Odrysian kingdom

Jump to navigationJump to search

|

Odrysian Kingdom

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 480 BC[1]–46 AD | |||||||||

Odrysian kingdom under Sitalces

|

|||||||||

| Common languages | Thracian language | ||||||||

| Religion | Thracian polytheism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||

|

• Teres

|

480 BC[1] | ||||||||

| 46 AD | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Odrysian Kingdom (/oʊˈdrɪʒən/; Ancient Greek: Βασίλειον Ὀδρυσῶν; Latin: Regnum Odrysium) was a state union of over 40 Thracian tribes[2] and 22 kingdoms[3] that existed between the 5th century BC and the 1st century AD. It consisted mainly of present-day Bulgaria, spreading to parts of Southeastern Romania (Northern Dobruja), parts of Northern Greece and parts of modern-day European Turkey.

It is suggested that the kingdom had no capital. Instead, the kings may have moved between residences.[4] The main royal residence was the city of Odryssa (assumed to be either modern Plovdiv,[5] as inscribed on coins; or Uscudama, modern Edirne.[2]) Another royal residence believed to have been constructed by Cotys I (383–358 BC) is in the village of Starosel, while in 315 BC Seuthopolis was built as a capital.[2] A later residence may have been the city of Vize.[6] The kingdom broke up and Kabyle was a co-capital by the end of the 4th century BC.[7]

The Odrysians[edit]

The Odrysians (Odrysae or Odrusai, Ancient Greek: Ὀδρύσαι) were one of the most powerful Thracian tribes that dwelled in the plain of the Hebrus river.[8] This would place the tribe in the modern border area between Southeastern Bulgaria, Northeastern Greece and European Turkey, centered around the city of Plovdiv[9] or Edirne.[10][11] The river Artescus[12] passed through their land as well. Xenophon[13] writes that the Odrysians held horse races and drank large amounts of wine after the burial of their dead warriors. Thucydides writes on their custom, practised by most Thracians, of giving gifts for getting things done,[14] which was refuted by Heraclides. Herodotus was the first writer to mention the Odrysae.

History[edit]

Thrace had been part of the Persian empire from 516 BC[15] during the rule of Darius the Great, and was re-subjugated by Mardonius in 492 BC.[16] During Persian rule, it was made part of the Skudra satrapy (province). Parts were occupied by Scythians and by Greek colonists.

The Odrysian state was the first Thracian kingdom that acquired power in the region, through the unification[17] of many Thracian tribes under a single ruler, King Teres,[18] probably achieved by the 460s BC after the Persian defeat in Greece.[19]

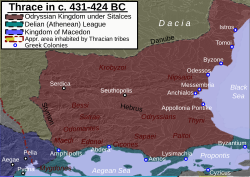

Initially, during the reign of Teres or[20] Sitalces the state was at its zenith and extended from the Black Sea to the east, the Danube to the north, the region populated by the tribe called Triballi to the north-west, and the basin of the river Strymon to the south-west and towards the Aegean. This was equivalent to present-day Bulgaria, Romanian Dobruja, Turkish East Thrace and Greek Western Thrace between the Hebrus and the Strymon, except the Aegean and Black seas coasts which were mostly occupied by Greek cities.[21] Sovereignty was never exercised over all of these lands as it varied based on tribal politics.

Historian Z.H. Archibald writes:

The Odrysians created the first state entity which superseded the tribal system in the east Balkan peninsula. Their kings were usually known to the outside world as kings of Thrace, although their power did not extend by any means to all Thracian tribes. Even within the confines of their kingdom the nature of royal power remained fluid, its definition subject to the dictates of geography, social relationships, and circumstance

This large territory was populated with a number of Thracian and Daco–Moesian tribes that united under the reign of a common ruler, and began to implement common internal and external policies. These were favourable conditions for overcoming the tribal divisions, which could have led gradually to the formation of a more stable ethnic community. This was not realised and the period of power of the Odrysian kingdom was brief. Despite the attempts of the Odrysian kings to bolster their central power, the separatist tendencies were very strong. Odrysian military strength was based on intra-tribal elites[22] making the kingdom prone to fragmentation. Some tribes were constantly trying to separate, while others remained outside the borders of the kingdom. At the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 4th century BC, as a result of conflicts, the Odrysian kingdom split into three parts.[23] The political and military decline continued, while Macedonia was rising as a dangerous and ambitious neighbour.[24]

According to the Greek historians Herodotus and Thucydides, a royal dynasty emerged from among the Odrysian tribe in Thrace around the end of the 5th century BC, which came to dominate much of the area and peoples between the Danube and the Aegean for the next century. Later writers, royal coin issues, and inscriptions indicate the survival of this dynasty into the early 1st century AD, although its overt political influence declined progressively first under Persian, Macedonian and Roman encroachment. Despite their demise, the period of Odrysian rule was of decisive importance for the future character of south-eastern Europe under the Roman Empire and beyond.

Teres’ son, Sitalces, proved to be a good military leader, forcing the tribes that defected from the alliance to acknowledge his sovereignty. The rich state that spread from the Danube to the Aegean built roads to develop trade and built a powerful army. In 429 BC, Sitalces allied himself with the Athenians[25] and organized a massive campaign against the Macedonians, with a vast army from independent Thracian and Paeonian tribes. According to Thucydides, it included as many as 150,000 men, but was obliged to retire through the failure of provisions, and the coming winter.[26] Greek as a lingua franca had been spoken at least by some members of the royal household in the fifth century BC and became the language of administrators; the Greek alphabet was adopted as the new Thracian script.[27]

After the kingdom had split itself in three semi-independent kingdoms, Philip II of Macedon invaded and conquered much of Thrace. Some Odrysian kings and other Thracian tribes submitted to the Macedonians and paid taxes at different times to Philip II, Alexander the Great and Philip V. Two of the three kingdoms were forced into vassal status by Philip II in 352 BC, while in 342–341 BC he conquered the Odrysian heartland deposing reigning kings or rebellious vassals. Nevertheless, Seuthes III (341-300 BC) was able to survive despite the expansion of Macedonian power under Philip, maintaining continuity of the kingdom.

However, by 323 BC it was probably only as a client state on a power-sharing basis with the appointed Macedonian satrap of Thrace Lysimachus. Seuthes battled frequently with Lysimachus. Seuthes established his capital at Seuthopolis from 320 BC until it was sacked by the Celts in 281 BC.

By 212 BC an army led by an Odrysian king Pleuratus destroyed the Celtic kingdom and its capital Tylis. The Odrysian kingdom had maintained continuity with its own kings, but had broken up into several kingdoms (including Canite and Odrissae) by the early second century BC. The kingdoms succumbed to complete Roman conquest by 146 BC.

In 100 BC a Thracian kingdom was restored, possibly by a son of Beithys, one of the last kings of the Odrissae. However, it is not clear if it was a vassal of Rome or entirely independent. Several years later, some Thracians and Celts overran the southern Balkans, Epirus, Dalmatia and northern Greece, and penetrated the Peloponnese.

A kingdom of another Odrysian bloodline had re-emerged in 55 BC (Sapei) and by 30 BC it conquered or otherwise controlled the other Odrysian kingdom (Antaea), although it, along with[clarification needed] other Thracian tribes, became a Roman proxy soon afterward. By 11 BC, the uncle of the Roman emperor Augustus was the Odrysian king, which led to the gradual Romanization of the region. The Odrysian king Rhoemetalces III was murdered by his co-ruler and wife Pythodoris II, and his kingdom was completely subjected to Roman rule in 46 AD.[2][28][29][30]

Culture[edit]

Odrysian crafts and metalworking were largely a product of Persian influence.[31][32] Thracians as Dacians and Illyrians all decorated themselves with status-enhancing tattoos.[33] Thracian warfare was affected also by Celts and the Triballi had adopted Celtic equipment. Thracian clothing is regarded for its quality and texture and was made up of hemp, flax or wool. Their clothing resembled that of the Scythians including jackets with coloured edges, pointed shoes and the Getai tribe were so similar to the Scythians that they were often confused with them. The nobility and some soldiers wore caps. There was a mutual influence between the Greeks and the Thracians.[34] Greek customs and fashions contributed to the recasting of east Balkan society. Among the nobility Greek fashions in dress, ornament and military equipment were popular.[35] Unlike the Greeks, the Thracians often wore trousers. Thracian kings were influenced by Hellenization.[36]

Archaeology[edit]

Residences and temples of the Odrysian kingdom have been found, particularly around Starosel in the Sredna Gora mountains.[37] Archaeologists have uncovered the northeastern wall of the Thracian kings’ residence, 13 m in length and preserved up to 2 m in height.[38] They also found the names of Cleobulus and Anaxandros, Philip II of Macedon’s generals who led the assault on the Odrysian kingdom.[38]

List of Odrysian kings[edit]

|

Part of a series on the

|

|---|

| History of Bulgaria |

|

|

| Main category |

The list below includes the known Odrysian kings of Thrace, but much of it is conjectural. Various other Thracian kings (some of them perhaps Odrysian like Pleuratus) are included as well.[1] Odrysian kings, though called Kings of Thrace, never exercised sovereignty over all of Thrace.[39] Control varied according to tribal relationships.[40] Odrysian kings (names are presented in Greek or Latin forms):

- Teres I, son of Odryses, (480[1]/450–430 BC[2])

- Sparatocos, brother or son of Teres I (450 / 431–430 BC)

- Sitalces, son of Teres I (431–424 BC)

- Sadocos, son of Sitalces (425–424 BC)

- Seuthes I, nephew/son of Sparatocos (424–396 BC)

- Metokos/Amatokos I, son of Sitalces

- Amadocus I, son of Teres I or Metokos (410–390 BC)[41]

- Seuthes II, son of Maisades, Sparatokos, or grandson of Teres I, king in southern districts (405–391 BC)

- Hebryzelmis, son of Seuthes I or brother (390–384 BC)

- Maisades, father of Seuthes II (390–384 BC)

- Cotys I, son of Seuthes II (384–359 BC)

- Cersobleptes, son of Cotys I, king in eastern Thrace (359-341 BC)

- Berisades, probable brother of Cersobleptes or a grandson of Seuthes I, king in western Thrace in Strimos (359–352 BC)

- Amatokos II, brother of Cersobleptes, king in central Thrace in Chersonese & Maroneia (359–351 BC)

- Cetriporis, son of Berisades, king in western Thrace in Strimos (358–347 BC)

- Skostodokos, son of Berisades, king in western Thrace in Strimos (c. 351 BC)

- Teres II, son of Amatokos II, king in central Thrace in Chersonese & Maroneia (351–342 BC)

- Seuthes III, son of Cotys I (341–300 BC)

- Cotys II, son of Seuthes III (300–280 BC)

- Raizdos/Roigos, son of Cotys II (c. 280 BC)

- Odoroes, alternative co-ruler (c. 280–273 BC)

- Adaeus, alternative co-ruler (c. 280–273 BC)

- Scostodos, son of Berisades, alternative co-ruler (c. 275 BC)

- Orsoaltios, alternative co-ruler (c. 265 BC)

- Kersivaulos, alternative co-ruler (c. 260 BC)

- Cotys III, son of Raizdos (c. 260 BC)

- Teres III, (c. 250 BC)

- Rhescuporis I, son of Cotys III (240–215 BC)

- Adaios, alternative co-ruler (c. 235 BC)

- Seuthes IV, son of Rhescuporis I or of Teres III (213/215 – 190/175 BC)

- Pleuratus,[42] alternative co-ruler (213–208 BC)

- Ciroadas (c. 212-205 BC)

- Amatokos III (until 184 BC)

- Abrupolis, Sapei king (200–172 BC)

- Teres IV, son of Amatokos III, or of Seuthes III (183–172 BC)

- Teres V (172–148 BC)

- Cotys IV, son of Seuthes IV (180/170 – 168/160 BC)

- Diagil / Diygyles / Diygyles / Diegylos / Dyegilos / Diagylis / Tsizelmi (168/150 – 140 BC or 180 BC)

- Biz / Byzas / Byses / Beithys / Tsizelmi (168/166 BC or 148/146 BC or 180 BC)

- Sothimes (c. 163 BC)

- Teres VI (c. 149 BC)

- Amatokos IV, rebel (80–90 BC)

Restored Astaean and Sapaean kingdom[edit]

- Cotys V, son of Beithys (100–87 BC)

- Sadalas I, son of Cotys V (87–79 BC)

- Cotys VI, son of Sadalas I (79–45 BC)

- Cotys I, son of Rhoemetalces (55–48 BC)[29]

- Rhescuporis I, son Cotys I (48–42 BC)

- Cotys ?, son of Rhescuporis (42–31 BC)

- Sadalas II, son of Cotys VI (44–42 BC)

- Raskos, co-ruler (c. 42 BC)

- Sadalas III, son of Sadalas II (c. 31 BC)

- Cotys VII, son of Sadalas II (31–18 BC)

- Rhescuporis II, son of Cotys VII, north-west Sapaei king (19/18–12/11 BC)

- Cotys VIII (c. 11 BC)

- Rhoemetalces I, uncle of Rhescuporis and son of Cotys (31/11 BC – AD 12)

- Cotys ? , son of Rhoemetalces, south-east Sapaei king (12–19 AD)

- Rhoemetalces II, son of Raskouporis II (19–38 AD)

- Rhoemetalces III, son of Cotys (38–46 AD)

- Pythodoris II, co-ruling wife and cousin (38–46 AD)

Odrysian treasures[edit]

-

Sinemorets Gold figurines

-

Vazovo Thracian Pegasus

-

Golden mask probably of Teres I, the first ruler of the Odrysian kingdom

-

Bronze Head probably of Seuthes III found in Golyamata Kosmatka

-

King Cotys I‘s Borovo Treasure