Amino acid

Jump to navigationJump to search

Amino acids are organic compounds (molecules) that contain amine (–NH2) and carboxyl (–COOH) functional groups, along with a side chain (R group) specific to each amino acid.[1][2] The key elements of an amino acid are carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N), although other elements are found in the side chains of certain amino acids. About 500 naturally occurring amino acids are known (though only 20 appear in the genetic code) and can be classified in many ways.[3] They can be classified according to the core structural functional groups’ locations as alpha- (α-), beta- (β-), gamma- (γ-) or delta- (δ-) amino acids; other categories relate to polarity, pH level, and side chain group type (aliphatic, acyclic, aromatic, containing hydroxyl or sulfur, etc.). In the form of proteins, amino acid residues form the second-largest component (water is the largest) of human muscles and other tissues.[4] Beyond their role as residues in proteins, amino acids participate in a number of processes such as neurotransmitter transport and biosynthesis.

In biochemistry, amino acids which have the amine group attached to the (alpha-) carbon atom next to the carboxyl group have particular importance. They are known as 2-, alpha-, or α-amino acids (generic formula H2NCHRCOOH in most cases,[a] where R is an organic substituent known as a “side chain“);[5] often the term “amino acid” is used to refer specifically to these. They include the 22 proteinogenic (“protein-building”) amino acids,[6][7][8] which combine into peptide chains (“polypeptides”) to form the building blocks of a vast array of proteins.[9] These are all L–stereoisomers (“left-handed” isomers), although a few D-amino acids (“right-handed”) occur in bacterial envelopes, as a neuromodulator (D–serine), and in some antibiotics.[10]

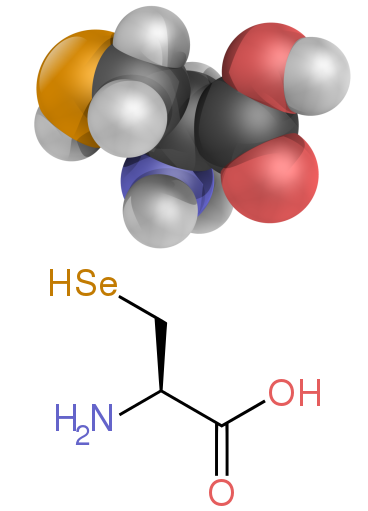

Twenty of the proteinogenic amino acids are encoded directly by triplet codons in the genetic code and are known as “standard” amino acids. The other two (“nonstandard” or “non-canonical”) are selenocysteine (present in many prokaryotes as well as most eukaryotes, but not coded directly by DNA), and pyrrolysine (found only in some archaea and one bacterium). Pyrrolysine and selenocysteine are encoded via variant codons; for example, selenocysteine is encoded by stop codon and SECIS element.[11][12][13] N-formylmethionine (which is often the initial amino acid of proteins in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts) is generally considered as a form of methionine rather than as a separate proteinogenic amino acid. Codon–tRNA combinations not found in nature can also be used to “expand” the genetic code and form novel proteins known as alloproteins incorporating non-proteinogenic amino acids.[14][15][16]

Many important proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids have biological functions. For example, in the human brain, glutamate (standard glutamic acid) and gamma-aminobutyric acid (“GABA”, nonstandard gamma-amino acid) are, respectively, the main excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters.[17] Hydroxyproline, a major component of the connective tissue collagen, is synthesised from proline. Glycine is a biosynthetic precursor to porphyrins used in red blood cells. Carnitine is used in lipid transport.

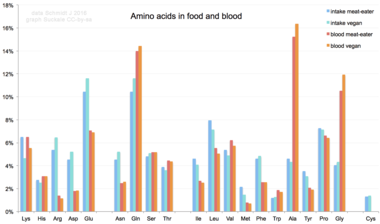

Nine proteinogenic amino acids are called “essential” for humans because they cannot be produced from other compounds by the human body and so must be taken in as food. Others may be conditionally essential for certain ages or medical conditions. Essential amino acids may also differ between species.[b]

Because of their biological significance, amino acids are important in nutrition and are commonly used in nutritional supplements, fertilizers, feed, and food technology. Industrial uses include the production of drugs, biodegradable plastics, and chiral catalysts.

History[edit]

The first few amino acids were discovered in the early 19th century.[18][19] In 1806, French chemists Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin and Pierre Jean Robiquet isolated a compound in asparagus that was subsequently named asparagine, the first amino acid to be discovered.[20][21] Cystine was discovered in 1810,[22] although its monomer, cysteine, remained undiscovered until 1884.[21][23] Glycine and leucine were discovered in 1820.[24] The last of the 20 common amino acids to be discovered was threonine in 1935 by William Cumming Rose, who also determined the essential amino acids and established the minimum daily requirements of all amino acids for optimal growth.[25][26]

The unity of the chemical category was recognized by Wurtz in 1865, but he gave no particular name to it.[27] The first use of the term “amino acid” in the English language dates from 1898,[28] while the German term, Aminosäure, was used earlier.[29] Proteins were found to yield amino acids after enzymatic digestion or acid hydrolysis. In 1902, Emil Fischer and Franz Hofmeister independently proposed that proteins are formed from many amino acids, whereby bonds are formed between the amino group of one amino acid with the carboxyl group of another, resulting in a linear structure that Fischer termed “peptide“.[30]

General structure[edit]

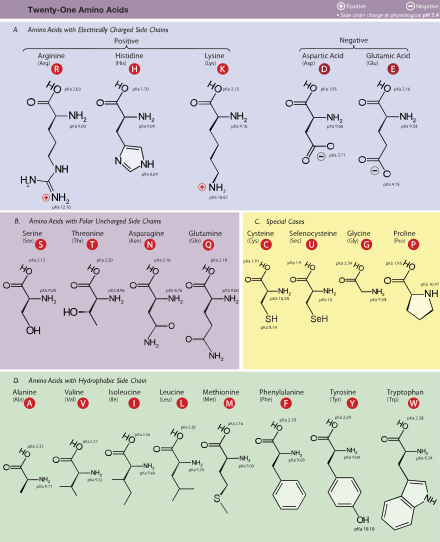

The 21 proteinogenic α-amino acids found in eukaryotes, grouped according to their side chains’ pKa values and charges carried at physiological pH (7.4)

In the structure shown at the top of the page, R represents a side chain specific to each amino acid. The carbon atom next to the carboxyl group is called the α–carbon. Amino acids containing an amino group bonded directly to the alpha carbon are referred to as alpha amino acids.[31] These include amino acids such as proline which contain secondary amines, which used to be often referred to as “imino acids”.[32][33][34]

Isomerism[edit]

Alpha amino acids are the most common form found in nature, but only when occurring in the L-isomer. The alpha carbon is a chiral carbon atom, with the exception of glycine, which has two indistinguishable hydrogen atoms on the alpha carbon.[35] Therefore, all alpha amino acids but glycine can exist in either of two enantiomers, called L or D amino acids (relative configuration), which are mirror images of each other (see also Chirality). While L-amino acids represent all of the amino acids found in proteins during translation in the ribosome, D-amino acids are found in some proteins produced by enzyme after translation and transportation to the endoplasmic reticulum, as in exotic sea-dwelling organisms such as cone snails.[36] They are also abundant components of the peptidoglycan cell walls of bacteria,[37] and D-serine may act as a neurotransmitter in the brain.[38] D-amino acids are used in racemic crystallography to create centrosymmetric crystals, which (depending on the protein) may allow for easier and more robust protein structure determination.[39] The L and D convention for amino acid configuration refers not to the optical activity of the amino acid itself but rather to the optical activity of the isomer of glyceraldehyde from which that amino acid can, in theory, be synthesized (D-glyceraldehyde is dextrorotatory; L-glyceraldehyde is levorotatory). In alternative fashion, the (S) and (R) designators are used to indicate the absolute configuration. Almost all of the amino acids in proteins are (S) at the α carbon, with cysteine being (R) and glycine non-chiral.[40] Cysteine has its side chain in the same geometric location as the other amino acids, but the R/S terminology is reversed because sulfur has higher atomic number compared to the carboxyl oxygen which gives the side chain a higher priority by the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog rules, whereas the atoms in most other side chains give them lower priority compared to the carboxyl group.[41]

Side chains[edit]

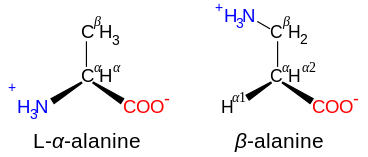

Amino acids are designated as α- when the nitrogen atom is attached to the carbon atom adjacent to the carboxyl group: in this case the compound contains the substructure N–C–CO2. Amino acids with the sub-structure N–C–C–CO2 are classified as β- amino acids. γ-Amino acids contain the substructure N–C–C–C–CO2, and so on.[42]

Amino acids are usually classified by the properties of their side chain into four groups. The side chain can make an amino acid a weak acid or a weak base, and a hydrophile if the side chain is polar or a hydrophobe if it is nonpolar.[35] The phrase “branched-chain amino acids” or BCAA refers to the amino acids having aliphatic side chains that are linear; these are leucine, isoleucine, and valine. Proline is the only proteinogenic amino acid whose side-group links to the α-amino group and, thus, is also the only proteinogenic amino acid containing a secondary amine at this position.[35] In chemical terms, proline is, therefore, an imino acid, since it lacks a primary amino group,[43] although it is still classed as an amino acid in the current biochemical nomenclature[44] and may also be called an “N-alkylated alpha-amino acid”.[45]

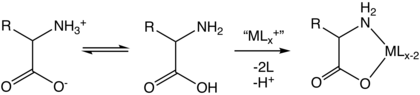

Zwitterions[edit]

In aqueous solution amino acids exist in two forms (as illustrated at the right), the molecular form and the zwitterion form in equilibrium with each other. The two forms coexist over the pH range pK1 − 2 to pK2 + 2, which for glycine is pH 0–12. The ratio of the concentrations of the two isomers is independent of pH. The value of this ratio cannot be determined experimentally.

Because all amino acids contain amine and carboxylic acid functional groups, they are amphiprotic.[35] At pH = pK1 (approximately 2.2) there will be equal concentration of the species NH+

3CH(R)CO

2H and NH+

3CH(R)CO−

2 and at pH = pK2 (approximately 10) there will be equal concentration of the species NH+

3CH(R)CO−

2 and NH

2CH(R)CO−

2. It follows that the neutral molecule and the zwitterion are effectively the only species present at biological pH.[46]

It is generally assumed that the concentration of the zwitterion is much greater than the concentration of the neutral molecule on the basis of comparisons with the known pK values of amines and carboxylic acids.

Isoelectric point[edit]

Composite of titration curves of twenty proteinogenic amino acids grouped by side chain category

At pH values between the two pKa values, the zwitterion predominates, but coexists in dynamic equilibrium with small amounts of net negative and net positive ions. At the exact midpoint between the two pKa values, the trace amount of net negative and trace of net positive ions exactly balance, so that average net charge of all forms present is zero.[47] This pH is known as the isoelectric point pI, so pI = 1/2(pKa1 + pKa2). For amino acids with charged side chains, the pKa of the side chain is involved. Thus for aspartate or glutamate with negative side chains, pI = 1/2(pKa1 + pKa(R)), where pKa(R) is the side chain pKa. Cysteine also has potentially negative side chain with pKa(R) = 8.14, so pI should be calculated as for aspartate and glutamate, even though the side chain is not significantly charged at physiological pH. For histidine, lysine, and arginine with positive side chains, pI = 1/2(pKa(R) + pKa2). Amino acids have zero mobility in electrophoresis at their isoelectric point, although this behaviour is more usually exploited for peptides and proteins than single amino acids. Zwitterions have minimum solubility at their isoelectric point, and some amino acids (in particular, with nonpolar side chains) can be isolated by precipitation from water by adjusting the pH to the required isoelectric point.

Occurrence and functions in biochemistry[edit]

Proteinogenic amino acids[edit]

Amino acids are the structural units (monomers) that make up proteins. They join together to form short polymer chains called peptides or longer chains called either polypeptides or proteins. These polymers are linear and unbranched, with each amino acid within the chain attached to two neighboring amino acids. The process of making proteins encoded by DNA/RNA genetic material is called translation and involves the step-by-step addition of amino acids to a growing protein chain by a ribozyme that is called a ribosome.[48] The order in which the amino acids are added is read through the genetic code from an mRNA template, which is an RNA copy of one of the organism’s genes.

Twenty-two amino acids are naturally incorporated into polypeptides and are called proteinogenic or natural amino acids.[35] Of these, 20 are encoded by the universal genetic code. The remaining 2, selenocysteine and pyrrolysine, are incorporated into proteins by unique synthetic mechanisms. Selenocysteine is incorporated when the mRNA being translated includes a SECIS element, which causes the UGA codon to encode selenocysteine instead of a stop codon.[49] Pyrrolysine is used by some methanogenic archaea in enzymes that they use to produce methane. It is coded for with the codon UAG, which is normally a stop codon in other organisms.[50] This UAG codon is followed by a PYLIS downstream sequence.[51]

Non-proteinogenic amino acids[edit]

Aside from the 22 proteinogenic amino acids, many non-proteinogenic amino acids are known. Those either are not found in proteins (for example carnitine, GABA, levothyroxine) or are not produced directly and in isolation by standard cellular machinery (for example, hydroxyproline and selenomethionine).

Non-proteinogenic amino acids that are found in proteins are formed by post-translational modification, which is modification after translation during protein synthesis. These modifications are often essential for the function or regulation of a protein. For example, the carboxylation of glutamate allows for better binding of calcium cations,[52] and collagen contains hydroxyproline, generated by hydroxylation of proline.[53] Another example is the formation of hypusine in the translation initiation factor EIF5A, through modification of a lysine residue.[54] Such modifications can also determine the localization of the protein, e.g., the addition of long hydrophobic groups can cause a protein to bind to a phospholipid membrane.[55]

Some non-proteinogenic amino acids are not found in proteins. Examples include 2-aminoisobutyric acid and the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid. Non-proteinogenic amino acids often occur as intermediates in the metabolic pathways for standard amino acids – for example, ornithine and citrulline occur in the urea cycle, part of amino acid catabolism (see below).[56] A rare exception to the dominance of α-amino acids in biology is the β-amino acid beta alanine (3-aminopropanoic acid), which is used in plants and microorganisms in the synthesis of pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), a component of coenzyme A.[57]

D-Amino acid natural abundance[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. (July 2019)

|

Although D-isomers are uncommon in live organisms, gramicidin is a polypeptide made up from mixture of D– and L-amino acids.[58] Other compounds containing D-amino acids are tyrocidine and valinomycin. These compounds disrupt bacterial cell walls, particularly in Gram-positive bacteria. As of 2011, only 837 D-amino acids were found in the Swiss-Prot database out of a total of 187 million amino acids analysed.[59]

Nonstandard amino acids[edit]

The 20 amino acids that are encoded directly by the codons of the universal genetic code are called standard or canonical amino acids. A modified form of methionine (N-formylmethionine) is often incorporated in place of methionine as the initial amino acid of proteins in bacteria, mitochondria and chloroplasts. Other amino acids are called nonstandard or non-canonical. Most of the nonstandard amino acids are also non-proteinogenic (i.e. they cannot be incorporated into proteins during translation), but two of them are proteinogenic, as they can be incorporated translationally into proteins by exploiting information not encoded in the universal genetic code.

The two nonstandard proteinogenic amino acids are selenocysteine (present in many non-eukaryotes as well as most eukaryotes, but not coded directly by DNA) and pyrrolysine (found only in some archaea and one bacterium). The incorporation of these nonstandard amino acids is rare. For example, 25 human proteins include selenocysteine in their primary structure,[60] and the structurally characterized enzymes (selenoenzymes) employ selenocysteine as the catalytic moiety in their active sites.[61] Pyrrolysine and selenocysteine are encoded via variant codons. For example, selenocysteine is encoded by stop codon and SECIS element.[11][12][13]

In human nutrition[edit]

When taken up into the human body from the diet, the 20 standard amino acids either are used to synthesize proteins, other biomolecules, or are oxidized to urea and carbon dioxide as a source of energy.[62] The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase; the amino group is then fed into the urea cycle. The other product of transamidation is a keto acid that enters the citric acid cycle.[63] Glucogenic amino acids can also be converted into glucose, through gluconeogenesis.[64] Of the 20 standard amino acids, nine (His, Ile, Leu, Lys, Met, Phe, Thr, Trp and Val) are called essential amino acids because the human body cannot synthesize them from other compounds at the level needed for normal growth, so they must be obtained from food.[65][66][67] In addition, cysteine, tyrosine, and arginine are considered semiessential amino acids, and taurine a semiessential aminosulfonic acid in children. The metabolic pathways that synthesize these monomers are not fully developed.[68][69] The amounts required also depend on the age and health of the individual, so it is hard to make general statements about the dietary requirement for some amino acids. Dietary exposure to the nonstandard amino acid BMAA has been linked to human neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS.[70][71]

Non-protein functions[edit]

|

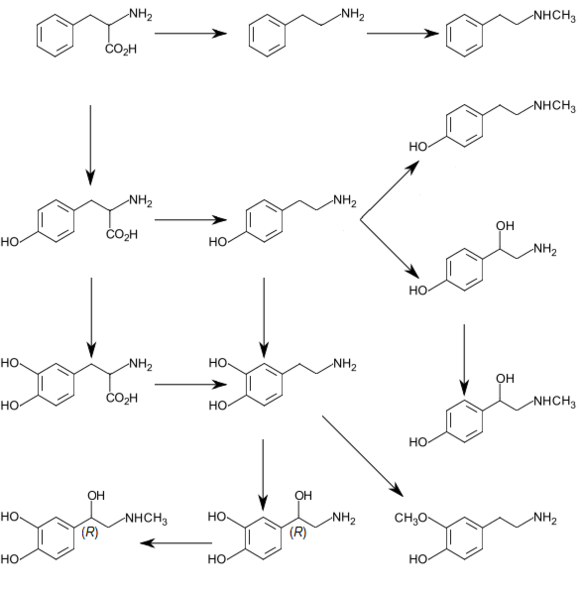

Catecholamines and trace amines are synthesized from phenylalanine and tyrosine in humans. |

In humans, non-protein amino acids also have important roles as metabolic intermediates, such as in the biosynthesis of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Many amino acids are used to synthesize other molecules, for example:

- Tryptophan is a precursor of the neurotransmitter serotonin.[78]

- Tyrosine (and its precursor phenylalanine) are precursors of the catecholamine neurotransmitters dopamine, epinephrine and norepinephrine and various trace amines.

- Phenylalanine is a precursor of phenethylamine and tyrosine in humans. In plants, it is a precursor of various phenylpropanoids, which are important in plant metabolism.

- Glycine is a precursor of porphyrins such as heme.[79]

- Arginine is a precursor of nitric oxide.[80]

- Ornithine and S-adenosylmethionine are precursors of polyamines.[81]

- Aspartate, glycine, and glutamine are precursors of nucleotides.[82] However, not all of the functions of other abundant nonstandard amino acids are known.

Some nonstandard amino acids are used as defenses against herbivores in plants.[83] For example, canavanine is an analogue of arginine that is found in many legumes,[84] and in particularly large amounts in Canavalia gladiata (sword bean).[85] This amino acid protects the plants from predators such as insects and can cause illness in people if some types of legumes are eaten without processing.[86] The non-protein amino acid mimosine is found in other species of legume, in particular Leucaena leucocephala.[87] This compound is an analogue of tyrosine and can poison animals that graze on these plants.

Uses in industry[edit]

Amino acids are used for a variety of applications in industry, but their main use is as additives to animal feed. This is necessary, since many of the bulk components of these feeds, such as soybeans, either have low levels or lack some of the essential amino acids: lysine, methionine, threonine, and tryptophan are most important in the production of these feeds.[88] In this industry, amino acids are also used to chelate metal cations in order to improve the absorption of minerals from supplements, which may be required to improve the health or production of these animals.[89]

The food industry is also a major consumer of amino acids, in particular, glutamic acid, which is used as a flavor enhancer,[90] and aspartame (aspartylphenylalanine 1-methyl ester) as a low-calorie artificial sweetener.[91] Similar technology to that used for animal nutrition is employed in the human nutrition industry to alleviate symptoms of mineral deficiencies, such as anemia, by improving mineral absorption and reducing negative side effects from inorganic mineral supplementation.[92]

The chelating ability of amino acids has been used in fertilizers for agriculture to facilitate the delivery of minerals to plants in order to correct mineral deficiencies, such as iron chlorosis. These fertilizers are also used to prevent deficiencies from occurring and improving the overall health of the plants.[93] The remaining production of amino acids is used in the synthesis of drugs and cosmetics.[88]

Similarly, some amino acids derivatives are used in pharmaceutical industry. They include 5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan) used for experimental treatment of depression,[94] L-DOPA (L-dihydroxyphenylalanine) for Parkinson’s treatment,[95] and eflornithine drug that inhibits ornithine decarboxylase and used in the treatment of sleeping sickness.[96]

Expanded genetic code[edit]

Since 2001, 40 non-natural amino acids have been added into protein by creating a unique codon (recoding) and a corresponding transfer-RNA:aminoacyl – tRNA-synthetase pair to encode it with diverse physicochemical and biological properties in order to be used as a tool to exploring protein structure and function or to create novel or enhanced proteins.[14][15]

Nullomers[edit]

Nullomers are codons that in theory code for an amino acid, however in nature there is a selective bias against using this codon in favor of another, for example bacteria prefer to use CGA instead of AGA to code for arginine.[97] This creates some sequences that do not appear in the genome. This characteristic can be taken advantage of and used to create new selective cancer-fighting drugs[98] and to prevent cross-contamination of DNA samples from crime-scene investigations.[99]

Chemical building blocks[edit]

Amino acids are important as low-cost feedstocks. These compounds are used in chiral pool synthesis as enantiomerically pure building blocks.[100]

Amino acids have been investigated as precursors chiral catalysts, such as for asymmetric hydrogenation reactions, although no commercial applications exist.[101]

Biodegradable plastics[edit]

Amino acids have been considered as components of biodegradable polymers, which have applications as environmentally friendly packaging and in medicine in drug delivery and the construction of prosthetic implants.[102] An interesting example of such materials is polyaspartate, a water-soluble biodegradable polymer that may have applications in disposable diapers and agriculture.[103] Due to its solubility and ability to chelate metal ions, polyaspartate is also being used as a biodegradeable antiscaling agent and a corrosion inhibitor.[104][105] In addition, the aromatic amino acid tyrosine has been considered as a possible replacement for phenols such as bisphenol A in the manufacture of polycarbonates.[106]

Synthesis[edit]

Chemical synthesis[edit]

The commercial production of amino acids usually relies on mutant bacteria that overproduce individual amino acids using glucose as a carbon source. Some amino acids are produced by enzymatic conversions of synthetic intermediates. 2-Aminothiazoline-4-carboxylic acid is an intermediate in one industrial synthesis of L-cysteine for example. Aspartic acid is produced by the addition of ammonia to fumarate using a lyase.[107]

Biosynthesis[edit]

In plants, nitrogen is first assimilated into organic compounds in the form of glutamate, formed from alpha-ketoglutarate and ammonia in the mitochondrion. For other amino acids, plants use transaminases to move the amino group from glutamate to another alpha-keto acid. For example, aspartate aminotransferase converts glutamate and oxaloacetate to alpha-ketoglutarate and aspartate.[108] Other organisms use transaminases for amino acid synthesis, too.

Nonstandard amino acids are usually formed through modifications to standard amino acids. For example, homocysteine is formed through the transsulfuration pathway or by the demethylation of methionine via the intermediate metabolite S-adenosylmethionine,[109] while hydroxyproline is made by a post translational modification of proline.[110]

Microorganisms and plants synthesize many uncommon amino acids. For example, some microbes make 2-aminoisobutyric acid and lanthionine, which is a sulfide-bridged derivative of alanine. Both of these amino acids are found in peptidic lantibiotics such as alamethicin.[111] However, in plants, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid is a small disubstituted cyclic amino acid that is a key intermediate in the production of the plant hormone ethylene.[112]

Reactions[edit]

Amino acids undergo the reactions expected of the constituent functional groups.[113][114]

Peptide bond formation[edit]

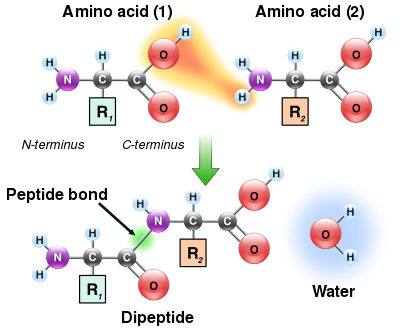

The condensation of two amino acids to form a dipeptide through a peptide bond

As both the amine and carboxylic acid groups of amino acids can react to form amide bonds, one amino acid molecule can react with another and become joined through an amide linkage. This polymerization of amino acids is what creates proteins. This condensation reaction yields the newly formed peptide bond and a molecule of water. In cells, this reaction does not occur directly; instead, the amino acid is first activated by attachment to a transfer RNA molecule through an ester bond. This aminoacyl-tRNA is produced in an ATP-dependent reaction carried out by an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase.[115] This aminoacyl-tRNA is then a substrate for the ribosome, which catalyzes the attack of the amino group of the elongating protein chain on the ester bond.[116] As a result of this mechanism, all proteins made by ribosomes are synthesized starting at their N-terminus and moving toward their C-terminus.

However, not all peptide bonds are formed in this way. In a few cases, peptides are synthesized by specific enzymes. For example, the tripeptide glutathione is an essential part of the defenses of cells against oxidative stress. This peptide is synthesized in two steps from free amino acids.[117] In the first step, gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase condenses cysteine and glutamic acid through a peptide bond formed between the side chain carboxyl of the glutamate (the gamma carbon of this side chain) and the amino group of the cysteine. This dipeptide is then condensed with glycine by glutathione synthetase to form glutathione.[118]

In chemistry, peptides are synthesized by a variety of reactions. One of the most-used in solid-phase peptide synthesis uses the aromatic oxime derivatives of amino acids as activated units. These are added in sequence onto the growing peptide chain, which is attached to a solid resin support.[119] Libraries of peptides are used in drug discovery through high-throughput screening.[120]

The combination of functional groups allow amino acids to be effective polydentate ligands for metal–amino acid chelates.[121] The multiple side chains of amino acids can also undergo chemical reactions.

Catabolism[edit]

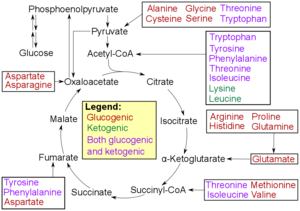

Catabolism of proteinogenic amino acids. Amino acids can be classified according to the properties of their main products as either of the following:[122]

* Glucogenic, with the products having the ability to form glucose by gluconeogenesis

* Ketogenic, with the products not having the ability to form glucose. These products may still be used for ketogenesis or lipid synthesis.

* Amino acids catabolized into both glucogenic and ketogenic products.

Amino acids must first pass out of organelles and cells into blood circulation via amino acid transporters, since the amine and carboxylic acid groups are typically ionized. Degradation of an amino acid, occurring in the liver and kidneys, often involves deamination by moving its amino group to alpha-ketoglutarate, forming glutamate. This process involves transaminases, often the same as those used in amination during synthesis. In many vertebrates, the amino group is then removed through the urea cycle and is excreted in the form of urea. However, amino acid degradation can produce uric acid or ammonia instead. For example, serine dehydratase converts serine to pyruvate and ammonia.[82] After removal of one or more amino groups, the remainder of the molecule can sometimes be used to synthesize new amino acids, or it can be used for energy by entering glycolysis or the citric acid cycle, as detailed in image at right.

Complexation[edit]

Amino acids are bidentate ligands, forming transition metal amino acid complexes.[123]

Physicochemical properties of amino acids[edit]

The ca. 20 canonical amino acids can be classified according to their properties. Important factors are charge, hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity, size, and functional groups.[35] These properties influence protein structure and protein–protein interactions. The water-soluble proteins tend to have their hydrophobic residues (Leu, Ile, Val, Phe, and Trp) buried in the middle of the protein, whereas hydrophilic side chains are exposed to the aqueous solvent. (Note that in biochemistry, a residue refers to a specific monomer within the polymeric chain of a polysaccharide, protein or nucleic acid.) The integral membrane proteins tend to have outer rings of exposed hydrophobic amino acids that anchor them into the lipid bilayer. Some peripheral membrane proteins have a patch of hydrophobic amino acids on their surface that locks onto the membrane. In similar fashion, proteins that have to bind to positively charged molecules have surfaces rich with negatively charged amino acids like glutamate and aspartate, while proteins binding to negatively charged molecules have surfaces rich with positively charged chains like lysine and arginine. There are various hydrophobicity scales of amino acid residues.[124]

Some amino acids have special properties such as cysteine, that can form covalent disulfide bonds to other cysteine residues, proline that forms a cycle to the polypeptide backbone, and glycine that is more flexible than other amino acids.

Many proteins undergo a range of posttranslational modifications, whereby additional chemical groups are attached to the amino acid side chains. Some modifications can produce hydrophobic lipoproteins,[125] or hydrophilic glycoproteins.[126] These type of modification allow the reversible targeting of a protein to a membrane. For example, the addition and removal of the fatty acid palmitic acid to cysteine residues in some signaling proteins causes the proteins to attach and then detach from cell membranes.[127]

Table of standard amino acid abbreviations and properties[edit]

| Amino acid | Letter code | Side chain | Hydropathy index[128] |

Molar absorptivity[129] | Molecular mass | Abundance in proteins (%)[130] | Standard genetic coding, IUPAC notation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1 | Class | Polarity[131] | Charge, at pH 7.4[131] | Wavelength, λmax (nm) | Coefficient, ε (mM−1·cm−1) | |||||

| Alanine | Ala | A | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | 1.8 | 89.094 | 8.76 | GCN | ||

| Arginine | Arg | R | Basic | Basic polar | Positive | −4.5 | 174.203 | 5.78 | MGR, CGY (coding codons can also be expressed by: CGN, AGR) | ||

| Asparagine | Asn | N | Amide | Polar | Neutral | −3.5 | 132.119 | 3.93 | AAY | ||

| Aspartic acid | Asp | D | Acid | Acidic polar | Negative | −3.5 | 133.104 | 5.49 | GAY | ||

| Cysteine | Cys | C | Sulfuric | Nonpolar | Neutral | 2.5 | 250 | 0.3 | 121.154 | 1.38 | UGY |

| Glutamine | Gln | Q | Amide | Polar | Neutral | −3.5 | 146.146 | 3.9 | CAR | ||

| Glutamic acid | Glu | E | Acid | Acidic polar | Negative | −3.5 | 147.131 | 6.32 | GAR | ||

| Glycine | Gly | G | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | −0.4 | 75.067 | 7.03 | GGN | ||

| Histidine | His | H | Basic aromatic | Basic polar | Positive, 10% Neutral, 90% |

−3.2 | 211 | 5.9 | 155.156 | 2.26 | CAY |

| Isoleucine | Ile | I | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | 4.5 | 131.175 | 5.49 | AUH | ||

| Leucine | Leu | L | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | 3.8 | 131.175 | 9.68 | YUR, CUY (coding codons can also be expressed by: CUN, UUR) | ||

| Lysine | Lys | K | Basic | Basic polar | Positive | −3.9 | 146.189 | 5.19 | AAR | ||

| Methionine | Met | M | Sulfuric | Nonpolar | Neutral | 1.9 | 149.208 | 2.32 | AUG | ||

| Phenylalanine | Phe | F | Aromatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | 2.8 | 257, 206, 188 | 0.2, 9.3, 60.0 | 165.192 | 3.87 | UUY |

| Proline | Pro | P | Cyclic | Nonpolar | Neutral | −1.6 | 115.132 | 5.02 | CCN | ||

| Serine | Ser | S | Hydroxylic | Polar | Neutral | −0.8 | 105.093 | 7.14 | UCN, AGY | ||

| Threonine | Thr | T | Hydroxylic | Polar | Neutral | −0.7 | 119.119 | 5.53 | ACN | ||

| Tryptophan | Trp | W | Aromatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | −0.9 | 280, 219 | 5.6, 47.0 | 204.228 | 1.25 | UGG |

| Tyrosine | Tyr | Y | Aromatic | Polar | Neutral | −1.3 | 274, 222, 193 | 1.4, 8.0, 48.0 | 181.191 | 2.91 | UAY |

| Valine | Val | V | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | 4.2 | 117.148 | 6.73 | GUN | ||

Two additional amino acids are in some species coded for by codons that are usually interpreted as stop codons:

| 21st and 22nd amino acids | 3-letter | 1-letter | Molecular mass |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selenocysteine | Sec | U | 168.064 |

| Pyrrolysine | Pyl | O | 255.313 |

In addition to the specific amino acid codes, placeholders are used in cases where chemical or crystallographic analysis of a peptide or protein cannot conclusively determine the identity of a residue. They are also used to summarise conserved protein sequence motifs. The use of single letters to indicate sets of similar residues is similar to the use of abbreviation codes for degenerate bases.[132][133]

| Ambiguous amino acids | 3-letter | 1-letter | Amino acids included | Codons included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any / unknown | Xaa | X | All | NNN |

| Asparagine or aspartic acid | Asx | B | D, N | RAY |

| Glutamine or glutamic acid | Glx | Z | E, Q | SAR |

| Leucine or isoleucine | Xle | J | I, L | YTR, ATH, CTY (coding codons can also be expressed by: CTN, ATH, TTR; MTY, YTR, ATA; MTY, HTA, YTG) |

| Hydrophobic | Φ | V, I, L, F, W, Y, M | NTN, TAY, TGG | |

| Aromatic | Ω | F, W, Y, H | YWY, TTY, TGG (coding codons can also be expressed by: TWY, CAY, TGG) | |

| Aliphatic (non-aromatic) | Ψ | V, I, L, M | VTN, TTR (coding codons can also be expressed by: NTR, VTY) | |

| Small | π | P, G, A, S | BCN, RGY, GGR | |

| Hydrophilic | ζ | S, T, H, N, Q, E, D, K, R | VAN, WCN, CGN, AGY (coding codons can also be expressed by: VAN, WCN, MGY, CGP) | |

| Positively-charged | + | K, R, H | ARR, CRY, CGR | |

| Negatively-charged | − | D, E | GAN |

Unk is sometimes used instead of Xaa, but is less standard.

In addition, many nonstandard amino acids have a specific code. For example, several peptide drugs, such as Bortezomib and MG132, are artificially synthesized and retain their protecting groups, which have specific codes. Bortezomib is Pyz–Phe–boroLeu, and MG132 is Z–Leu–Leu–Leu–al. To aid in the analysis of protein structure, photo-reactive amino acid analogs are available. These include photoleucine (pLeu) and photomethionine (pMet).[134]

Chemical analysis[edit]

The total nitrogen content of organic matter is mainly formed by the amino groups in proteins. The Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN) is a measure of nitrogen widely used in the analysis of (waste) water, soil, food, feed and organic matter in general. As the name suggests, the Kjeldahl method is applied. More sensitive methods are available.[135][136]