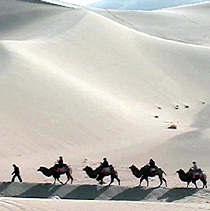

Kumtag Desert

Jump to navigationJump to search

The Kumtag Desert (Chinese: 库姆塔格沙漠; pinyin: Kùmǔtǎgé Shāmò, “kum-tag” meaning “sand-mountain” in a number of Turkic languages), is an arid landform in Northwestern China, which was proclaimed as a national park in the year 2002.

Definitions[edit]

Broad[edit]

The oval Tarim Basin with its central Taklamakan Desert is bounded on the north, west, and south by mountains. On the east side the Kumtag is an unbroken plain about 100 miles from north to south that runs from the Taklamakan to Gansu province and Mongolia. Many modern maps do not show a Kumtag in this sense, which implies that the usage may be out of date.

The Kumtag Desert is a section of the Taklamakan Desert that lies east-southeast of the Desert of Lop. It is bordered by Dunhuang in the east, Tian Shan in the north and has an area of more than 22,800 square kilometers. Its southern rim is marked by a labyrinth of hills, dotted in groups and irregular clusters. Between these and the Altyn-Tagh is a broad latitudinal valley, seamed with watercourses that come down from the foothills of the Altyn-tagh. Grapes and other crops are grown in oases in low-lying areas. Elsewhere, the desert supports scrubby desert plants, water reaching them in some instances at intervals of years only. This part of the desert has a general slope northwest towards the relative depression of the Kara-koshun. A noticeable feature of the Kumtag is the presence of large accumulations of drift-sand, especially along the foot of the desert ranges, where it rises into dunes sometimes as much as 250 feet (76 m) in height and climbs the flanks of ranges themselves.[1]

Administratively, the desert is located in the Ruoqiang (Qakilik) County of Xinjiang and Aksai Kazakh Autonomous County and Dunhuang City of Gansu, near their border with Qinghai.

Narrow[edit]

A satellite image of the Kumtag. The ear-shaped formation on the left is the Lop Nor; the mountain range along the bottom edge of the photo is the Altyn Tagh

A map published by the National Geographic Society[2] shows a much smaller Kumtag. This is a rectangle with a northwest corner south of Lop Nor, a southern edge along the Altyn-Tagh and an eastern edge just beyond the Gansu border. Near the northeast corner is the Jade Gate which is often taken as the western end of the Great Wall. From space it appears as a belt of orange sand dunes. This is probably the 2500 square kilometer area mentioned below.

Ongoing desertification[edit]

The Kumtag Desert is expanding and threatening to engulf previously productive lands with its arid wasteland character.[3] Several years prior the estimated size of the desert was 2500 square kilometres, but with recent expansion, the Kumtag Desert is already considerably larger as of 2008.

The Kumtag Desert is continuing a process of expansion that is the result of centuries of overgrazing of this region that is beyond its carrying capacity. According to the AFP news report of November, 2007: “Towering sand dunes [of the Kumtag Desert] loom over the ancient Chinese city of Dunhuang“.[3] According to Hogan: “Rapid expansion of the Kumtag Desert and other dunes formations threaten to engulf Yungang and other archaeological sites”; moreover, the desertification adjacent to the Kumtag Desert is part of a larger problem in northern China where the present rate of desertification in this single region of China (e.g. Northern China) now exceeds 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2) per annum.[4] To mitigate the desertification, the town of Dunhuang has placed severe limitations on immigration, and has also placed restrictions on new water-well development or new farm additions.[3]

Prevailing winds and sands[edit]

The prevailing winds in this region would appear to blow from the west and northwest during the summer, winter and autumn. Though in spring, when they certainly are more violent, they no doubt come from the northeast, as in the desert of Lop. The arrangement of the sand here agrees perfectly with the law laid down by Grigory Potanin, that in the basins of Central Asia the sand is heaped up in greater mass on the south, all along the bordering mountain ranges where the floor of the depressions lies at the highest level. The country to the north of the desert ranges is thus summarily described by Sven Hedin: “The first zone of drift sand is succeeded by a region that exhibits proofs of wind modelling on an extraordinarily energetic and well-developed scale, the results corresponding to the jardangs and the wind-eroded gullies of the Desert of Lop. Both sets of phenomena lie parallel to one another; from this we may infer that the winds which prevail in the two deserts are the same. Next comes, sharply demarcated from the zone just described, a more or less thin kamish steppe growing on level ground; and this in turn is followed by another very narrow belt of sand, immediately south of Achik-kuduk Finally in the extreme north we have the characteristic and sharply defined belt of kamish steppe, stretching from east-northeast to west-southwest and bounded on north and south by high, sharp cut clay terraces.

“At the points where we measured them the northern terrace was 113 feet (34 m) high and the southern 853/4 feet….Both terraces belong to the same level, and would appear to correspond to the shore lines of a big bay of the last surviving remnant of the Central Asian Mediterranean. At the point where I crossed it the depression was 6 to 7 miles (11 km), wide, and thus resembled a flat valley or immense river-bed.”[1][5]

The moving sands of the Kumtag are of a concern for the designers of the Golmud–Dunhuang Railway, which will cross the eastern edge of this desert in the Shashangou area, between Dunhuang and the Altyn-Tagh–Qilian mountain system. There was a concern that the “megadunes” characteristic of this area may shift, burying the railway. However, geological research indicated that the “megadunes” are mostly formed by solid subsoil, rather than just sand. Although there is still the issue of drifting sand, it is thought by the experts that the sand is mostly blown along the direction of the future railway rather than across it, and can be handled with certain precautions.[6]