gitmeliymişsin | – |

| go! (imperative) | git | – | – | – |

There are also so-called combined verbs, which are created by suffixing certain verb stems (like bil or ver) to the original stem of a verb. Bil is the suffix for the sufficiency mood. It is the equivalent of the English auxiliary verbs “able to”, “can” or “may”. Ver is the suffix for the swiftness mood, kal for the perpetuity mood and yaz for the approach (“almost”) mood.[85] Thus, while gittin means “you went”, gidebildin means “you could go” and gidiverdin means “you went swiftly”. The tenses of the combined verbs are formed the same way as for simple verbs.

Attributive verbs (participles)

Turkish verbs have attributive forms, including present,[86] similar to the English present participle (with the ending -en2); future (-ecek2); indirect/inferential past (-miş4); and aorist (-er2 or -ir4).

The most important function of some of these attributive verbs is to form modifying phrases equivalent to the relative clauses found in most European languages. The subject of the verb in an -en2 form is (possibly implicitly) in the third person (he/she/it/they); this form, when used in a modifying phrase, does not change according to number. The other attributive forms used in these constructions are the future (-ecek2) and an older form (-dik4), which covers both present and past meanings.[87] These two forms take “personal endings”, which have the same form as the possessive suffixes but indicate the person and possibly number of the subject of the attributive verb; for example, yediğim means “what I eat”, yediğin means “what you eat”, and so on. The use of these “personal or relative participles” is illustrated in the following table, in which the examples are presented according to the grammatical case which would be seen in the equivalent English relative clause.[88]

| English equivalent | Example | Translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case of relative pronoun | Pronoun | Literal | Idiomatic | |

| Nominative | who, which/that | şimdi konuşan adam | “now speaking man” | the man (who is) now speaking |

| Genitive | whose (nom.) | babası şimdi konuşan adam | “father-is now speaking man” | the man whose father is now speaking |

| whose (acc.) | babasını dün gördüğüm adam | “father-is-ACC yesterday seen-my man” | the man whose father I saw yesterday | |

| at whose | resimlerine baktığımız ressam | “pictures-is-to looked-our artist” | the artist whose pictures we looked at | |

| of which | muhtarı seçildiği köy | “mayor-its been-chosen-his village” | the village of which he was elected mayor | |

| of which | muhtarı seçilmek istediği köy | the village of which he wishes to be elected mayor | ||

| Remaining cases (incl. prepositions) | whom, which | yazdığım mektup | “written-my letter” | the letter (which) I wrote |

| from which | çıktığımız kapı | “emerged-our door” | the door from which we emerged | |

| on which | geldikleri vapur | “come-their ship” | the ship they came on | |

| which + subordinate clause | yaklaştığını anladığı hapishane günleri | “approach-their-ACC understood-his prison days-its” | the prison days (which) he knew were approaching[89][90] | |

Vocabulary

Latest 2010 edition of Büyük Türkçe Sözlük (Great Turkish Dictionary), the official dictionary of the Turkish language published by Turkish Language Association, contains 616,767 words, expressions, terms and nouns.[91]

The 2005 edition of Güncel Türkçe Sözlük, the official dictionary of the Turkish language published by Turkish Language Association, contains 104,481 words, of which about 86% are Turkish and 14% are of foreign origin.[92] Among the most significant foreign contributors to Turkish vocabulary are Arabic, French, Persian, Italian, English, and Greek.[93]

Word formation

Turkish extensively uses agglutination to form new words from nouns and verbal stems. The majority of Turkish words originate from the application of derivative suffixes to a relatively small set of core vocabulary.[94]

Turkish obeys certain principles when it comes to suffixation. Most suffixes in Turkish will have more than one form, depending on the vowels and consonants in the root- vowel harmony rules will apply; consonant-initial suffixes will follow the voiced/ voiceless character of the consonant in the final unit of the root; and in the case of vowel-initial suffixes an additional consonant may be inserted if the root ends in a vowel, or the suffix may lose its initial vowel. There is also a prescribed order of affixation of suffixes- as a rule of thumb, derivative suffixes precede inflectional suffixes which are followed by clitics, as can be seen in the example set of words derived from a substantive root below:

| Turkish | Components | English | Word class |

|---|---|---|---|

| göz | göz | eye | Noun |

| gözlük | göz + -lük | eyeglasses | Noun |

| gözlükçü | göz + -lük + -çü | optician | Noun |

| gözlükçülük | göz + -lük + -çü + -lük | optician’s trade | Noun |

| gözlem | göz + -lem | observation | Noun |

| gözlemci | göz + -lem + -ci | observer | Noun |

| gözle- | göz + -le | observe | Verb (order) |

| gözlemek | göz + -le + -mek | to observe | Verb (infinitive) |

| gözetlemek | göz + -et + -le + -mek | to peep | Verb (infinitive) |

Another example, starting from a verbal root:

| Turkish | Components | English | Word class |

|---|---|---|---|

| yat- | yat- | lie down | Verb (order) |

| yatmak | yat-mak | to lie down | Verb (infinitive) |

| yatık | yat- + -(ı)k | leaning | Adjective |

| yatak | yat- + -ak | bed, place to sleep | Noun |

| yatay | yat- + -ay | horizontal | Adjective |

| yatkın | yat- + -gın | inclined to; stale (from lying too long) | Adjective |

| yatır- | yat- + -(ı)r- | lay down | Verb (order) |

| yatırmak | yat- + -(ı)r-mak | to lay down something/someone | Verb (infinitive) |

| yatırım | yat- + -(ı)r- + -(ı)m | laying down; deposit, investment | Noun |

| yatırımcı | yat- + -(ı)r- + -(ı)m + -cı | depositor, investor | Noun |

New words are also frequently formed by compounding two existing words into a new one, as in German. Compounds can be of two types- bare and (s)I. The bare compounds, both nouns and adjectives are effectively two words juxtaposed without the addition of suffixes for example the word for girlfriend kızarkadaş (kız+arkadaş) or black pepper karabiber (kara+biber). A few examples of compound words are given below:

| Turkish | English | Constituent words | Literal meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| pazartesi | Monday | pazar (“Sunday”) and ertesi (“after”) | after Sunday |

| bilgisayar | computer | bilgi (“information”) and say- (“to count”) | information counter |

| gökdelen | skyscraper | gök (“sky”) and del- (“to pierce”) | sky piercer |

| başparmak | thumb | baş (“prime”) and parmak (“finger”) | primary finger |

| önyargı | prejudice | ön (“before”) and yargı (“splitting; judgement”) | fore-judging |

However, the majority of compound words in Turkish are (s)I compounds, which means that the second word will be marked by the 3rd person possessive suffix. A few such examples are given in the table below (note vowel harmony):

| Turkish | English | Constituent words | Possessive Suffix |

|---|---|---|---|

| el çantası | handbag | el (hand) and çanta (bag) | +sı |

| masa örtüsü | tablecloth | masa (table) and örtü (cover) | +sü |

| çay bardağı | tea glass | çay (tea) and bardak (glass) | +ı (the k changes to ğ) |

Writing system

Turkish is written using a Latin alphabet introduced in 1928 by Atatürk to replace the Ottoman Turkish alphabet, a version of Perso-Arabic alphabet. The Ottoman alphabet marked only three different vowels—long ā, ū and ī—and included several redundant consonants, such as variants of z (which were distinguished in Arabic but not in Turkish). The omission of short vowels in the Arabic script was claimed to make it particularly unsuitable for Turkish, which has eight vowels.[95]

The reform of the script was an important step in the cultural reforms of the period. The task of preparing the new alphabet and selecting the necessary modifications for sounds specific to Turkish was entrusted to a Language Commission composed of prominent linguists, academics, and writers. The introduction of the new Turkish alphabet was supported by public education centers opened throughout the country, cooperation with publishing companies, and encouragement by Atatürk himself, who toured the country teaching the new letters to the public.[96] As a result, there was a dramatic increase in literacy from its original Third World levels.[97]

The Latin alphabet was applied to the Turkish language for educational purposes even before the 20th-century reform. Instances include a 1635 Latin-Albanian dictionary by Frang Bardhi, who also incorporated several sayings in the Turkish language, as an appendix to his work (e.g. alma agatsdan irak duschamas[98]—”An apple does not fall far from its tree”).

Turkish now has an alphabet suited to the sounds of the language: the spelling is largely phonemic, with one letter corresponding to each phoneme.[99] Most of the letters are used approximately as in English, the main exceptions being ⟨c⟩, which denotes [dʒ] (⟨j⟩ being used for the [ʒ] found in Persian and European loans); and the undotted ⟨ı⟩, representing [ɯ]. As in German, ⟨ö⟩ and ⟨ü⟩ represent [ø] and [y]. The letter ⟨ğ⟩, in principle, denotes [ɣ] but has the property of lengthening the preceding vowel and assimilating any subsequent vowel. The letters ⟨ş⟩ and ⟨ç⟩ represent [ʃ] and [tʃ], respectively. A circumflex is written over back vowels following ⟨k⟩, ⟨g⟩, or ⟨l⟩ when these consonants represent [c], [ɟ], and [l]—almost exclusively in Arabic and Persian loans.[100]

The Turkish alphabet consists of 29 letters (q, x, w omitted and ç, ş, ğ, ı, ö, ü added); the complete list is:

- a, b, c, ç, d, e, f, g, ğ, h, ı, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, ö, p, r, s, ş, t, u, ü, v, y, and z (Note that capital of i is İ and lowercase I is ı.)

The specifically Turkish letters and spellings described above are illustrated in this table:

| Turkish spelling | Pronunciation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Cağaloğlu | ˈdʒaːɫoːɫu | [İstanbul district] |

| çalıştığı | tʃaɫɯʃtɯˈɣɯ | where/that (s)he works/worked |

| müjde | myʒˈde | good news |

| lazım | laˈzɯm | necessary |

| mahkûm | mahˈcum | condemned |

Sample

Dostlar Beni Hatırlasın by Aşık Veysel Şatıroğlu (1894–1973), a minstrel and highly regarded poet in the Turkish folk literature tradition.

| Orthography | IPA | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Ben giderim adım kalır | bæn ɟid̪e̞ɾim äd̪ɯm käɫɯɾ | I depart, my name remains |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | d̪o̞st̪ɫäɾ be̞ni hätɯɾɫäsɯn | May friends remember me |

| Düğün olur bayram gelir | d̪yjyn o̞ɫuɾ bäjɾäm ɟe̞liɾ | There are weddings, there are feasts |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | d̪o̞st̪ɫäɾ be̞ni hätɯɾɫäsɯn | May friends remember me |

| Can kafeste durmaz uçar | d͡ʒäŋ käfe̞st̪e̞ d̪uɾmäz ut͡ʃäɾ | The soul won’t stay caged, it flies away |

| Dünya bir han konan göçer | d̪ynjä biɾ häŋ ko̞nän ɟø̞t͡ʃæɾ | The world is an inn, residents depart |

| Ay dolanır yıllar geçer | äj d̪o̞ɫänɯɾ jɯɫːäɾ ɟe̞t͡ʃæɾ | The moon wanders, years pass by |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | d̪o̞st̪ɫäɾ be̞ni hätɯɾɫäsɯn | May friends remember me |

| Can bedenden ayrılacak | d͡ʒän be̞d̪ænd̪æn äjɾɯɫäd͡ʒäk | The soul will leave the body |

| Tütmez baca yanmaz ocak | t̪yt̪mæz bäd͡ʒä jänmäz o̞d͡ʒäk | The chimney won’t smoke, furnace won’t burn |

| Selam olsun kucak kucak | se̞läːm o̞ɫsuŋ kud͡ʒäk kud͡ʒäk | Goodbye goodbye to you all |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | d̪o̞st̪ɫäɾ be̞ni hätɯɾɫäsɯn | May friends remember me |

| Açar solar türlü çiçek | ät͡ʃäɾ so̞läɾ t̪yɾly t͡ʃit͡ʃe̞c | Various flowers bloom and fade |

| Kimler gülmüş kim gülecek | cimlæɾ ɟylmyʃ cim ɟyle̞d͡ʒe̞c | Someone laughed, someone will laugh |

| Murat yalan ölüm gerçek | muɾät jäɫän ø̞lym ɟæɾt͡ʃe̞c | Wishes are lies, death is real |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | d̪o̞st̪ɫäɾ be̞ni hätɯɾɫäsɯn | May friends remember me |

| Gün ikindi akşam olur | ɟyn icindi äkʃäm o̞ɫuɾ | Morning and afternoon turn to night |

| Gör ki başa neler gelir | ɟø̞ɾ ci bäʃä ne̞læɾ ɟe̞liɾ | And many things happen to a person anyway |

| Veysel gider adı kalır | ʋe̞jsæl ɟidæɾ äd̪ɯ käɫɯɾ | Veysel departs, his name remains |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | d̪o̞st̪ɫäɾ be̞ni hätɯɾɫäsɯn | May friends remember me |

Whistled language

In the Turkish province of Giresun, the locals in the village of Kuşköy have communicated using a whistled version of Turkish for over 400 years. The region consists of a series of deep valleys and the unusual mode of communication allows for conversation over distances of up to 5 kilometres. Turkish authorities estimate that there are still around 10,000 people using the whistled language. However, in 2011 UNESCO found whistling Turkish to be a dying language and included it in its intangible cultural heritage list. Since then the local education directorate has introduced it as a course in schools in the region, hoping to revive its use.

A study was conducted by a German scientist of Turkish origin Onur Güntürkün at Ruhr University, observing 31 “speakers” of kuş dili (“bird’s tongue”) from Kuşköy, and he found that the whistled language mirrored the lexical and syntactical structure of Turkish language.[101]

Turkish computer keyboard

Turkish language uses two standardised keyboard layouts, known as Turkish Q (QWERTY) and Turkish F, with Turkish Q being the most common.