Troy

Jump to navigationJump to search

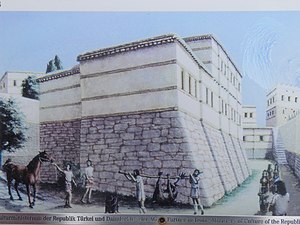

East tower and cul-de-sac wall before the east gate of Troy VI, considered the floruit of Bronze Age Troy. The complex would have been surmounted and augmented by mudbrick structures.

|

|

| Alternative name | Truwisa |

|---|---|

| Location | Tevfikiye, Çanakkale Province, Turkey |

| Region | Troad |

| Coordinates | 39°57′27″N 26°14′20″ECoordinates: 39°57′27″N 26°14′20″E |

| Type | Walled city |

| Part of | Historical National Park of Troia |

| Area | Varies depending on time period. 13th century BC (Troy VI): 300,000 square metres (74 acres)[1] |

| Height | The unexcavated hill of Hisarlik was 31.2 metres (102 ft) high, 38.5 metres (126 ft) elevation. The city began as a citadel at the top, ended by covering the entire height to the south (the north being precipitous)[2] |

| History | |

| Builder | Various peoples living in the region at different historical periods |

| Material | Native limestone, wood, mudbrick |

| Founded | 3500 BC from the start of Troy Zero |

| Abandoned | Main periods of abandonment as a residential city: 950 BC – 750 BC 450 AD – 1200 AD 1300 AD |

| Cultures | Bronze Age (entire) Dark Age (partial) Classical and Hellenistic Periods (entire) Roman Empire (entire) Byzantine Empire (one century) |

| Associated with | Luwian speakers in the Late Bronze Age, Greek speakers subsequently |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | The Calverts, Heinrich Schliemann, Wilhelm Dörpfeld Carl Blegen and the University of Cincinnati, Manfred Korfmann and the University of Tübingen, Rüstem Aslan of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University (current) |

| Condition | High authenticity, low degree of reconstruction |

| Ownership | State property of the Turkish Republic through the Ministry of Culture and Tourism |

| Management | General Directorate of Cultural Heritage and Museums in conjunction with other relevant local organizations |

| Public access | Regular visiting hours, bus access, some parking |

| Website | Unesco WHS 849 |

| Official name | Archaeological Site of Troy |

| Designated | 1998 (22nd session) |

The Troy ridge, 1880, sketched from the plain below. This woodcut is published in some of the works of Schliemann. He describes the view as being “from the north,” necessarily meaning from the northwest. Only the west end of the ridge is visible. The angular appearance is due to Schliemann.s excavations. The notch at the top is “Schliemann’s Trench.” For much of Troy’s archaeological history, the plain was an inlet of the sea, with Troy Ridge projecting into it, hence Korfmann’s classification of it as a maritime city.

Troy (Ancient Greek: Τροία, Troía, Ἴλιον, Ílion or Ἴλιος, Ílios; Latin: Troia and Ilium;[note 1] Hittite: 𒌷𒃾𒇻𒊭 Wilusa or 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 Truwisa;[3][4] Turkish: Truva or Troya) was a city in the northwest of Asia Minor (modern Turkey), southwest of the Çanakkale Strait, south of the mouth of the Dardanelles and northwest of Mount Ida.[note 2] The location in the present day is the hill of Hisarlik and its immediate vicinity. In modern scholarly nomenclature, the Ridge of Troy (including Hisarlik) borders the Plain of Troy, flat agricultural land, which conducts the lower Scamander River to the strait. Troy was the setting of the Trojan War described in the Greek Epic Cycle, in particular in the Iliad, one of the two epic poems attributed to Homer. Metrical evidence from the Iliad and the Odyssey suggests that the name Ἴλιον (Ilion) formerly began with a digamma: Ϝίλιον (Wilion);[note 3] this is also supported by the Hittite name for what is thought to be the same city, Wilusa. According to archaeologist Manfred Korfmann, Troy’s location near the Aegean Sea, as well as the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, made it a hub for military activities and trade, and the chief site of a culture that Korfmann calls the “Maritime Troja Culture”, which extended over the region between these seas.[5]

The city was destroyed at the end of the Bronze Age – a phase that is generally believed to represent the end of the Trojan War – and was abandoned or near-abandoned during the subsequent Dark Age. After this, the site acquired a new, Greek-speaking population, and the city became, along with the rest of Anatolia, a part of the Persian Empire. The Troad was then conquered by Alexander the Great, an admirer of Achilles, who he believed had the same type of glorious (but short-lived) destiny. After the Roman conquest of this now Hellenistic Greek-speaking world, a new capital called Ilium (from Greek: Ἴλιον, Ilion) was founded on the site in the reign of the Roman Emperor Augustus. It flourished until the establishment of Constantinople, became a bishopric, was abandoned, repopulated for a few centuries in the Byzantine era, before being abandoned again (although it has remained a titular see of the Catholic Church).

Troy’s physical location, on Hisarlik, was forgotten in antiquity and, by the early modern era, even its existence as a Bronze Age city was questioned and held to be mythical or quasi-mythical. The Scottish journalist Charles Maclaren, in 1822, was the first modern scholar to categorically identify Hisarlik as the likely location of Troy.[6][7] During the mid-19th century the Calvert family, wealthy Levantine English settlers of the Troad, occupying a working farm a few miles from Hisarlik, purchased much of the hill in the belief that it contained the ruins of Troy. They were antiquarians. Two of the family, Frederick and especially the youngest, Frank, surveyed the Troad and conducted a number of trial excavations there. In 1865, Frank Calvert excavated trial trenches on the hill, discovering the Roman settlement. Realizing he did not have the funds for a full excavation, he attempted to recruit the British Museum, and was refused. A chance meeting with Calvert in Çanakkale and a visit to the site by Heinrich Schliemann, a wealthy German businessman and archaeologist, also looking for Troy, offered a second opportunity for funding.[8] Schliemann had been at first skeptical about the identification of Hisarlik with Troy, but was persuaded by Calvert.[9] As Schliemann was about to leave the area, Calvert wrote to him asking him to take over the entire excavation. Schliemann agreed. The Calverts, who made their money in the diplomatic service, expedited the acquisition of a Turkish firman. In 1868, Schliemann excavated an initial deep trench across the mound called today “Schliemann’s trench.” These excavations revealed several cities built in succession. Subsequent excavations by following archaeologists elaborated on the number and dates of the cities.

Since the rediscovery of Troy, a village near the ruins named Tevfikiye has supported the archaeological site and the associated tourist trade. It is in the modern Çanakkale Province, 30 kilometres (19 mi) south-west of the city of Çanakkale. On modern maps, Ilium is shown a short distance inland from the Scamander estuary, across the Plain of Troy.

Troy was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1998.

Homeric Troy[edit]

Polyxena Sarcophagus in Troy Museum, named after the depiction of the sacrifice of Polyxena, the last act of the Greeks at Troy.

Homeric Troy refers primarily to the city described in the Iliad, one of the earliest literary works in Europe. This is a long originally oral poem in its own dialect of ancient Greek in dactylic hexameter, in tradition composed by a blind poet of the Anatolian Greek coast, Homer. It covers the 10th year of a war against Troy conducted by a coalition of Achaean, or Greek, states under the leadership of a high king, Agamemnon of Mycenae. The city was defended by a coalition of states in the Dardanelles and West Anatolian region under another high king, Priam, whose capital was Troy. The cause of the war was the elopement of Agamemnon’s brother’s wife, Helen, with Paris, a prince of Troy.

After the literary time of the poem, the city was destroyed when the Greeks pretended to leave after secreting a squad of soldiers in a gigantic wooden horse monument, which the Trojans brought inside the walls.[note 4] In the dead of night they exited the horse and opened the gates to the Achaeans nearby. Troy was burned and the population slaughtered, although many had other fates.

Besides the Iliad, there are references to Troy in the other major work attributed to Homer, the Odyssey, as well as in other ancient Greek literature (such as Aeschylus‘s Oresteia). The Homeric legend of Troy was elaborated by the Roman poet Virgil in his Aeneid. The fall of Troy with the story of the Trojan Horse and the sacrifice of Polyxena, Priam’s youngest daughter, is the subject of a later Greek epic by Quintus Smyrnaeus (“Quintus of Smyrna”).

The Greeks and Romans took for a fact the historicity of the Trojan War and the identity of Homeric Troy with a site in Anatolia on a peninsula called the Troad (Biga Peninsula). Alexander the Great, for example, visited the site in 334 BC and there made sacrifices at tombs associated with the Homeric heroes Achilles and Patroclus. In Piri Reis book Kitab-ı Bahriye (Book of the Sea, 1521) which details many ports and islands of the Mediterranean, the description of the island called Tenedos mentions Troy and its ruins, lying on the shore opposite of the island.[10]

The fact that the topography around the site matches the topographic detail of the poem gives to the poem a lifelike quality not equaled by other epics. In the Iliad, the Achaeans set up their camp near the mouth of the River Scamander (modern Karamenderes),[11] where they beached their ships. The city of Troy itself stood on a hill, across the plain of Scamander, where the battles of the Trojan War took place. The site of the ancient city is some 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) from the coast today, but 3,000 years ago the mouths of Scamander were much closer to the city,[12] discharging into a large bay that formed a natural harbor, which has since been filled with alluvial material. Recent geological findings have permitted the identification of the ancient Trojan coastline, and the results largely confirm the accuracy of the Homeric geography of Troy.[13]

In November 2001, the geologist John C. Kraft from the University of Delaware and the classicist John V. Luce from Trinity College, Dublin, presented the results of investigations, begun in 1977, into the geology of the region.[14] They compared the present geology with the landscapes and coastal features described in the Iliad and other classical sources, notably Strabo‘s Geographia, and concluded that there is a regular consistency between the location of Schliemann’s Troy and other locations such as the Greek camp, the geological evidence, descriptions of the topography and accounts of the battle in the Iliad.[15]

The Dark Age following the fall of Troy is called so because for a time writing in Greece disappeared. There are consequently no historians from the period. Writing reappeared in the Archaic Period, after which, in the Classical Period, many historians turned their pens to record such histories of the Trojan War as had survived in oral tradition. They offer a span of about two centuries from the 1334 BC date of Duris of Samos to the 1135 BC date of Ephoros of Kyme in Aeolis. Blegen preferred the 1184 BC date of Eratosthenes, which was in his day the most favored.[16][note 5] Whether or not the archaeology matched this span and these dates was to be determined by excavation.

Search for Troy[edit]

With the rise of critical history, Troy and the Trojan War were consigned to legend.[note 6] However, not everyone agreed with this view. The dissidents were to become the first archaeologists at Troy. The true location of ancient Troy had for centuries remained the subject of interest and speculation.[17] Travellers in Anatolia looked for possible locations. Because of its name, the Troad peninsula was highly suspect.

Early modern travellers in the 16th and 17th centuries, including Pierre Belon and Pietro Della Valle, had identified Troy with Alexandria Troas, a ruined town approximately 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of the currently accepted location.[18] In the late 18th century, Jean Baptiste LeChevalier identified a location near the village of Pınarbaşı, Ezine, a mound approximately 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) south of the currently accepted location. Published in his Voyage de la Troade, it was the most commonly accepted theory for almost a century.[19]

In 1822, the Scottish journalist Charles Maclaren was the first to identify with confidence the position of the city as it is now known.[20][7] In the second half of the 19th century archaeological excavation of the site believed to have been Homeric Troy began. As the Iliad is taught in every Greek language curriculum in the world, interest in the site has been unflagging. Homeric experts often memorize large parts of the poem. Literary quotes are commonplace. Since the Calvert family began excavation at Hisarlik, hundreds of interested persons have excavated there. Fortunately all excavation has been conducted under the management of key persons termed its “archaeologists.” Their courses of excavation have been divided into the phases described below. Sometimes there have been decades between phases. Today interest in the site is as strong as ever. Further plans for excavation have no end in the foreseeable future.

The Calverts[edit]

Frank Calvert, 1866, age 38. Picture was excised from a family group photograph displaying 12 persons in front of the farmhouse near Hisarlik[21]

Frank Calvert was born into an English Levantine family on Malta in 1828. He was the youngest of six sons and one daughter born to James Calvert and his wife, the former Louisa Lander, the sister of Charles Alexander Lander, James’ business partner. In social standing they were of the aristocracy. James was a distant relative of the Calverts who founded Baltimore, Maryland,[22] and Louisa was a direct descendant of the Campbells of Argyll (Scottish clansmen).[23] Not having inherited any wealth, they took to the colonies, married in Ottoman Smyrna in 1815, and settled in Malta, which had changed hands from the French to the British Empire with the Treaty of Paris (1814). They associated with the “privileged” social circles of Malta, but they were poor. James clerked in the mail and grain offices of the Civil Service.[24]

The family regarded itself as a single enterprise. They shared property, assisted each other, lived together and had common interests, one of which was the antiquities of the Troad. They did not do well in Malta, but in 1829 the Dardanelles region underwent an upswing of its business cycle due to historical circumstances. The Greek War of Independence was about to be concluded in favor of an independent state by the Treaty of Constantinople (1832). The Levant Company, which had had a monopoly on trade through the Dardanelles, was terminated. The price in pounds of the Turkish piastre fell. A manyfold increase in British traffic through straits was anticipated. A new type of job suddenly appeared: British Consul in the Dardanelles, which brought wealth with it.[25][note 7]

Charles Lander[edit]

Charles Lander applied, and was made British Consul of the Dardanelles in 1829. He spoke five languages, knew the region well, and had the best connections. A row of new consular offices was being constructed in Çanakkale along the shore of the strait. He was at first poor. In 1833 he bought a house in town ample enough to invite his sister’s sons to join him in the enterprise. Without exception they left home at 16 to be tutored in the trade at their uncle’s house and placed in lucrative consular positions. Frederick, the eldest, stayed on to assist Charles. The youngest, Frank, at school in Athens, arrived last, but his interest in archaeology led him into a different career.[22]

Çanakkale was a boom town. In 1831 Lander married Adele, a brief but idyllic relationship that gave them three daughters in quick succession. When the Calverts began to arrive, finding quarters in the crowded town proved to be difficult. The Turkish building code requiring buildings of wood, conflagrations were frequent.[26] The family escaped one fire with nothing but the clothes they were wearing.[27] Lander’s collection of books on the Troad was totally destroyed. In 1840 Lander suffered a tragedy when his wife, Adele, died in her 40s, leaving three small children. He chose this time to settle his estate, making Frederick his legal heir, guardian of his children, and co-executor (along with himself).

Lander dedicated himself to the consular service, leaving the details of the estate and its reponsibilites to Frederick. The family grew wealthy on the fees paid by the ships they serviced. When Frank arrived in 1845[28] with his sister he had nothing much to do. By this time the family had a new library. Using its books Frank explored the Troad.[29] He and Lander became collectors. The women in the family took a supportive role as well.

Frederick Calvert[edit]

Lander died in 1846 of a fever endemic to the region, leaving Frederick as executor of the will and head of the family. In 1847 he assumed his uncle’s consular position. He was also an agent of Lloyd’s of London, which insured ship cargos. Despite Frank’s youth he began to play an important role in the family consular business, especially when Frederick was away.[30] A few years prior to the death of Lander, the population of Çanakkale was on the rise, from 10,000 in 1800 to 11,000 in 1842.[31] The British numbered about 40 families.[32] The increase in ship traffic meant prosperity for the Calverts, who expedited the ships of several nations, including the United States. They had other ambitions: James William Whittall, British consul in Smyrna, was spreading his doctrine of the “Trojan Colonization Society,” (never more than an idea) which was influential on the Calverts, whom he visited.[33]

Calvert investments in the Troad[edit]

In 1847 Frederick invested the profits of the family business in two large tracts in the Troad, amounting to many thousands of acres.[34][note 8] He founded a company, Calvert Bros. and Co., an “extended family company.”[35] The first purchase was a farm at Erenkőy, on the coast about half-way between Çanakkale and Troy. Frederick used it as a station for ships that could not make Çanakkale. The area was a target for Greek immigration. The family became money-lenders, lending only to Greeks at rates considered high (20%).[36]

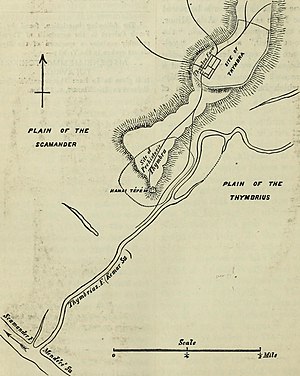

Frank Calvert’s sketch of the location of Thymbra Farm on the right bank of Kemer Creek (the ancient Thymbria), a right tributary of the Scamander. Using it one can easily locate the farm, which was confiscated by the Turkish government in 1939 (again, as it was Turkish headquarters in the Battle of Gallipoli) and remains a government farm. The modern buildings are next to the old farm on the east. The village was redistricted out of existence, but it was never there during the Calvert tenure.[37]

Frederick also bought a farm he intended to work, the Batak Farm (named for the Batak wetlands), later changed by Frank to Thymbra Farm, because he believed it was the site of Homeric Thymbra, after which the Thymbra Gate of Homeric Troy had been named. It was located at an abandoned village called Akça Köy, 4 mi. to the southeast of Hisarlik. The farm was the last of the village. It harvested and marketed the cups and acorns of Quercus macrolepis, the Valonia Oak, from which valonia, a compound used in dyeing and tanning, is extracted. The farm also raised cotton and wheat and bred horses. Frederick introduced the English plough and drained the wetlands. The farm eventually became famous as a way station for archaeologists and the home of the Calvert collection of antiquities, which Frank kept locked in a hidden room. The main house, featuring multiple guest bedrooms, was situated on a low ridge in a compound with several outbuildings. It was more of a manor, operated by farm workers and domestic servants.

In 1850–1852 Frederick solved the residence problem by having a mansion built for him in Çanakkale. Two Turkish houses were said to have been put together, but Turkish houses were required to be of wood. This one was of massive stone, which was permitted to foreigners, and was placed partly on fill jetting into the straits. It probably was the length of two Turkish houses. It remained the major building of the town until it was removed in 1942, due to earlier earthquake damage. The last of the Calvert descendants still in the region had ceded it to the town in 1939. The Town Hall was then built on the site. The mansion’s extensive gardens became a public park.[38]

The entire family of the times took up permanent residence in the mansion, which was never finished. It was almost always occupied by visitors and social events. The Calverts began a tour-guide business, conducting visitors throughout the Troad. Frank was the chief guide. The women held musicales and sang in the salons. The house attracted a stream of distinguished visitors, each with a theory about the location of Troy. Frederick, however, was not there for the opening of the house. After a fall from a horse in 1851, complications forced him to seek medical care in London for 18 months,[39] the first of a series of disasters. He was back by 1853.

Crimean War debacle[edit]

The Crimean War began in October 1853 and lasted through February 1856. Russia had arbitrarily occupied the Danube frontier of the Ottoman Empire including the Crimea, and Britain and France were providing military assistance to the Ottomans. The rear of the conflict was Istanbul and the Dardanelles. Britain relied heavily on the Levantine families for interfacing, intelligence, and guidance. Edmund Calvert was a British agent, but this was not Frederick’s calling. Not long after his return the initial British expeditionary force of 10,000 men was held up in ships in the straits, with no place to bivouac, no supplies, and a commissariat of four non-Turkish speakers.[40]

The British Army had reached a low point of efficiency since Wellington.[41] Although it was the responsibility of Parliament, the fact that the crown retained the prerogative of command made them hesitate to update it, for fear of its being used against them.[42] One of the major problems was the fragmentation of the administration into “a number of separate, distinct, and mutually independent authorities,” with little centralization.[43] There were always issues of who was in command and what they commanded. A Supply Corps as such did not exist. The immediate needs of the soldiers were supplied by the Commissariat Department, responsible to the Treasury.[44] Commissaries were assigned to units as needed, but they acted to solve supply problems ad hoc. They had no idea beforehand what the army needed, or what it had, or where it was located.

All the needs were given to contractors, who usually required money in advance. They were allowed to borrow from recommended banks. The Commissariat then paid the banks, but should it fail to do so, the debts were still incumbent on the debtors. Contractors were allowed to charge a percentage for their services, and also to include a percentage given to their suppliers as enticement. The Commissariat could thus build entire impromptu supply departments on the basis of immediate need, which is what Frederick did for them.[45]

The logistics problems were of the same type customarily undertaken by the consular staff, but of larger scale. Frederick was able to perform critical services for the army. Within several days he had all the men billeted ashore and had developed an organization of local suppliers on short notice. He secured their immediate attention by offering higher interest rates, to which the Commissary did not then object. He was so successful that he was given the problem of transporting men and supplies to the front.[note 9] For that he developed his own transport division of contractors paid as direct employees of his own company. He also advised the Medical Department in their choice of a site near Erenköy for a military hospital, named Renkioi Hospital.[45]

The army, arriving at Gallipoli in April 1854, did well at first, thanks to the efforts of Frederick Calvert and his peers. They were contracted by Deputy Assistant Commander-General of the Commissariat, John William Smith, on the instruction of the Commander-General, William Filder, who had given Smith their names in advance, especially that of Frederick Calvert. Frederick was waiting for the fleet in Gallipoli.[46][note 10] By June the army was doing badly. The Commissary seemed to have no understanding of military schedules. Needed supplies were not getting to their destinations for a number of reasons: perishables were spoiled through delay, cargos were lost or abandoned because there was no tracking system, or cut because a commissary speculated that they should be, etc. Frederick attempted to carry on by using his own resources in the expectation of collecting the money later by due process. By the end of the war his bill to the Commissary would be several thousand pounds. He had had to mortgage family properties in the Troad.[47]

By June it was obvious to Parliament that the cabinet position of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies was beyond the ability of only one minister. He was divested of his colonial duties, leaving him as Secretary of State for War,[48] but the Commissary was still not in his domain. In August, Frederick purchased the winter feed for the animals and left it on the dock at Salonica. Filder had adopted a policy of purchasing hay from London and having it pressed for land transport, even though chopped hay was readily available at a much cheaper price around the Dardanelles.[49] The Commissariat was supposed to inspect and accept it at Salonica, but the presses had been set up in the wrong location. By the time they were ready for the hay, most of it had spoiled, so they did not accept any of it.

The winter was especially severe. The animals starved, and without transport, so did the men, trying to make do without food, clothing, shelter or medical supplies.[50] Estimates of the death rate were as high as 35%, 42% in the field hospitals.[51] Florence Nightingale on the scene sounded the alarm to the general public. A scandal ensued; Prince Albert wrote to the Prime Minister. The folly of an army dying because not allowed to help itself while its Commissariat was not efficient enough to move even the minimum of supplies became manifest to the whole nation. In December Parliament placed the Commissariat under the army and opened an investigation.[52] In January, 1855, the government resigned, to be replaced shortly by another determined to do whatever was necessary to obtain a functional supply corps.[53]

The army found that it could not after all dispense with the Treasury or its system of payment. The first investigation went before Parliament in April, 1855. Filder’s defense was that he had conformed strictly to regulations,[note 11] and that he was not responsible for accidental events, which were “the visitations of God.”[54] John William Smith, Frederick’s handler in the Commissariat, included a number of favorable statements about him in the report, such as “the Commissariat would have been perfectly helpless without Mr. Calvert.”[55] Parliament exonerated the Commissariat, finding “no one in the Crimea was to blame.”[56]

Anticipating this result, the new government started a secret investigation of its own under J. McNeill, a civilian physician, and a milItary officer, Colonel A.M. Tulloch, which it outed in April after the acquittal. The new investigation lasted until January, 1856, and had nothing favorable to say. Losses higher than any battle could produce, and higher than those of any of the allies, were not to be dismissed as accidental.

The new commissioners attacked the system: “the system hitherto relied on as sufficient to provide for every emergency, had totally failed.”[57] The blow fell mainly on Filder. He had plenty of alternatives, Tulloch asserted, which he might have been expected to take. Chopped hay and cattle were readily and cheaply available in the Constantinople region. Filder had some cattle transports at his command in October. Once the supplies had been transported to the Crimea, they could have been carried inland by the troops themselves.[58] Of Filder, Tulloch said: “He was highly paid — not to do merely what he was ordered, but in the expectation that, when difficulties arose, he would show himself equal to the emergency, by … exercising that discretion and intelligence which the public has a right to expect ….”[59]

Filder was retired by the medical board because of age and sent home. Meanwhile the Commissary had introduced the word “profiteering” in a effort to cast the blame from itself. The decisions had been made by greedy contractors charging high interest rates, who had introduced delays to push the price up. John William Smith recanted what he had said about Frederick, now claiming that Frederick had put private interests before the public, without clarifying what he meant. The insinuation was enough to brand him as a profiteer.[60]. The entire Commissariat took it up as a theme, the banks refusing to honor contractor claims. Restrictions on loans tightened; cash flow problems developed. The inflated economy of the Troad began to collapse. The report was released in January. By then most contractors were in bankruptcy. British troops went home at the end of the war in February, having turned the Turkish merchants in the Troad against the English.

The cost of living remained high. Frederick was no longer trusted as a consular agent and had trouble finding work. His friend, John Brunton, head of the military hospital near Erenköy, was ordered to dismantle and sell the facility. He suggested that Brunton sell the medical supplies to him as surplus at a discount, so that he could recoup some of his estate by reselling them. Turning on him, as Smith had done, Brunton denounced him publicly.

Criminal charges were brought against Frederick for non-payment of debt to the War Office by the Supreme Consular Court of Istanbul in March, 1857. Due to difficulty in proving their case, it went on for months, being finally transferred to London,[61] where Frederick joined it in February, 1858. In 1859 he served a prison term of ten weeks on one debt. Subsequently the Foreign Office stepped in to manage his appeal. The military had not understood how the interest system worked. He won his case before Parliament, with commendation and thanks, and payment of the several thousand plus backpay and interest, arriving home 2.5 years after he had left it, to rescue the estate.[note 12]

The “Possidhon affair” and its aftermath[edit]

During the 1860s Frederick Calvert’s life and career were mainly consumed by a case of insurance fraud termed by the press the “Possidhon affair.” An attempt was made to defraud Lloyd’s of London of payments to an imaginary person claiming to own an imaginary ship, the Possidhon, that had gone to the bottom when its imaginary cargo burned, a claim made through Frederick. The perpetrators of the fraud, originally the witnesses of the fire, named Frederick as their ringleader. The trial was not a proper one, and Frederick was convicted on technicalities. He protested that he was the victim of an Ottoman frame-up, and was supported in that plea by his brother, Frank. There were a number of circumstances that remain historically unexplained. Modern historians who think he was guilty characterize him as a charismatic profiteer of shady ethics, while those who think he was innocent point to his patriotic motives in helping the British Army to the detriment of his own estate and his acquittal by Parliament.

Having returned from London in October, 1860, with enough money to restore the family estate, Frederick now turned his attention to the family avocation, archaeology, rejecting a lucrative job offer as a Consul in Syria.[62] Frank, now age 32, had long been the master of the estate and of the business. By this time he was also a skilled and respected archaeologist. He spent all of his spare time investigating and excavating the numerous habitation and burial sites of the Troad. He was an invaluable consultant to specialists in many areas from plants to coins. Frederick joined him in this life by choice. For a few years he was able to work with Frank in expanding Lander’s library and collection, and in exploring and excavating ancient sites.

In 1846 Frederick married Eveline, an heiress of the wealthy Abbotts, owners of some mines in Turkey. They had at least five known children.

Frederick’s wife’s uncle, William Abbott, had gone with him to London, where they purchased a house for mutual residence. Frederick set him up in a few different businesses, the last being Abbott Brothers, dealers in firewood. His son, however, William George Abbott, a junior partner of Frederick in the consular business, remained in the Dardanelles to handle business there as acting consul.[note 13] In January, 1861, the consular office was approached by a Turkish merchant, Hussein Aga, requesting 12000 £. ($15384.62} of insurance from Lloyd’s on the cargo of the Possidhon, which was olive oil. He claimed to be a broker marketing the oil produced by certain pashas and now wished to sell it in Britain.[citation needed]

Frederick requested William in London to borrow money as Abbot Brothers to finance the premiums.[63] The debt was to be paid when the cargo was sold. It isn’t clear whether Abbott was to sell it, and if so, in whose name. The cargo, being insured by him, was consigned to him. A loan of 1500 £ ($1923.08) was effected on April 11, and the premiums were paid.

The ship, cleared to sail from Edremit to Britain by Frederick’s office on April 4, sailed on the 6th. Frederick was to have inspected it before issuing the clearance, but he did not. On April 28 Frederick notified Lloyd’s by telegram that the vessel had been seen burning off Lemnos in a heavy wind on April 8, which is peculiar, because it ought to have been far from Lemnos by then. When it had not arrived months later the creditors for the premiums requested their money. Frederick submitted a claim through Abbott for a total loss. He suggested Greek pirates and collaboration of the crew as causes, implicating Hussein Aga, who had not been seen since then. Lloyd’s requested documents giving testimony of the loss, turning the case over to Lloyd’s Salvage Association.

Frederick forwarded to Abbott in London four affidavits from British consular agents on Tenedos and Samos of visual sightings of the ship. Conspicuously absent were any Turkish documents that should have been examined before permission to sail was granted. An investigator from Lloyd’s Salvage working from Constantinople finding no record of either Aga or the ship concluded to a fraud. Simultaneously Frederick, conducting his own investigation, reached a similar conclusion. He had been duped by a person pretending to be a fictional Hussein Aga. The witnesses produced a confession, naming Frederick as mastermind of the scheme. The Salvage Association turned the matter over to the Foreign Office. M. Tolmides, consular agent at Tenedos, admitted to signing the affidavits. His defense was that he had given Frederick blank signed forms.

The Foreign Office issued a public statement questioning Frederick’s credibility. He requested permission to leave his post to travel to London to defend himself. Permission was denied. On April 30 he issued a statement that he had been set up and was being framed by an unknown agent, for whom he was conducting an unsuccessful search at Smyrna. He found some support in the British ambassador, Henry Bulwer, 1st Baron Dalling and Bulwer, a liberal and a freemason, who accepted him as credible, and noted the hostility of Turkish officialdom against him. However, unless Frederick could produce some evidence of the conspiracy, he affirmed, he would officially have to side with the insurance company. The matter became international. Turkish harbor officials claimed, via Lloyd’s agents, that Frederick had submitted forged documents to them. The Ottoman Porte complained. The Prince of Wales scheduled a visit. Fredrick was going to be brought before a consular court, an agency with a reputation for corruption; in particular, bribability.[citation needed]

Frank Calvert[edit]

Due to the publicity skills of Heinrich Schliemann and the public discreditation of Frederick as a convicted felon, the contributions mainly of Frank to the excavation of Troy remained unknown and unappreciated until the end of the 20th century, when the Calverts became an object of special study. A number of misunderstandings still cling to them. One is that Schliemann discovered Troy on land he had the foresight to purchase from the Calverts. To the contrary, it was Frank who convinced Frederick to purchase Hissarlik as the probable site of Troy, and Frank who convinced Schliemann that it was there, and to partner with him in its excavation.[64] The Calverts did not hand anything over; they remained on site excavating with him and attempting to advise and manage him. Frank was often a sharp critic. Frank is sometimes called “self-taught.” Educationally this was not true. He did not attend university, but there would have been no point, as archaeology was not yet taught there. Frank was the first modern (19th century) to excavate in the Troad.[65] He knew more than all the visitors he tutored.

In 1866, Frank Calvert, the brother of the United States’ consular agent in the region, made extensive surveys and published in scholarly journals his identification of the hill of New Ilium (which was on farmland owned by his family) on the same site. The hill, near the city of Çanakkale, was known as Hisarlik.[66]

The British diplomat, considered a pioneer for the contributions he made to the archaeology of Troy, spent more than 60 years in the Troad (modern day Biga peninsula, Turkey) conducting field work.[67] As Calvert was a principal authority on field archaeology in the region, his findings supplied evidence that Homeric Troy might have existed on the hill, and played a major role in convincing Heinrich Schliemann to dig at Hisarlik.[21]

The Schliemanns[edit]

In 1868, German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann visited Calvert and secured permission to excavate Hisarlik. He sincerely believed that the literary events of the works of Homer could be verified archaeologically. A divorced man in his 40s who had acquired some wealth as a merchant in Russia, he decided to use the wealth to follow his boyhood interest in finding and verifying the city of Troy. Leaving his former life behind, he advertised for a wife whose skills and interest were on a par with his own, Sophia. She was 17 at the time but together they excavated Troy, sparing no expense.

Heinrich began by excavating a trench across the mound of Hisarlik to the depth of the settlements, today called “Schliemann’s Trench.” In 1871–73 and 1878–79, he discovered the ruins of a series of ancient cities dating from the Bronze Age to the Roman period. He declared one of these cities—at first Troy I, later Troy II—to be the city of Troy, and this identification was widely accepted at that time. Subsequent archaeologists at the site were to revise the date upward; nevertheless, the main identification of Troy as the city of the Iliad, and the scheme of the layers, have been kept.

Some of Schliemann’s portable finds at Hisarlik have become known as Priam’s Treasure, such as the jewelry photographed displayed on Sophia. The artifacts were acquired from him by the Berlin museums. As Sophia matured she became an invaluable assistant to Schliemann, whom he employed especially in social situations requiring the use of modern Greek. After his death she became caretaker of his funds and publications, continuing to advocate for his beliefs. She was a respected socialite in Athens.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld[edit]

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1893–94) joined the excavation at the request of Schliemann. After Schliemann left, he inherited the management of it. His chief contribution was the detailing of Troy VI. He published his findings separately.[68]

University of Cincinnati[edit]

Carl Blegen[edit]

Carl Blegen, professor at the University of Cincinnati, managed the site 1932–38. These archaeologists, though following Schliemann’s lead, added a professional approach not available to Schliemann. He showed that there were at least nine cities. In his research, Blegen came to a conclusion that Troy’s nine levels could be further divided into forty-six sublevels,[69] which he published in his main report.[70]

Korfmann[edit]

In 1988, excavations were resumed by a team from the University of Tübingen and the University of Cincinnati under the direction of Professor Manfred Korfmann, with Professor Brian Rose overseeing Post-Bronze Age (Greek, Roman, Byzantine) excavation along the coast of the Aegean Sea at the Bay of Troy. Possible evidence of a battle was found in the form of bronze arrowheads and fire-damaged human remains buried in layers dated to the early 12th century BC. The question of Troy’s status in the Bronze-Age world has been the subject of a sometimes acerbic debate between Korfmann and the Tübingen historian Frank Kolb in 2001–2002.

Korfmann proposed that the location of the city (close to the Dardanelles) indicated a commercially oriented city that would have been at the center of a vibrant trade between the Black Sea, Aegean, Anatolian and Eastern Mediterranean regions. Kolb disputed this thesis, calling it “unfounded” in a 2004 paper. He argues that archaeological evidence shows that economic trade during the Late Bronze Age was quite limited in the Aegean region compared with later periods in antiquity. On the other hand, the Eastern Mediterranean economy was more active during this time, allowing for commercial cities to develop only in the Levant. Kolb also noted the lack of evidence for trade with the Hittite Empire.[71]

In August 1993, following a magnetic imaging survey of the fields below the fort, a deep ditch was located and excavated among the ruins of a later Greek and Roman city. Remains found in the ditch were dated to the late Bronze Age, the alleged time of Homeric Troy. Among these remains are arrowheads and charred remains.[72] It is claimed by Korfmann that the ditch may have once marked the outer defenses of a much larger city than had previously been suspected. In the olive groves surrounding the citadel, there are portions of land that were difficult to plow, suggesting that there are undiscovered portions of the city lying there. The latter city has been dated by his team to about 1250 BC, and it has been also suggested—based on recent archeological evidence uncovered by Professor Manfred Korfmann’s team—that this was indeed the Homeric city of Troy.

Becker[edit]

Helmut Becker utilized magnetometry in the area surrounding Hisarlik. He was conducting an excavation in 1992 to locate outer walls of the ancient city. Becker used a caesium magnetometer. In his and his team’s search, they discovered a “‘burnt mudbrick wall’ about 400 metres south of the Troy VI fortress wall.”[73] After dating their find, it was deemed to have been from the late Bronze Age, which would put it either in Troy VI or early Troy VII. This discovery of an outer wall away from the tell proves that Troy could have housed many more inhabitants than Schliemann originally thought.

Recent developments[edit]

In summer 2006, the excavations continued under the direction of Korfmann’s colleague Ernst Pernicka, with a new digging permit.[74]

In 2013, an international team made up of cross-disciplinary experts led by William Aylward, an archaeologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was to carry out new excavations. This activity was to be conducted under the auspices of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University and was to use the new technique of “molecular archaeology”.[75] A few days before the Wisconsin team was to leave, Turkey cancelled about 100 excavation permits, including Wisconsin’s.[76]

In March 2014, it was announced that a new excavation would take place to be sponsored by a private company and carried out by Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University. This will be the first Turkish team to excavate and is planned as a 12-month excavation led by associate professor Rüstem Aslan. The University’s rector stated that “Pieces unearthed in Troy will contribute to Çanakkale’s culture and tourism. Maybe it will become one of Turkey’s most important frequented historical places.”[77]

Troy Historical National Park[edit]

The Turkish government created the Historical National Park at Troy on September 30, 1996. It contains 136 square kilometres (53 sq mi) to include Troy and its vicinity, centered on Troy.[78] The purpose of the park is to protect the historical sites and monuments within it, as well as the ecology of the region. In 1998 the park was accepted as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 2015 a Term Development Revision Plan was applied to the park. Its intent was to develop the park into a major tourist site.[79] Plans included marketing research to determine the features most of interest to the public, the training of park personnel in tourism management, and the construction of campsites and facilities for those making day trips. These latter were concentrated in the village of Tevfikiye, which shares Troy Ridge with Troy.

Public access to the ancient site is along the road from the vicinity of the museum in Tevfikiye to the east side of Hisarlik. Some parking is available. Typically visitors come by bus, which disembarks its passengers into a large plaza ornamented with flowers and trees and some objects from the excavation. In its square is a large wooden horse monument, with a ladder and internal chambers for use of the public. Bordering the square is the gate to the site. The public passes through turnstiles. Admission is usually not free. Within the site, the visitors tour the features on dirt roads or for access to more precipitous features on railed boardwalks. There are many overlooks with multilingual boards explaining the feature. Most are outdoors, but a permanent canopy covers the site of an early megaron and wall.

UNESCO World Heritage Site[edit]

The archaeological site of Troy was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1998.

For a site to be named a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it must be claimed to have Outstanding Universal Value. This means that it must be historically, culturally, or scientifically significant to all peoples of the world in some manner. According to the UNESCO site on Troy, its historical significance was gained because the site displays some of the “first contact between…Anatolia and the Mediterranean world”.[80] The site’s cultural significance is gained from the multitudes of literature regarding the famed city and history over centuries. Many of the structures dating to the Bronze Age and the Roman and Greek periods are still standing at Hisarlik. These give archeological significance to the site as well.

Troy Museum[edit]

In 2018 the Troy Museum (Turkish Troya Müzesi) was opened at Tevfikiye village 800 metres (870 yd) east of the excavation. A design contest for the architecture had been won by Yalin Mimarlik in 2011. The cube-shaped building with extensive underground galleries holds more than 40,000 portable artifacts, 2000 of which are on display. Artifacts were moved here from a few other former museums in the region. The range is the entire prehistoric Troad. Displays are multi-lingual. In many cases the original contexts are reproduced.

Priam’s Treasure[edit]

Priam’s Treasure, which Heinrich Schliemann claimed to have found at Troy

Some of the most notable artifacts uncovered at Hisarlik are known as Priam’s Treasure. Most of these pieces were crafted from gold and other precious metals. Heinrich Schliemann put this assemblage together from his first excavation site, which he thought to be the remains of Homeric Troy. He gave them this name after King Priam, who is said in the ancient literature to have ruled during the Trojan War. However, the site that housed the treasure was later identified as Troy II, whereas Priam’s Troy would most likely have been Troy VIIa (Blegen) or Troy VIi (Korfmann).[note 14] One of the most famous photographs of Sophia made not long after the discovery depicts her wearing a golden headdress, which is known as the “Jewels of Helen” (see under Schliemann above).

Other pieces that are a part of this collection are:

- copper artifacts – a shield, cauldron, axeheads, lance heads, daggers, etc.

- silver artifacts – vases, goblets, knife blades, etc.

- gold artifacts – bottle, cups, rings, buttons, bracelets, etc.

- terra cotta goblets

- artifacts with a combination of precious metals

Fortifications of the city[edit]

Literary Troy was characterized by high walls and towers, summarized by the epithet “lofty Ilium.”[81] Some other epithets were “well-walled,” “with lofty gates,” “with fine towers.”[82] Any archaeological candidate for being the literary city would therefore have to show evidence for the walls and towers. Schliemann’s Troy fits this qualification very well. High walls and towers are in evidence at every hand. Hisarlik, the name of the hill on which Troy is situated, is Turkish for “the fortress.”[83]

The walls of Troy, first erected in the Bronze Age between at least 3000 and 2600 BC, were its main defense, as is true of almost any ancient city of urban size. Whether Troy Zero featured walls is not yet known. Some of the known walls were placed on virgin soil (see the archaeology section below). The early date of the walls suggests that defense was important and warfare was a looming possibility right from the beginning.

The walls surround the citadel, extending for several hundred meters, and at the time they were built were over 17 feet (5.2 m) tall.[84] They were made of limestone, with watchtowers and brick ramparts, or elevated mounds that served as protective barriers.[84]

The second run of excavations, under Korfmann, revealed that the walls of the first run were not the entire suite of walls for the city, and only partially represent the citadel. According to Korfmann, “There was also a lower city that went with the Late Bronze Age Troja,…1750-1200 BCE.”[85] This city had a perimeter 0f 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) end enclosed an area 16 times that of the citadel. It was protected by a ditch surmounted by a wall of mud brick and wood.[86] Moreover, the citadel walls were surmounted by structures of mud brick. The stone part of the walls currently in evidence were “…five meters thick and at least eight meters high – and over that a mudbrick superstructure several meters high…,” which totals to about 15 metres (49 ft) for the citadel walls at about the time of the Trojan War. The present-day walls of Troy, then, portray little of the ancient city’s appearance, any more than bare foundations characterize a building.

- Foundations of the citadel fortifications

-

South gate wall and tower, Early Troy I through Middle Troy II[87]

Prehistory of Troy[edit]

| Illustration by Bibi Saint-Pol[88] | |

A diachronic plan superposing several of the citadels placed successively on the hill of Hisarlik, each termed by Schliemann a “city.” The layers and therefore the relative time periods are shown in different colors. The author provides a second legend identifying the features marked by the small numbers on the overlay: 1: Gate 2: City Wall 3: Megarons 4: FN Gate 5: FO Gate 6: FM Gate and Ramp 7: FJ Gate 8: City Wall 9: Megarons 10: City Wall 11: VI. S Gate 12: VI. H Tower 13: VI. R Gate 14: VI. G Tower 15: Well-Cistern 16: VI. T Dardanos Gate 17: VI. I Tower 18: VI. U Gate 19: VI. A House 20: VI. M Palace-Storage House 21: Pillar House 22: VI. F House with columns 23: VI. C House 24: VI. E House 25: VII. Storage 26: Temple of Athena 27: Entrance to the Temple (Propylaeum) 28: Outer Court Wall 29: Inner Court Wall 30: Holy Place 31: Water Work 32: Parliament (Bouleuterion) 33: Odeon 34: Roman Bath |

|

What Schliemann actually found as he excavated the hill of Hisarlik somewhat haphazardly were contexts in the soil parallel to the contexts of geologic layers in rock. Exposed rock displays layers of a similar composition and fossil content within a layer discontinuous with other layers above and below it. The layer represents an accumulation of detritus over a continuous time, different from the times of the other layers.

Similarly Schliemann found layers of distinctive soil each containing more or less distinctive artifacts differing often markedly from other layers. He had no ready explanation for the discontinuity between layers, such as “destruction,” although this interpretation has sometimes been applied. Presumably “destruction” is to be interpreted to mean some sort of malicious event perpetrated by humans or a natural disaster, such as an earthquake. In most cases no such disaster can be proved. On the contrary, the “many layers illustrate the gradual development of civilization in northwestern Asia Minor.”[84][note 15]

The discontinuities of culture in different layers might be explained in a number of ways. A settlement might have been abandoned for peaceful reasons, or it might have undergone a renovation phase. These are hypotheses that must be ruled in or ruled out by evidence, or simply be left unruled until evidence should be discovered.

What Schliemann found is that the area now called “the citadel” or “the upper city” was apparently placed on virgin soil. It was protected by fortifications right from the start. The layering effect was caused in part by the placement of new fortifications and new houses over the old. Schliemann called these fortified enclosures “cities” (rightly or wrongly). In his mind the site was composed of successive cities. Like everyone else, he speculated whether a new city represented a different population, and what its relationship to the old was. He numbered the cities I, II, etc., I being on the bottom. Subsequent archaeologists turned the “cities” into layers (rightly or wrongly), named according to the new archaeological naming conventions then being developed. The layers of ruins in the citadel at Hisarlik are numbered Troy I – Troy IX, with various subdivisions.

| The Layers of Troy | |

Until the late 20th century, these layers represented only the layers on the hill of Hisarlik. Archaeologists following Schliemann picked up the trail of his researches adopting the same fundamental assumptions, culminating in the work and writings of Carl Blegen in the mid-20th century. In a definitive work, Troy and the Trojans, he summarized the layers names and the dates he had adopted for them.[89] Without further excavation, Blegen’s was the last word. There were, however, some persistent criticisms not answered to general satisfaction. Hisarlik, about the size of a football field, was not large enough to have been the mighty city of history. It was also far inland, yet the general historical tradition suggested it must have been close to the sea.

The issues finally devolved on the necessity for further excavation, which was undertaken by Korfmann starting 1988. He concentrated on the Roman city, which was not suspected as being over Bronze Age remains. A Bronze Age city, at low elevations, was discovered beneath it. As it is unlikely that there were two Troys side by side, the lower city must have been the main seat of residence, to which the upper city served as citadel. Korfman now referred to the layers of the lower city as associated with the layers of the citadel. The same layering scheme was applicable. The lower city was many times the size of the citadel, answering the size objection.

The view from Schliemann’s Trench at Hisarlık across the modern plain of Ilium to the Aegean Sea. The suburbs of Çanakkale are visible in the distance. The foreground shows foundations of Troy I houses. During the early Troy periods, nearly the entire plain was an inlet of the sea.

Meanwhile independent geoarchaeological research conducted by taking ground cores over a wide area of the Troad were demonstrating that, in the time of Troy I, “… the sea was right at the foot of ‘Schliemann’s Trench’ during the earliest periods of Troja.”[90] A few thousand years earlier the ridge of Troy was partly surrounded by an inlet of the sea occupying the now agricultural area of the lower Scamander River. Troy was founded as an apparently maritime city on the shore of this inlet, which persisted throughout the early layers and was present to a lesser degree, farther away, subsequently. The harbor at Troy, however, was always small, shallow, and partially blocked by wetlands. It was never a “great harbor” able to collect maritime traffic through the Dardanelles.[91] The current water table depends on the degree of irrigation of the now agricultural lands. Trench flooding has slowed investigation of the lower levels in the lower city.

The whole course of archaeological investigation at Troy has resulted in no single chronological table of layers. Moreover, due to limitations on the accuracy of C14 dating, the tables remain relative; i.e., absolute, or calendar dates, cannot be precisely assigned. In regions of the Earth where both history and C14 dating are available, there is often a gap between them, termed by Renfrew a chronological or archaeological “fault line.” The two models, historical and archaeological, do not correspond, just as the contexts on either side of a geologic fault line do not correspond. “This line divides all Europe except the Aegean from the Near East.”[92]

Table of layers[edit]

The table below concentrates on two systems of dates: Blegen’s from Troy and the Trojans,[89][note 16], representing the last of the trend from Schliemann to the mid-20th century, and Korfmann’s, from Troia in Light of New Research in the early years of the 21st century, after he had had a chance to establish a new trend and new excavations.[93]

Prior to Korfmann’s excavations, the nine-layer model was considered comprehensive of all the material at Troy. Korfmann discovered that the city was not placed on virgin soil, as Schliemann had concluded. There is no reason not to think that, in the areas he tested, Schliemann did find that Troy I was on virgin soil. Korfmann discovered a layer previous to Troy I under a gate to Troy II. He dated it 3500 BC to 2920 BC, but did not assign a name. The current director of excavation at Troy, Rüstem Aslan, is calling it Troy 0 (zero).[94] Roman numerals have no zero, but zero is one number less than I.

Troy 0 has been omitted from the table below, due to the uncertainty of its general status. Archaeologists at the site before Korfmann had thought that Troy I began with the Bronze Age at 3000 BC. Troy zero is before this date. The remains of the layer are not very substantial. Whether the layer is to be counted as part of the preceding Chalcolithic, or whether the dates of the Bronze Age are to be changed, has not been decided through the regular channel of journal articles. One 2016 PhD Thesis complained: “… the stratigraphic sequence of the renewed excavations is presented differently by different collaborators of Korfmann … So, until an agreed stratigraphy of Korfmann’s cycle is published, the employment of Troy as a yardstick for the whole of the Anatolian EBA remains problematic.”[95][note 17]

For example, in Korfmann 2003, p. 31 Korfmann elaborates beyond the chronology of Cobet’s table to make new proposals regarding the layer, Troy VIIa (which he also presents in the Guidebook): “Troia VIIa should be assigned culturally to Troia VI,” asserting that “there were no substantial differences in the material culture between the two periods.” He suggests that Dőrpfeld’s classification of the material subsequently in VIIa as VIi should be restored, claiming that, regarding the details, Blegen had been “entirely in agreement” even though his chronology featured Troy VIIa.[note 14] He then laments “the old terminology has, unfortunately, been retained. Confusion is to be avoided at all costs.” As this view has not yet been tested in the journals and is not universal, it is mainly omitted from the table (Cobet’s chart, however, includes Korfmann’s VIIb 3.) This new and yet unresolved material, including Troy Zero, may, however, be included in the sections and links below reporting on specific layers

Korfmann also found that Troy IX was not the end of the settlements. Regardless of whether the city was abandoned at 450 AD, a population was back for the Middle Ages, which, for those times, was under the Byzantine Empire. As with Troy Zero, no conventional scholarly classification has been tested in the journals. The literature mentions Troy X, and even Troy XI, without solid definition. The table below therefore omits them.

The sequence of archaeological layering at one site evidences the relative positions of the corresponding periods at that site; however, these layers often have a position relative to periods at other sites. It is possible to define relative periods over a wide region of sites and for a larger slice of time. Determining wider correspondences is a major objective of archaeology. The establishment of a “yardstick,” or reliable sequence, such as the elusive one mentioned above, is a desirable outcome of archaeological analysis.

The table below states the broader connections under “General Period.” It references primarily the chronologies presented in the educational site created and maintained by Jeremy Rutter and team and published by Dartmouth College, entitled Aegean Prehistoric Archaeology.[96][note 18] The time period is generally “the Bronze Age,” which has an early (EB or EBA), a middle (MB or MBA), and a late (LB or LBA). The sites are distributed over Crete (“Minoan,” or M), the Cyclades (“Cycladic,” or C), the Greek mainland (“Helladic,” or H), and Western Turkey (“Western Anatolian,” no abbreviation).

| Layer | Start (Blegen) |

Start (Korfmann) |

End (Blegen) |

End (Korfmann) |

General Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troy I | 3000 BC | 2920 BC | 2500 BC | 2550 BC | Western Anatolian EB 1 late |

| Troy II | 2500 BC | 2550 BC | 2200 BC | 2250 BC | Western Anatolian EB 2 |

| Troy III | 2200 BC | 2250 BC | 2050 BC | 2100 BC | Western Anatolian EB 3 early |

| Troy IV | 2050 BC | 2100 BC | 1900 BC | 1900 BC | Western Anatolian EB 3 middle |

| Troy V | 1900 BC | 1900 BC | 1800 BC | 1700 BC | Western Anatolian EB 3 late |

| Troy VI | 1800 BC | 1700 BC | 1300 BC | 1300 BC | West. Anat. MBA (Troy VI early) West. Anat. LBA (Troy VI middle and late) |

| Troy VIIa | 1300 BC | 1300 BC | 1260 BC | 1190 BC | Western Anatolian LBA |

| Troy VIIb 1 | 1260 BC | 1190 BC | 1190 BC | 1120 BC | Western Anatolian LBA |

| Troy VIIb 2 | 1190 BC | 1120 BC | 1100 BC | 1020 BC | Western Anatolian LBA |

| Troy VIIb 3 | 1020 BC | 950 BC | Iron Age – Dark Age Troy | ||

| Troy VIII | 700 BC | 750 BC | 85 BC | Iron Age – Classical and Hellenistic Troy | |

| Troy IX | 85 BC | 450 AD | Iron Age – Roman Troy |

Troy I–V[edit]

The first city on the site was founded in the 3rd millennium BC. During the Bronze Age, the site seems to have been a flourishing mercantile city, since its location allowed for complete control of the Dardanelles, through which every merchant ship from the Aegean Sea heading for the Black Sea had to pass. Cities to the east of Troy were destroyed, and although Troy was not burned, the next period shows a change of culture indicating a new people had taken over Troy.[97] The first phase of the city is characterized by a smaller citadel, around 300 ft in diameter, with 20 rectangular houses surrounded by massive walls, towers, and gateways.[84] Troy II doubled in size and had a lower town and the upper citadel, with the walls protecting the upper acropolis which housed the megaron-style palace for the king.[98] The second phase was destroyed by a large fire, but the Trojans rebuilt, creating a fortified citadel larger than Troy II, but which had smaller and more condensed houses, suggesting an economic decline.[84] This trend of making a larger circuit, or extent of the walls, continued with each rebuild, for Troy III, IV, and V. Therefore, even in the face of economic troubles, the walls remained as elaborate as before, indicating their focus on defense and protection.

Schliemann’s Troy II[edit]

When Schliemann came across Troy II, in 1871, he believed he had found Homer’s city. Schliemann and his team unearthed a large feature he dubbed the Scaean Gate, a western gate unlike the three previously found leading to the Pergamos.[99] This gate, as he describes, was the gate that Homer had featured. As Schliemann states in his publication Troja: “I have proved that in a remote antiquity there was in the plain of Troy a large city, destroyed of old by a fearful catastrophe, which had on the hill of Hisarlık only its Acropolis with its temples and a few other large edifices, southerly, and westerly direction on the site of the later Ilium; and that, consequently, this city answers perfectly to the Homeric description of the sacred site of Ilios.”[100]Also, he uncovered what he referred to as The Palace of Priam, after the king during the Trojan War.[101] This reference is incorrect because Priam lived nearly a thousand years after Troy II.

Troy VI and VII[edit]

The suicide of Ajax (from a calyx-krater, 400–350 BC, Vulci)

Troy VI and VII date to the Late Bronze Age, and are thus considered likely candidates for the Troy of Homer. Troy VI was a large and significant city, home to at least 5,000 people with foreign contacts in Anatolia and the Aegean.[102] Troy VI can be characterized by the construction of enormous pillars at the south gate, which serve no structural purpose. These pillars have been interpreted as symbols for the religious cults of the city.[103] Another characterizing feature of Troy VI are the tightly packed houses near the Citadel and construction of many cobble streets. Although only few homes could be uncovered, this is due to reconstruction of Troy VIIa over the tops of them.[104]

Researchers have debated the extent to which Troy VI was a major player in Bronze Age international trade. On one hand, hundreds of contemporary shipwrecks have been found off the coast of Turkey. Goods discovered in these wrecks included copper and tin ingots, bronze tools and weapons, ebony, ivory, ostrich egg shells, jewelry, and pottery from across the Mediterranean.[105] However, Troy is just north of most major long-distance trade routes and there is little direct evidence at the site itself.[105] Researchers have also debated the extent to which Troy VI was Anatolian-oriented or Aegean-oriented. Evidence for an Anatolian orientation includes pottery styles, architectural designs, and burial practices which was not standard in the Mycenaean world. Moreover, the only Bronze Age writing found at the site is written in hieroglyphic Luwian.[102] However, Mycenaean pottery has been found at Troy VI, showing that it did trade with the Greeks and the Aegean. Furthermore, there were cremation burials discovered 400m south of the citadel wall.[relevant? ] This provided evidence of a small lower city south of the Hellenistic city walls. Although the size of this city is unknown due to erosion and regular building activities, there is significant evidence that was uncovered by Blegen in 1953 during an excavation of the site. This evidence included settlements just above bedrock and a ditch thought to be used for defense. Furthermore, the small settlement itself, south of the wall, could have also been used as an obstacle to defend the main city walls and the citadel.[106]

Troy VI was destroyed around 1250 BC, probably by an earthquake. Only a single arrowhead was found in this layer, and no remains of bodies.[citation needed] However, the town quickly recovered and was rebuilt in a layout that was more orderly.[citation needed] This rebuild continued the trend of having a heavily fortified citadel to preserve the outer rim of the city in the face of earthquakes and sieges of the central city.[98] The city was rebuilt as Troy VIIa, withmost of the population moving within the walls of the citadel. Archaeologists have interpreted this as a reaction to external threats such as the Mycenaeans.[107] Excavating and periodizing these layers has proved difficult since Troy VII was built directly over Troy VI, often incorporating the foundations of it buildings.[108] Troy VIIa is an often cited candidate for the Troy of Homer, since there is evidence that it was destroyed deliberately in an act of war.[109][110]

Calvert’s Thousand-Year Gap[edit]

Initially, the layers of Troy VI and VII were overlooked entirely, because Schliemann favoured the burnt city of Troy II. It was not until the need to close “Calvert’s Thousand Year Gap” arose—from Dörpfeld’s discovery of Troy VI—that archaeology turned away from Schliemann’s Troy and began working towards finding Homeric Troy once more.[111]

“Calvert’s Thousand Year Gap” (1800–800 BC) was a period not accounted for by Schliemann’s archaeology and thus constituted a hole in the Trojan timeline. In Homer’s description of the city, a section of one side of the wall is said to be weaker than the rest.[112] During his excavation of more than three hundred yards of the wall, Dörpfeld came across a section very closely resembling the Homeric description of the weaker section.[113] Dörpfeld was convinced he had found the walls of Homer’s city, and now he would excavate the city itself. Within the walls of this stratum (Troy VI), much Mycenaean pottery dating from Late Helladic (LH) periods III A and III B (c. 1400–c. 1200 BC) was uncovered, suggesting a relation between the Trojans and Mycenaeans. The great tower along the walls seemed likely to be the “Great Tower of Ilios”.[114]

The evidence seemed to indicate that Dörpfeld had stumbled upon Ilios, the city of Homer’s epics. Schliemann himself had conceded that Troy VI was more likely to be the Homeric city, but he never published anything stating so.[115] The only counter-argument, confirmed initially by Dörpfeld (who was as passionate as Schliemann about finding Troy), was that the city appeared to have been destroyed by an earthquake, not by men.[116] There was little doubt that this was the Troy of which the Mycenaeans would have known.[117]

Historical Troy[edit]

The archaeologists of Troy concerned themselves mainly with prehistory; however, not all the archaeology performed there falls into the category of prehistoric archaeology. Troy VIII and Troy IX are dated to historical periods. Historical archaeology illuminates history. In the LBA records mentioning Troy begin to appear in other cultures. This type of evidence is termed protohistory. The literary characters and events must be classified as legendary. Prehistoric Troy is also legendary Troy. The legends are not history or protohistory, as they are not records. It was the question of their historicity that attracted the interest of such archaeologists as Calvert and Schliemann. After many decades of archaeology, there are still no answers. There is still a “fault line” between history or legend and archaeology.

Troy in Late Bronze Age Hittite and Egyptian records[edit]

If Homeric Troy is not a fantasy woven in the 8th century by Greek oral poets passing on a tradition of innovating new poems at festivals, as most archaeologists hoped it was not, then the question must be asked, “what archaeological level represents Homeric Troy?” Only two credible answers are available, which are the same answer: Troy VIIa in the Blegen scheme,[118] identical to Troy VIi in the scheme suggested by Korfmann.[119] After an earthquake brought down the walls of the city at its floruit about 1300 BC, the same people rebuilt the city even more magnificent than before. This event is considered the start of the LBA, and Homeric Troy is considered to be LBA Troy.

Both Blegen and Korfmann endorse a starting date of about 1300 BC. Blegen has it ending early at 1260 BC,[note 19] but Korfmann runs it up to 1190 BC (or 1180 BC elsewhere). He abolishes VIIa, and substitutes for it VIi, more in keeping with the splendor of VI; after all, they were the same people. He estimates the population at 10,000.[120] The end of the period is marked by weapons left laying around, skeletons, and burnt objects, considered the result of the Trojan War. Coincidentally this is the very period referenced by Egyptian and Hittite records of Troy. They hold out some hope of a protohistorical connection.

In the 1920s, the Swiss scholar Emil Forrer proposed that the placenames Wilusa and Taruisa found in Hittite texts should be identified with Ilion and Troia, respectively.[121] He further noted that the name of Alaksandu, a king of Wilusa mentioned in a Hittite treaty, is quite similar to Homer’s Paris, whose birthname was Alexandros. These identifications were rejected by many scholars as being improbable or at least unprovable. However, Trevor Bryce championed them in his 1998 book The Kingdom of the Hittites, citing a piece of the Manapa-Tarhunda letter referring to the kingdom of Wilusa as beyond the land of the Seha River (the classical Caicus and modern Bakırçay) and near the land of “Lazpa” (Lesbos).

The excavation of the lower city uncovered a water distribution system containing 160 metres (520 ft) of tunnels tapping sources higher up on the ridge. Dates from the floor deposits obtained by the Uranium-thorium dating method indicate that water was flowing through the tunnels “as early as the third millenium BC;” thus the early city made sure that it had an internal water supply.[122] In 1280 BC a treaty between the reigning monarchs of the Hittite and Trojan states, Muwatalli II and Alaksandu of Wilusa respectively, invoked the water god, KASKAL_KUR, who was associated with an underground tunnel, adding weight to the theory that Wilusa is identical to archaeological Troy.

Among the documents mentioning Troy are the Tawagalawa letter (CTH 181) was found to document an unnamed Hittite king’s correspondence to the king of the Ahhiyawa, referring to an earlier “Wilusa episode” involving hostility on the part of the Ahhiyawa. The Hittite king was long held to be Mursili II (c. 1321–1296), but, since the 1980s, his son Hattusili III (1265–1240) is commonly preferred, although his other son Muwatalli (c. 1296–1272) remains a possibility.

Inscriptions of the New Kingdom of Egypt also record a nation T-R-S as one of the Sea Peoples who attacked Egypt during the XIX and XX Dynasties. An inscription at Deir el-Medina records a victory of Ramesses III over the Sea Peoples, including one named “Tursha” (Egyptian: [twrš3]). It is probably the same as the earlier “Teresh” (Egyptian: [trš.w]) on the stele commemorating Merneptah‘s victory in a Libyan campaign around 1220 BC.

The identifications of Wilusa with Troy and of the Ahhiyawa with Homer’s Achaeans remain somewhat controversial but gained enough popularity during the 1990s to be considered majority opinion. That agrees with metrical evidence in the Iliad that the name ᾽Ιλιον (Ilion) for Troy was formerly Ϝιλιον (Wilion) with a digamma.[note 3]

The language culture of Troy[edit]

From the beginning of the archaeology, the question of what language was spoken by the Trojans was prominent. Various proposals were made, but they remained pure speculation. No evidence seemed to have survived whatever. That they might be Greek was considered. However, if they were, the question of why they were not in the Achaean domain, but were opposed to the Achaeans, was an even greater mystery. Passages from the Iliad suggested that, not only were the Trojans not Greek, but the army defending Troy was composed of different language speakers arrayed by nationality.[123]

Finally in the middle of the 20th century Linear B was deciphered and a large number of documentary tablets were able to be read. The language is an early dialect of Greek, even earlier than the Homeric dialect. Many Greek words were in the early stage of formation. The digamma abounds. Linear B tablets have been found at the major centers of the Achaean domain. None, however, come from Troy.

The documents in Linear B basically inventory the assets of Mycenaean palace-states: foods, textiles, ceramics, weapons, lands, and above all manpower, especially people held in some sort of servitude. Civilizations of the times were slave societies. The terms of servitude, however, varied widely. A study by Efkleidou in 2004 detailed the types of servitude mentioned in the Linear B tablets. To her way of thinking, the main elements of servitude are that servants are outsiders, not part of the customary social structure, and that they are coerced into their positions. Someone has authority over them, whom she calls a “superior,” designated in Greek by the genitive case: “servant of ….” One of the categories of Mycenaean servant is the do-er-o (masc) and do-er-a (fem), Greek doulos, pl douloi, and doula, pl doulai.[124] A specific type of doulos is the te-o-jo do-er-o, theoio doulos, “servant of God,” a temple assistant of some sort, whose superior was the deity. These two categories were not badly off, being palace artisans, and receiving land for their services. In addition were the ra-wi-ja-ja, the lawiaiai, “captives.” These were kept in groups and performed what would be termed today “factory work.” The tablets, being ephemeral in nature, do not always classify these types, but they are detectable from the naming conventions, or lack of them, and the type of work. Efkleidou uses the term “dependent.” In all she tallied 5233 dependents in the tablets.